Highlights

- To understand how genetics can affect disease, Dr. Rana Dajani leads a research team in studying two populations in Jordan whose genetic pool has remained the same over time: the Circassians and the Chechans.

- Dr. Dajani and her team of researchers are studying genetic risk factors for diabetes in these populations. They found that diabetic participants had a genetic variation of one gene, the AKNAD1 gene. Non-diabetic participants did not have this genetic variation. Experiments are underway to determine the effect of this risk factor on diabetes.

- To help women scientists, Dr. Dajani has created a mentoring program called Three Circles of Alemat and a mentoring toolkit for use around the world. Dr. Dajani is also the founder of We Love Reading, a widely acclaimed initiative to increase literacy and reading across the world.

We know so much about human genetics thanks to the human

genome project,

which mapped the entire human

genome.

The ultimate goal of this project was to identify the complete sequence of the approximately 20,000-25,000 genes in the human body. To do this, scientists had to begin reading the genetic code, which is “written” with a type of molecule called a

nucleotide.

Nucleotides are composed of a sugar, a

phosphate,

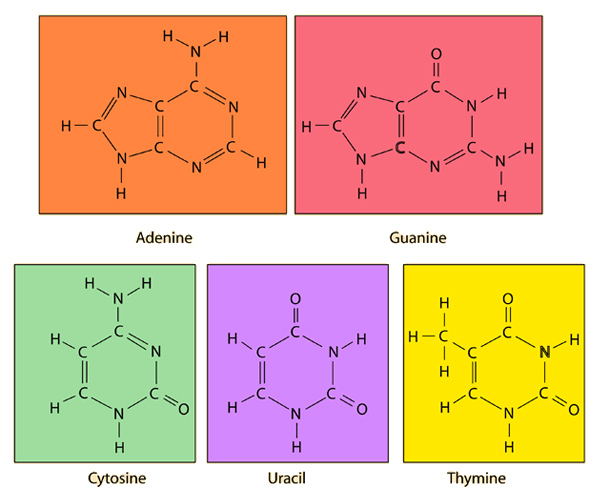

and a nitrogen-containing base. The composition of the nitrogen-containing base of the nucleotide varies, resulting in distinct molecules. The four nucleotides that form the basis of DNA are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T).

Figure 1. Nitrogenous Bases.

The human genome project sought to identify the sequences of A, C, G, and T that form the human genome, a total of about 3 billion nucleotides.

Understanding the functions of genes and proteins that make up our body is one way to develop new methods for treating and preventing diseases. For example, a single gene can have multiple variants, called

genetic variants.

Genetic variants can occur when one single nucleotide of a gene —letter in the code—is altered.

Many times, genetic variants have no impact on a person’s ability to function. However, it is possible that a single change in a gene can alter a person’s life. Examples are people born with

cystic fibrosis

or

sickle cell anemia.

And then there is a large grey area where changes in specific genes might increase or decrease the risk of a certain disease, in conjunction with other genetic and environmental factors. These changes are known as

genetic risk factors.

One disease that involves both genetic and environmental factors is

diabetes.

Diabetes is characterized by the body’s inability to properly regulate blood sugar. The organ that plays the largest role in the regulation of blood sugar is called the

pancreas,

which produces the hormone

insulin.

Insulin allows cells to take up sugar from the blood. If the pancreas doesn’t work properly, or if the proteins that allow insulin to function don’t work properly, diabetes may result.

There are several known risk factors for the development of diabetes. For example, obesity and high blood sugar have been shown to increase the likelihood that someone will develop diabetes. There are also genetic risk factors for the development of diabetes. Understanding these genetic risk factors can lead to better treatments for the disease.

One way to identify genetic risk factors is to study populations whose genetic pool has remained the same over time, without intermixing with other populations. In

Jordan,

there are two such populations: the Circassians and the Chechans. The Circassians and Chechans have lived in Jordan for about 150 years. They arrived in Jordan after fleeing their homes in southern Russia and the

Caucusus mountains

because of religious persecution. Since their arrival in Jordan, the two populations have retained their ancient cultures and lifestyles, and they have remained genetically distinct by marrying only within their ethnic groups.

Figure 2A. Circassian men

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

Figure 2B. Chechan men.

