As a child, Teddy recalled that his mother used to give him a cup of strong coffee in the morning for breakfast. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children under 12 not consume any caffeine, and those 12-18 consume a maximum of 100 mg (about two cans of soda) per day. But this was the 1860s. Teddy had asthma, and coffee was a known remedy that could help improve breathing in people with the condition. Teddy, born Theodore Roosevelt, would go on to become the 26th president of the United States. He is the only president to date who had asthma.

Asthma1 is a chronic respiratory disease that leads to inflammation and narrowing of the airways. It is the most common chronic respiratory disease in the US and around the world, affecting nearly 300 million people globally, including 4.5 million children in the United States. Asthma is the number one cause of school absences in children and work absences by those who take care of children in the US.

Fortunately, asthma treatment has greatly improved since the days of President Roosevelt. But there is still so much more that scientists and doctors don’t yet understand about asthma. New research by Dr. Juan Celedón, Professor of Medicine, Epidemiology2, and Human Genetics at the University of Pittsburgh and Division Chief of Pulmonary Medicine at the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, PA, and colleagues has identified three distinct subtypes of asthma in children. Dr. Celedón hopes this research will improve treatment of childhood asthma by enabling patients to be matched to specific treatments based on subtype.

Types of Asthma

Asthma is a condition that affects the airways and lungs. Symptoms of asthma include wheezing, getting out of breath, tightening of the chest, and coughing. People with asthma may experience asthma attacks3, a rapid worsening of symptoms that occur when something triggers the lungs, increasing inflammation4 and causing the airways to narrow. This restricts movement of air in and out of the lungs and can make it hard to breathe. An asthma attack can be a serious medical emergency, and asthma is a leading cause of visits to the emergency room and stays in the hospital.

There are several types of asthma that are distinguished based on our understanding of what triggers the disease. These include:

- Allergic asthma – caused by triggers5 that also cause allergies6 including dust, mold, pollen, and pets

- Non-allergic asthma – caused by triggers that are not associated with allergies including air pollution, respiratory infections like a cold, the flu, or COVID-19, cigarette smoke, breathing cold air, or certain medicines

- Exercise-induced asthma – triggered by exercise, especially when the air is dry

- Obesity-related asthma – related to obesity or weight gain

Asthma and Inflammation

In recent years, scientists have recognized that inflammation plays an important role in the development of asthma. Inflammation can occur whenever the body’s immune system responds to changes, such as an illness, an injury, or a foreign substance like germs. When inflammation occurs as a temporary process, it is a great way to keep us safe and healthy. But when inflammation becomes chronic, it can cause disease instead. In people with asthma, chronic inflammation of the airways causes them to narrow and makes it more difficult for air to pass through.

Figure 1.

Narrowing and inflammation of the airways during an asthma attack compared to a healthy (normal) airway.

