In the September story “The Dangers of Doomscrolling,” What A Year! shared about research into the potentially negative consequences of doomscrolling on social media. This month, we continue the focus on digital habits, highlighting research into the impacts of screen use on young people’s sleep.

Figure 1.

Developing healthy digital habits is important for our health and wellbeing.

[Source: Dr. Brosnan, Screenwise]

Researchers, educators, and parents have been interested in the impact of screen time on young people’s sleep habits for many years. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement on “Media and Young Minds” from 2016 recommends avoiding screen use in the hour before bed. This policy was reaffirmed in 2022. You may have already had discussions about screen use before bed in your own family.

“We think it’s time to re-evaluate these guidelines based on updated methods,” commented Dr. Rachael Taylor, Research Professor at the University of Otago in New Zealand. Dr. Taylor, together with former PhD student Dr. Bradley Brosnan, developed a new data collection method that more accurately captures young people’s screen use before and while in bed. They hope the results of this and future research will allow young people and their families to make more informed decisions about healthy screen use.

Reviewing Previous Research

Dr. Brosnan, a dietitian with clinical experience in hospitals, became interested in sleep because it was often overlooked. “I wanted to explore how we can support young people in developing healthy sleep habits to prevent long-term health issues,” recalled Dr. Brosnan. In previous research, Dr. Taylor and her team showed that early advice to promote good sleep health could reduce obesity in children up to five years of age. These results led Dr. Taylor, a child obesity researcher, to focus on improving sleep in young people. At the time, screen use was considered a major contributor to poor sleep for children and adolescents.

As Dr. Brosnan reviewed the literature on screen use and sleep as part of his PhD research, he soon encountered a problem. The ways that screen use had been measured previously were likely not accurate enough. The body of research that supports young people avoiding screen use before bed was predominantly conducted using self-reported data in the form of questionnaires. Young people or their parents were asked general questions about a young person’s “usual screen use time” and “average number of hours of sleep.” Analyzing this data showed a correlation between screen use before bedtime and fewer hours of sleep, leading to the AAP recommendations.

However, Dr. Brosnan and Dr. Taylor noticed multiple gaps in the research. For example, the previous research did not distinguish between different activities available on screens (social media use vs YouTube vs texting) or the kinds of content being viewed. In addition, technology advances at a much faster pace than research, meaning that studies conducted even a few years ago are probably not a true reflection of how screens are being used by young people today. “We think it is unlikely that a paper questionnaire accurately captures what young people are doing on screens,” added Dr. Taylor.

The researchers realized that they would first have to develop a method to more accurately measure screen use before he could study the impacts of screen use on sleep.

Measuring Screen Use

When Dr. Brosnan began this project, a method for collecting and measuring screen use using video cameras did not exist. Together with his team, he had to develop this method from scratch. The researchers experimented with setting up video cameras in young people’s homes and observing what happened. They gathered many hours of data on screen use from 15 volunteers aged 10 to 14 years and their families.

Each participant was given a wearable camera, the Patrol Eyes SDV video camera, that rested on their chest looking outward to capture exactly what they were doing on their device. A stationary camera was set up to the side of the bed to monitor screen use once the participant was in bed.

Figure 2.

Patrol Eyes SDV video camera (left), wearable harness set-up (center), and stationary set-up (right).

[Source: Dr. Brosnan]

Some of the video footage included unstructured time, where participants used their phones as they would normally. The researchers also captured some structured time, where participants were instructed to do a specific activity on their phones for a given amount of time.