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

Dr. Rana Dajani, a geneticist interested in population health, has devoted her career to working with the Circassian and Chechan populations in Jordan to better understand how genetics can affect disease. Dr. Dajani began this multi-faceted lifetime project by developing a team of scientists that included researchers from the Circassian and Chechan communities in Jordan. Her team decided to focus on diabetes because the genetic factors for this disease are relatively unknown, and it is a disease that lacks stigma, so participants would not be afraid or ashamed to be involved. This research was intended to be collaborative with the community, so it was important that members of each community were involved from the beginning of the project.

At the beginning of the project, Dr. Dajani and her research team went to the Circassian and Chechan communities and recruited participants through community-based organizations. They explained how creating a genetic profile of each population could contribute to new understanding of diseases that affect the population. This process gained the researchers the respect and trust of each community.

To start, all participating community members met with the researchers, including a nurse and a doctor, at a local community-based organization. The doctor answered any questions the participants had about their health. Participants were told they could ask additional questions at any time.

Participants filled out a survey asking about their parents and grandparents to confirm their genetic background was part of the isolated gene pool of either the Circassian or Chechan populations. The researchers took physical measurements of each participant, including height and weight, and measurements of facial structures like the nose and cheekbones. Participants completed an additional survey about their lifestyle and habits, including their diet, exercise, medical history, and family history of disease. Lastly, researchers took a blood sample from each participant.

The blood samples were used for DNA identification of each participant’s genetic make-up and were analyzed for basic functions including fats, cholesterol, and vitamin D. These results were explained to each individual, so they would understand the results of their blood tests.

Using the DNA samples collected from the Circassian and Chechan populations, Dr. Dajani and her team created a genetic profile of each population. The researchers wanted to know whether these two genetically isolated populations had specific genetic changes that might increase or decrease their risk of developing diabetes. Dr. Dajani and her team used cutting-edge scientific technology to determine if there were differences in the genetic profiles between participants with and without diabetes. These differences could indicate genetic risk factors for the disease.

Dr. Dajani and her team found many risk factors that had already been identified by researchers. There was one new risk factor, however. The genetic difference was located on the AKNAD1 gene—diabetic participants had a genetic variation of this gene that non-diabetic participants did not have. But there was no information in the scientific literature about the function of this gene.

To find out more about the role of the AKNAD1 gene, the researchers took additional blood samples from diabetic patients and sent these cells to their collaborators at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where researchers had the technology to better understand cell function. Using this technology, Dr. Dajani’s collaborators took blood cells from diabetic participants and changed them into pancreatic cells through a new technology called

induced pluripotent stem cells.

Diabetes involves the destruction of insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, so this allowed the researchers to observe the difference between the pancreatic cells of diabetic versus non-diabetic participants in the study.

The researchers are waiting for the results of this study, but Dr. Dajani hopes that the results will add to the scientific puzzle about the development and treatment of diabetes.

In future experiments, Dr. Dajani plans to compare the genetic profiles of the Circassian and Chechan populations in Jordan to the genetic profiles of Circassian and Chechan peoples in their home environment in southern Russia. “This is a beautiful natural experiment,” explains Dr. Dajani. The Circassian and Chechan populations in Jordan left Russia 150 years ago, which is not enough time to alter their genetic profiles. However, the two populations are living in very different environments. Dr. Dajani continues, “This research will help us understand how genes and the environment work together to influence health and disease.”

Dr. Rana Dajani is an Associate Professor of Biology and Biotechnology at the Hashemite University in Jordan. Her laboratory is the world’s leading expert on the genetics of the Circassian and Chechan ethnic populations in Jordan. Dr. Dajani’s collaborative style is unique in the Arab world.

To help other women in academia, Dr. Dajani created the Three Circles of Alemat mentoring program. The goal of the program is to create circles of mentoring and social networks that promote the professional and personal lives of women.

Figure 3. Three Circles of Alemat Mentoring network.

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

The Three Circles of Alemat program was started in Jordan, but a toolkit is available to support women in academia around the world. In 2017, Dr. Dajani was awarded the IIE Global Change Maker award for this mentoring program.

Figure 4. Three Circles of Alemat participants.

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

Dr. Dajani is also the Founder and Director of We Love Reading, a widely acclaimed initiative to increase literacy and reading across the world. We Love Reading trains adults how to read aloud to children and produces children’s books that can be read aloud.

Figure 5A. We Love Reading training of adults.

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

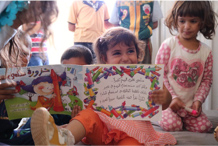

Figure 5B. We Love Reading training of adults.