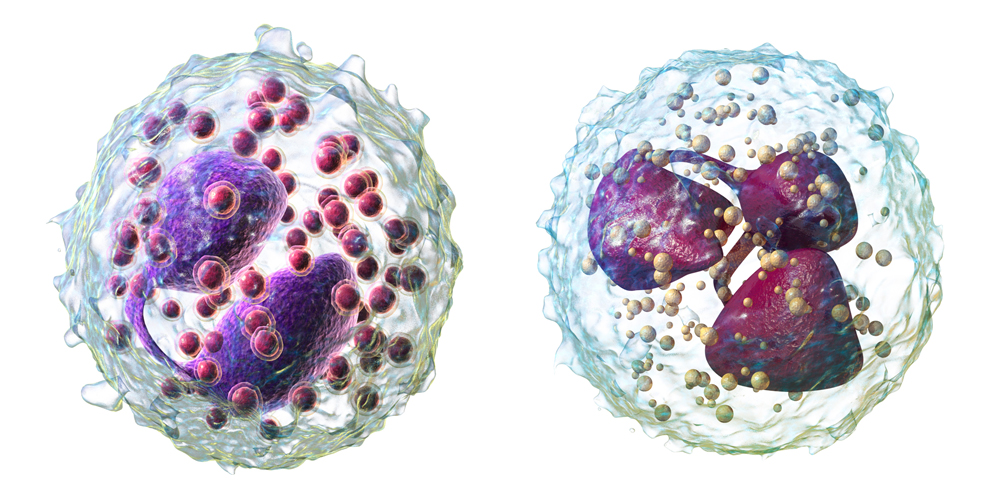

The immune system7 is made up of many different cell types that work together to produce an inflammatory response. In asthma, the inflammatory cells we know the most about are eosinophils and neutrophils. Both eosinophils8 and neutrophils9 are white blood cells 10 that fight infections and disease. Neutrophils primarily target bacteria and fungi, whereas eosinophils primarily target parasites and are involved in the body’s allergic response.

Figure 2.

Eosinophil (left) and neutrophil (right), two types of white blood cells involved in inflammation.

[Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blausen_0352_Eosinophil_(crop).png; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blausen_0676_Neutrophil_(crop).png]

Recent research has identified three subtypes of asthma that differ based on the types of immune cells involved. These include:

- T2 high – characterized by high levels of eosinophils

- T17 high – characterized by high levels of neutrophils

- T2 low/T17 low – neither eosinophils or neutrophils are found in high levels

As our understanding of asthma continues to improve, these subtypes may change.

Asthma Management

The goal of asthma management is to help control the disease to reduce symptoms and avoid asthma attacks. An important part of asthma management is knowing what triggers the disease for each individual and figuring out ways to reduce exposure to these triggers, when possible. Currently, medications to treat asthma are broadly the same no matter what type of asthma you have. Common medications include:

- Bronchodilators11, which reverse the narrowing of the airways that make it harder to breathe. Coffee can act as a mild bronchodilator, which is likely why it was considered an asthma treatment in Roosevelt’s time. Bronchodilators are typically delivered to the lungs using an inhaler.

- Corticosteroids12, which reduce inflammation. Corticosteroids are typically delivered to the lungs using an inhaler. Oral corticosteroids are sometimes used during a severe asthma attack or for people with very severe asthma.

- Biologics13, which target specific inflammatory cells that cause asthma. Biologics are only used in cases of severe asthma when previous treatments have not worked. Currently, biologics only work in people with T2 high asthma.