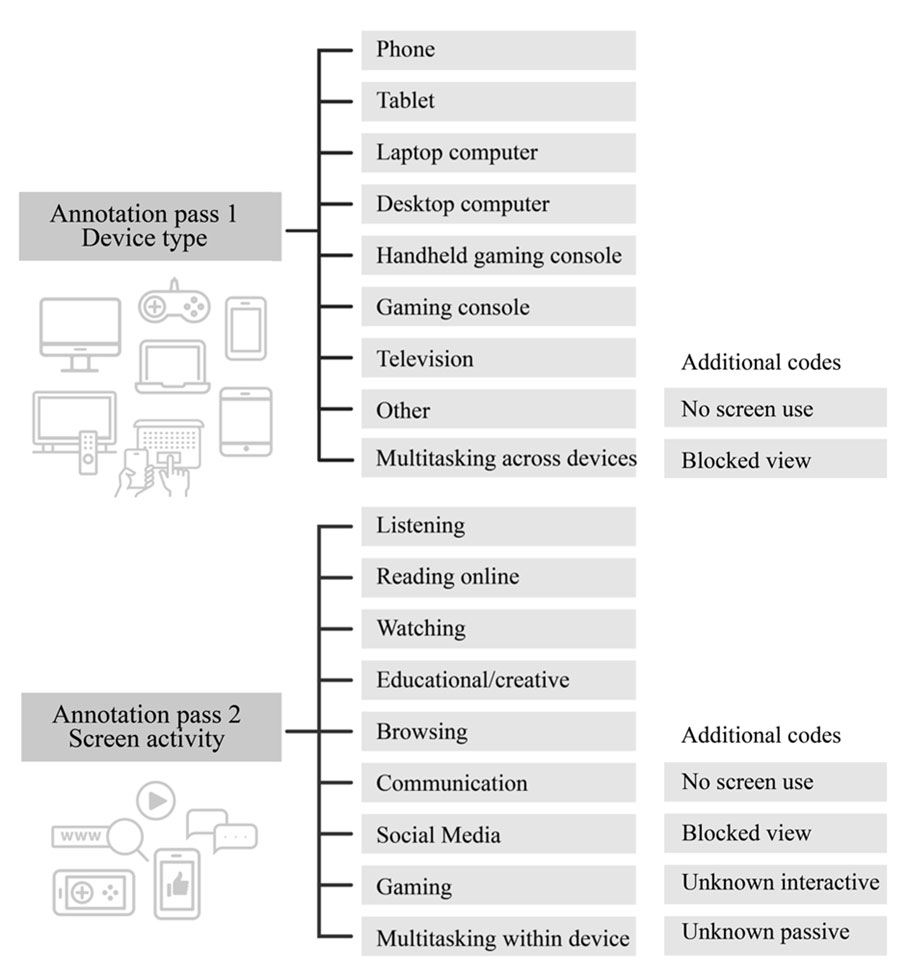

As Dr. Brosnan and Shay-Ruby Wickham, a graduate student in Dr. Taylor’s lab, viewed the video footage, their task was to develop systematic ways to describe, or code, what participants were doing on their screens. The researchers made decisions about how they would code what they were seeing such that the data could be analyzed in the future.

Figure 3.

Dr. Brosnan and Shay-Ruby Wickham with the Patrol Eyes SDV wearable video camera used in this study.

[Source: Dr. Brosnan]

“We definitely hit some challenges along the way,” recalled Dr. Brosnan. For example, if a participant was scrolling on social media and paused scrolling to watch a video, did that count as social media use or watching a video? They decided that video content on social media would count as social media use if the video was under five minutes and watching a video if it was over five minutes.

By the end of the development process, the researchers had created a method for coding video data based on what device(s) the participant was using and what activity they were doing. Devices included phones, tablets, laptop computers, desktop computers, gaming consoles, and televisions.

Activities included:

- Listening to audio, such as music or audiobooks, without touching the screen

- Reading a book, comic, or graphic novel

- Watching TV, movies, or other video content

- Educational or creative content such as homework, spelling games, learning math or a language online, and creating art or music online

- Browsing websites or searching for what to watch

- Communication using text, email, or messaging apps

- Social media use such as Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok

- Gaming or watching someone else gaming

- Multitasking by engaging in two or more activities at the same time on the same device or different devices

Figure 4.

An overview of the full screen use coding protocol Dr. Brosnan and colleagues developed.

[Source: Dr. Brosnan]

The researchers grouped these activities into two broad categories: passive and interactive. Passive activities included watching, listening, reading, and browsing. Interactive activities included gaming, communication, educational or creative tasks, and multitasking. Social media was left as its own category because it includes a mix of both passive and interactive tasks.

The researchers revised their model through testing with video footage from additional participants. They also wanted to make sure that their coding system could be understood more broadly. To do this, they trained additional research assistants in the system and analyzed the coding results to make sure that different researchers would code the data the same way. “This part of the project was really important to ensure the reliability of our results,” added Dr. Taylor.

Testing the Relationship Between Screen Use and Sleep

With a method for capturing and coding screen use data in real time, the researchers could now apply it to better understand the relationship between screen use and sleep in a project called the Bedtime Electronic Devices study. This study included 85 young people aged 10 to 14 years who recorded themselves for three weekday nights and one weekend night over eight days. The research team came to participants’ homes at the start of the study and continued to visit to make sure everything was going smoothly. Sleep was measured using video footage and a device participants wore on their wrists 24 hours per day for eight days.

Once the footage was collected, Dr. Brosnan and other researchers used their coding system to code the data for statistical analysis. This analysis showed that screen use in the two hours before bedtime had no impact on sleep duration or the time it took to fall asleep. However, the researchers found that screen use greatly impacted sleep when young people brought devices into the bedroom. “There was a direct tradeoff between time spent on screens while in bed and sleep loss,” explained Dr. Brosnan. For example, if a participant spent 30 minutes on social media or another interactive activity in bed, they lost almost 30 minutes of sleep. This was also true for passive activities like reading or watching a video, but to a lesser extent. Engaging in social media or interactive activities before bed also appeared to increase the amount of time it took to fall asleep once the participant put their phone away.

The results of this research reveal a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between screen use and sleep. “Screen use before bed does not appear to be the problem,” explained Dr. Brosnan. “It’s screen use in bed that we should be worried about.” The researchers believe that screen use while in bed is likely more impactful because it happens just before going to sleep.

The researchers also conclude that “screen use” is too general a term. Even in bed, not all screen use is the same. Passively receiving information, like listening to music or watching a video, will impact your sleep less than interactive activities such as social media or messaging apps.

Dr. Brosnan and Dr. Taylor hope that these findings can be helpful to parents and young people, potentially reducing family conflicts around screen use. “It’s important to be aware of how and when you’re using your phone,” Dr. Brosnan added. “Once you’re in bed, try to avoid apps and activities designed to keep you engaged and on your device longer, such as scrolling or auto-playing videos or episodes.”

In his ongoing work, Dr. Brosnan hopes to integrate these research findings into his health and nutrition practice. Together with his wife, he has founded a platform called Screenwise to educate parents, family, and the public about creating healthier screen use, protecting sleep, and improving well-being. Screenwise provides practical strategies for managing screen time in today’s digital world.

Dr. Taylor is planning several experiments to follow up on this research. “So far, our research has been observational,” she explained. This means that the researchers are only observing what young people are doing on their screens and reporting what they observe. “Now we are moving towards experimental research,” added Dr. Taylor. In these experiments, Dr. Taylor will take what she and her team have learned in their observational studies to design experiments with different conditions. For example, some participants may be asked to modify their screen use in certain ways, allowing the researchers to compare the sleep habits of young people in the experimental and control conditions.

Dr. Taylor and Dr. Brosnan are also looking forward to additional results from this research project. In addition to measuring screen use and sleep, the researchers also asked about other factors involved in a healthy lifestyle, such as diet and exercise. In future work, they hope to learn what this data reveals about the relationship between nutrition, exercise, sleep, and screen use and how they affect young peoples’ health.

Dr. Bradley Brosnan completed his PhD work in 2023. He is the founder of Screenwise, an educational platform that uses research to help families and communities develop better digital habits. When not at work, Dr. Brosnan enjoys gardening, skiing, biking, tennis, and spending time with his family.

Dr. Rachael Taylor is Research Professor, Head of Department and Karitane Fellow in Early Childhood Obesity at the University of Otago in New Zealand. Her research focuses on how sleep, diet, and exercise impact obesity in children. When not involved in research, Dr. Taylor enjoys spending time outdoors, gardening, cooking, and sewing.

For More Information:

- Brosnan B, et al. Screen Use at Bedtime and Sleep Duration and Quality Among Youths. JAMA Pediatr. Published online September 3, 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39226046/

- Brosnan B, et al. Development of a Protocol for Objectively Measuring Digital Device Use in Youth. Am J Prev Med. 2023;65(5):923-931. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37156402/

To Learn More:

- Screenwise. https://www.screenwise.co.nz/

- American Academy of Pediatrics. “Media and Young Minds.” https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/138/5/e20162591/60503/Media-and-Young-Minds

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com