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

Over the past ten years, We Love Reading has become incredibly successful, spreading to over 46 countries around the world. This program has won multiple prizes including the UNESCO International Literacy Prize.

Figure 6. Dr. Dajani receiving the UNESCO International Literacy Prize 2017.

[Source: Dr. Raja Dajani]

We Love Reading has had impacts on children and their families. Dr. Dajani formed a team of social science researchers from local universities in Jordan and from major universities in the United States including Brown University, Yale University, Harvard University, and the University of Chicago to evaluate the program. These researchers have studied the impact of We Love Reading on children’s literacy, mental health, and social empathy.

Figure 7. Refugee children attending We Love Reading Read aloud circle.

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

The results indicate that We Love Reading increases children’s reading practices and attitudes towards reading; increases children’s empathy when they read books about empathy; changes their behavior towards resources and the environment when reading books about the environment; increases mental cognition, executive function, and pre-literacy skills; and improves interactions between children and parents.

Figure 8. We Love Reading aloud circle.

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

The impacts of We Love Reading are not limited to children. Adults who participated in the program developed agency and independence and became leaders in their communities. Dr. Dajani concludes: “My goal in all my work, in and outside the scientific laboratory, is to help the world. One way to do that is through improving our understanding of disease. Another way to do that is by helping children grow up to be critical thinkers and make the world a better place.”

Figure 9. We Love Reading in Uganda.

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

Dr. Dajani is also the author of the book Five Scarves: Doing the Impossible — If We Can Reverse Cell Fate, Why Can’t We Redefine Success?

Figure 10. Cover of Dr. Dajani’s book, Five Scarves

[Source: Dr. Rana Dajani]

For More Information:

- Damgaard, P. et al. 2018. “137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes.” Nature, 557: 369-374.

- de Barros Damgaard, P. 2018. “Author Correction: 137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes.” Nature, Aug 30.

- Why the right questions make the biggest impact. Nature Middle East 2018. https://www.natureasia.com/en/nmiddleeast/article/10.1038/nmiddleeast.2018.88

- CNV Analysis Associates AKNAD1 with Type-2 Diabetes in Jordan Subpopulations.” Scientific Reports 5 (August 21, 2015): 13391. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13391.

- Al-Eitan, L.N. et al. 2017. “Diabetes mellitus in two genetically distinct populations in Jordan. A Comparison between Arabs and Circassians/Chechens Living with Diabetes.” Saudi Med J. 38: 163-169.

To Learn More:

Professor Dajani

- Stories by Professor Dajani on science and the Middle East. https://www.nature.com/search?q=rana+dajani

- Q & A: Let’s First Ask What Women Scientists Want. https://www.scidev.net/global/role-models/role-models/what-women-scientists-want.html

- A Fresh Look at Gender Equality—A Review of Dr. Dajani’s book. https://www.natureasia.com/en/nmiddleeast/article/10.1038/nmiddleeast.2018.64

- Five Scarves: Doing the Impossible — If We Can Reverse Cell Fate, Why Can’t We Redefine Success? https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05891-7

Genetics and Diabetes

- The Genome Project. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/hgp/goals

- American Diabetes Association. http://www.diabetes.org/

Literacy

- We Love Reading.http://www.welovereading.org/en/about

- https://www.promisingpractices.online/we-love-reading/

- https://ssir.org/articles/entry/1001_story_times

- http://www.fletcherforum.org/home/2018/1/6/we-love-reading-creating-brighter-lives-for-syrian-refugee-children

Mentoring

- Three Circles of Alemat mentoring program. https://tca.jssr.jo/

- Mentoring: A Powerful Tool. http://blogs.nature.com/naturejobs/2017/09/29/mentoring-a-powerful-tool/

- Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research (PEER) science: Three Circles of Alemat: creating collaborative multicultural networks for women in the sciences http://sites.nationalacademies.org/pga/peer/peerscience/pga_152063

Related What A Year Stories

- Disappearing diabetes.http://www.whatayear.org/09_17.php

- Sugar High.http://www.whatayear.org/04_09.html

- Honey I Shrank the Sensor.http://whatayear.org/09_09.html

- Get Up and Move.http://whatayear.org/05_07.html

- Early Detection Saves Lives.http://whatayear.org/04_16.php

- Microscopic Magnets.http://whatayear.org/05_15.php

- Let’s Get Specific.http://whatayear.org/01_12.php

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |