Charles Darwin was an English naturalist and explorer in the 1800s well known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. Darwin also wrote extensively about human emotions, devoting an entire chapter of his 1872 work The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals to the subject of blushing. “Blushing,” wrote Darwin, “is the most peculiar and the most human of all expressions.” He theorized that blushing occurs when we think about how others think about us, what social psychologists1 now call mentalization.2 Unlike other Darwinian theories like the theory of natural selection,3 Darwin’s hypothesis about blushing had never been tested—until now. New research by Dr. Milica Nikolić and colleagues at the University of Amsterdam and the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience in the Netherlands and D’Annunzio University of Chieti in Italy shows that Darwin was not totally right. While blushing may be “the most human” of all expressions, it may require little mentalizing because it is actually an automatic process driven by the most basic parts of our brain.

Social Anxiety and Blushing

Dr. Milica Nikolić is a developmental psychologist who began her research career by investigating how social anxiety disorders4 develop in young children. According to the American Psychological Association, social anxiety is characterized by a fear of social situations such as meeting new people and making conversation that might be embarrassing or cause someone else to think negatively about you. While many young people may feel shy or anxious sometimes, ongoing fear or worry that prevents you from living a normal life is considered a social anxiety disorder that can get better with proper treatment.

Dr. Nikolić became interested in blushing as a topic of research because it’s a hallmark physical symptom of social anxiety. Although there are multiple theories for why we blush, such as Darwin’s hypothesis of mentalizing, no research had been published on the subject. Dr. Nikolić set out to design an experiment that could uncover what happens in the brain when we blush.

Dr. Nikolić knew that the study would involve imaging of the brain using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a noninvasive technique for visualizing brain activity.

Figure 1

A patient entering an MRI machine.

[Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:MRI_machine_with_patient_(23423505123).jpg]

She chose to focus this experiment on adolescent girls because this population is known to be highly sensitive to the opinions of others, and Dr. Nikolić thought they would be more likely to blush under experimental conditions. “Our biggest challenge was to figure out how to induce blushing in an MRI scanner,” explained Dr. Nikolić. “Blushing is a social phenomenon, and in an MRI scanner participants are alone.” To address this challenge, Dr. Nikolić and colleagues designed a protocol that involved singing difficult songs and then watching yourself singing the songs in the scanner.

Experimentally Inducing Blushing

Dr. Nikolić recruited adolescent girls in Amsterdam aged 16-20 years old to participate in the study. To reduce bias, potential volunteers were told they would participate in a social task and watch videos in an MRI scanner. Dr. Nikolić did not share details about the social task because she did not want potential volunteers to choose not to participate based on worry or anxiety about singing. All potential volunteers were given a questionnaire about social anxiety, and those scoring high or low on the survey were invited to participate. A total of 40 volunteers completed all the tasks associated with the study.

Study volunteers were asked to make two visits to the Behavioural Science Laboratory at the University of Amsterdam. During the first visit, participants were filmed singing karaoke to four songs:

- “Hello” by Adele

- “Let it go” from Frozen

- “All I want for Christmas is you” by Mariah Kerry

- “All the things you said” by tATu

These songs were chosen because they were both familiar and difficult to sing. Familiarity with the tune ensured that participants would be able to complete the karaoke task, and difficulty singing increased the possibility that participants would be embarrassed when watching themselves in the second part of the study. The researchers edited the karaoke footage into 15 clips lasting 24 seconds each that highlighted the most difficult parts of each song.

During the second study visit, participants watched karaoke footage of themselves as well as other participants while in the MRI scanner. Researchers placed a thermometer on participants’ left cheek to measure cheek temperature throughout the experiment. An increase in cheek temperature is a physical sign of blushing, which allowed the researchers to correlate the time of blushing with the brain activity they saw.

The experimental procedure in the MRI scanner included three sessions of five trials. In each trial, participants were shown the same video clip sung three times: once by the participant (self-viewing condition), once by a fellow volunteer (other-viewing condition), and once by a professional who was falsely introduced as yet another participant of the study (professional viewing condition). The order of video clips shown was randomized by computer. Participants were given a 12 second break between trials.

The self-viewing condition was the experimental condition. To heighten embarrassment in this condition, the researchers told participants that other volunteers were watching their video clips at the same time.

The other-viewing and professional-viewing conditions represent two layers of controls to ensure that the blushing participants experienced was due to their embarrassment at watching their own videos. In the first layer of control, the other-viewing condition, participants were shown the exact same video clips but sung by another volunteer who was judged to have similar singing ability by independent raters. This was to separate blushing from bad singing in general compared to blushing from watching yourself sing.

However, even with this layer of control, there was still the possibility that participants might blush from vicarious embarrassment. In other words, a participant watching someone else’s videos might feel embarrassed and blush on behalf of the other person. To control for this, the researchers introduced a second layer of control, the professional-viewing condition, in which participants were shown the same 15 video clips sung by a professional singer who had been invited to record the four songs specifically for this experiment.

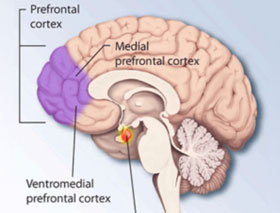

It was important for the researchers to control for the cause of blushing because they were interested in which areas of the brain were involved. It was likely that blushing for different reasons would activate distinct brain regions. Specifically, the researchers wanted to identify whether blushing was due to mentalizing—thinking about what others think of us—as Darwin said, or whether it was a more automatic process. If mentalizing was involved, the researchers would expect to see activity in the medial prefrontal cortex5, the newest, uniquely human part of our brain involved in complex, abstract thought.

Figure 2

Areas of the prefrontal cortex, in purple, including the medial prefrontal cortex.

[Source: National Institute of Mental Health]

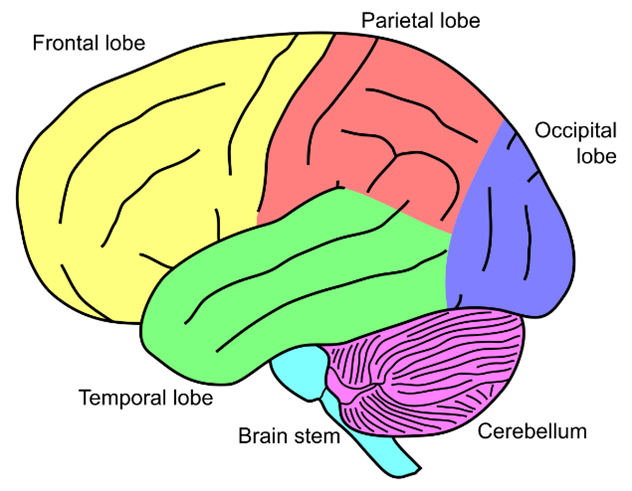

On the other hand, if blushing was a more automatic process, the researchers hypothesized that other areas of the brain responsible for emotional arousal, such as parts of the cerebellum6 and brain stem7, would be activated.

Figure 3

Areas of the brain including the cerebellum (purple) and brain stem (light blue).

[Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerebellum]

Across all three sessions, the researchers captured brain activity as participants watched the karaoke footage and correlated this activity with blushing as measured by the thermometer on participants’ left cheek. Once all participants had completed both laboratory visits, the researchers analyzed the results.

Results and Future Work

The results showed a significant increase in blushing in the self-viewing condition compared with either the other-viewing or professional-viewing conditions.

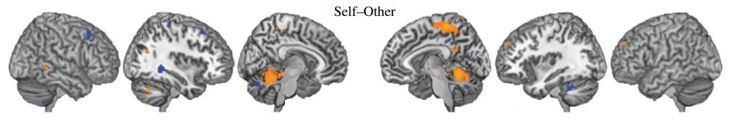

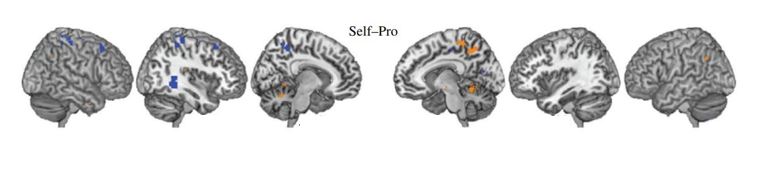

Figure 4

Comparison of brain areas activated in the self-viewing and other-viewing conditions. The orange represents areas that were activated with more blushing in the self-viewing condition compared to the other-viewing condition.

[Source: Nikolić et al 2024, Fig 3c]

Figure 5

Comparison of brain areas activated in the self-viewing and professional-viewing conditions. The orange represents areas that were activated with more blushing in the self-viewing condition compared to the professional-viewing condition.

[Source: Nikolić et al 2024, Fig 3d]

The fMRI imaging showed the highest brain activity while blushing in the cerebellum and minimal brain activity in the medial prefrontal cortex. “This tells us that blushing may not require mentalizing—it seems to be a more automatic process,” explained Dr. Nikolić.

Based on these results, Dr. Nikolić believes that blushing indicates attention and an emotional response.

Dr. Nikolić added that there are ways to experimentally induce embarrassment that may be accompanied by blushing that require more cognitive processing, like asking participants to remember a situation when they felt embarrassed. In these cases, researchers have noted more activity in the medial prefrontal cortex with more embarrassment than the present study. However, Dr. Nikolić’s research shows that cognitive processing is not a necessary condition for blushing.

Although this research did not find evidence for Darwin’s theory of blushing as mentalizing, Dr. Nikolić does agree with Darwin that blushing is a common human experience. In this study, the researchers did not find a correlation between social anxiety and blushing. “This may mean that blushing is a common response to this kind of task, where all participants, no matter their anxiety, might feel exposed watching themselves sing,” explained Dr. Nikolić. “People with social anxiety might experience embarrassment and blush in many different situations, but watching yourself sing is an embarrassing situation many people can relate to.”

In future work, Dr. Nikolić plans to continue to investigate when blushing emerges in human development. Given that the findings of this study suggest that complex cognitive processes may not be necessary for blushing to occur, we would like to see whether young children, or even babies, would be able to blush.

Dr. Nikolić emphasized that this was a collaborative research project that involved a multidisciplinary team of researchers including social psychologists, developmental psychologists8, and neuroscientists9 who assisted with the design of the study and data analysis.

Dr. Milica Nikolić is Assistant Professor of Developmental Psychopathology10 at the Research Institute of Child Development and Education at the University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. Her research focuses on understanding how young children develop the skills and capabilities to navigate the social world. When not in the laboratory, Dr. Nikolić enjoys outdoor activities, traveling, and spending time with her family.

For More Information:

- Nikolić, M., et al. 2024. “The blushing brain: neural substrates of cheek temperature increase in response to self-observation.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 291: 20240958. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2024.0958

To Learn More:

- “Social Anxiety Disorder: More Than Just Shyness.” National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/social-anxiety-disorder-more-than-just-shyness

- “What is Social Anxiety?” Child Mind Institute. https://childmind.org/article/what-is-social-anxiety/

- Harris, Nicole. “How to Help Kids Deal with Social Anxiety.” Published August 15, 2023. https://www.parents.com/kids/health/childrens-mental-health/how-to-help-kids-deal-with-social-anxiety/

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com