Asthma Research in Children

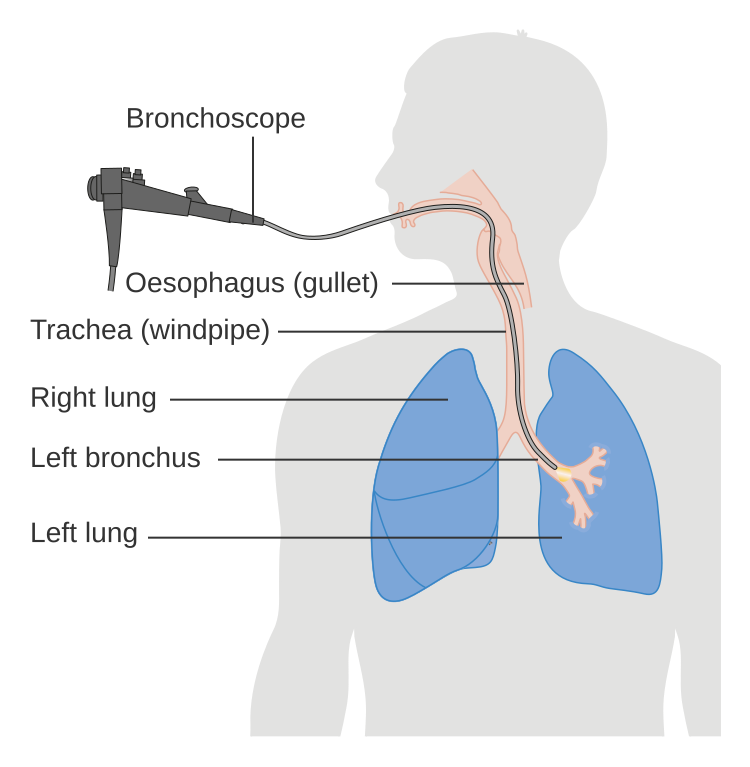

The research to identify the three known subtypes of asthma (T2 high, T17 high, and T2 low/T17 low) was conducted in adults. In these studies, adult volunteers with asthma agreed to undergo a procedure called a bronchoscopy14, where they were put under anesthesia while doctors took samples of the tissue lining their lungs. These samples were analyzed to identify different cell types in the tissues and associated genetic changes.

Figure 3.

During a bronchoscopy, doctors insert a bronchoscope into the airways to take tissue samples from the lungs.

[Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diagram_showing_a_bronchoscopy_CRUK_053.svg]

Similar research in children has been limited by the invasive nature of bronchoscopies. Children can undergo bronchoscopies when medically necessary, but they are not a good tool for research. Dr. Celedón specializes in childhood asthma research, and he wanted to develop a less invasive way to study the disease in children. He based his work on findings from colleagues showing that genetic changes in the lining of the lungs were mirrored by changes in the lining of the airways in the nose. This understanding of the relationship between the lungs and nose allowed Dr. Celedón to develop procedures to identify asthma subtypes based on genetic changes in samples of nasal tissue. These samples require only a simple nasal swab. “This is not even as invasive as the nasal swabs in COVID-19 tests that we are used to by now,” explained Dr. Celedón. “Those swabs go up much higher into the nose than what we use in our research.”

Figure 4.

Noninvasive technique to collect samples of nasal tissue.

[Source: UPMC/Pitt Health Sciences]

Dr. Celedón used this noninvasive technique in three groups of research participants for over a decade:

- Epigenetic Variation and Childhood Asthma in Puerto Rico (EVA-PR) included 1,111 children and adolescents aged 9 to 20 years from multiple cities in Puerto Rico between 2014 and 2017.

- Vitamin D Kids Asthma (VDKA) included 115 children and adolescents aged 6 to 16 years who were patients at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh between 2016 and 2019.

- Stress and Treatment Response in Puerto Rican and African American Children with Asthma (STAR) included 249 children and adolescents aged 8 to 20 years old who were patients at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Center or UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh between 2018 and 2022.

In all three studies, participants filled out questionnaires on demographic information and respiratory health, had their blood drawn, and had a nasal sample taken.

Now that these three studies have been completed, Dr. Celedón used data from 459 participants across the three studies to determine the relative proportions of the three subtypes of asthma in children. Previous researchers had identified genetic profiles for each of the subtypes of asthma in adults, which Dr. Celedón tested in children. “Our big question was whether this would work in children like it did in adults,” explained Dr. Celedón, “and it did!”

Previous studies had found that T2 high inflammation was most common in both adults and children. There are many reasons for this, including testing techniques and the relationship between asthma and allergies.

- Testing: For much of the time that these previous studies had taken place, T2 high inflammation was the only type of inflammation that could be tested for. Since there were no tests for other types of inflammation, these studies were biased15 in favor of the type of inflammation the researchers could positively identify.

- The role of allergies: Both asthma and allergies are characterized by T2 high inflammation, and many researchers in the US assumed that anyone who had asthma and at least one allergy had T2 high asthma. Studies from other parts of the world have shown that this is not necessarily the case.

The results from Dr. Celedón’s research showed that T2 high asthma was the least common subtype amongst participants. Averaged across the three cohorts, the results showed that 25.8% of participants had T2 high asthma, 39.5% had T17 high asthma, and 34.7% had T2 low/T17 low asthma. “This is an important contribution to our understanding of asthma in children,” added Dr. Celedón. These results may explain why certain treatments don’t work for some people with asthma. They may also open doors to research into new treatment options.

Asthma Health Disparities

An important aspect of Dr. Celedón’s work is understanding racial and ethnic disparities16 in asthma across the US. While asthma can affect anyone, it is a disease more commonly found in people from poorer communities and marginalized communities around the world. In the US, asthma disproportionately affects Black, Puerto Rican, Native, and multiracial children compared to White children. The vast majority of these disparities are related to inequities in environmental exposure. For example, lack of access to fruits and vegetables, fewer opportunities to exercise, indoor pollution from common allergens17 like dust, mold, and pests, and proximity to sources of outdoor air pollution like highways and factories.

Dr. Celedón has devoted much of his career to understanding health disparities in asthma and makes sure to prioritize the participation of Black and Puerto Rican children in his research. He first noticed racial and ethnic disparities in asthma while in medical school in New York City, and understanding the root causes of what he observed became a passion that has driven his career. Previous studies have shown that Black and Puerto Rican children have more severe asthma than their White counterparts. It is not yet known whether these combinations of environmental exposures lead Black and Puerto Rican children to develop different subtypes of asthma. This is one goal of Dr. Celedón’s ongoing and future work.

Future Work

While asthma management has greatly improved since the time of President Roosevelt, there is still so much more that remains unknown. Many young children under 3 years old develop asthma, but about half of children with asthma before age 3 will have grown out of it by age 6. Some children may grow out of asthma as they get older, while some will continue to have asthma for the rest of their lives. Why this happens, and whether this is specific to certain subtypes of asthma, is an important subject of future research.

It is also not known whether asthma subtypes can change over time. Dr. Celedón believes that they may be able to change because of asthma treatment or from the influence of sex hormones during puberty. He is involved in an ongoing study in older adults with Puerto Rican and Dominican heritage to start to answer that question. He is also planning studies to follow children with asthma over time, which will help improve our understanding of the relationship between asthma in children and adults.

Another area of future work is new ways of testing and treating asthma. Dr. Celedón hopes that the availability of a test using only a nasal swab to determine asthma subtype will allow for better selection of patients for clinical trials18. For example, when current treatments for people with severe T2 high asthma were first tested in patients, the trials were unsuccessful. This was because they were tested in anyone with asthma, regardless of subtype. When the trials only included people with T2 high asthma, based on indicators such as high eosinophil levels measured in the blood, they were shown to be effective. For the development of future treatments for T17 high and T2 low/T17 low asthma, it is important that clinical trials only include participants who have these subtypes of asthma. A noninvasive nasal swab that can identify asthma subtype can help ensure that happens.

Finally, current treatments for severe asthma are only available for people with the T2 high subtype. “We hope that by positively identifying additional asthma subtypes, we can encourage research into medications that target these other types of inflammation,” concluded Dr. Celedón.

Dr. Juan Celedón is Professor of Medicine, Epidemiology, and Human Genetics at the University of Pittsburgh and Division Chief of Pulmonary Medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, PA. His research seeks to understand the genetic and environmental factors associated with asthma and other respiratory diseases, with a particular focus on racial and ethnic disparities in childhood asthma. Outside of work, Dr. Celedón loves to travel. He is a member of the 50 by 50 club, a group of people who have been to all 50 states by age 50, and he has been to over 80 countries.

For More Information:

- Yue M, Gaietto K, Han YY, et al. Transcriptomic Profiles in Nasal Epithelium and Asthma Endotypes in Youth. JAMA. 2025;333(4):307-318. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.22684

To Learn More:

Childhood Asthma

- The Celedón Lab for Pediatric Asthma Research. https://www.chp.edu/research/areas/pulmonary-medicine/celedon-lab

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/index.html

- MedLine Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000990.htm

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. https://aafa.org/asthma/living-with-asthma/asthma-in-children/

- World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma

Health Disparities in Asthma

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. https://aafa.org/asthma-allergy-research/our-research/asthma-disparities-burden-on-minorities/

- U.S. Office of Minority Health. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/asthma-and-blackafrican-americans

- American Lung Association. https://www.lung.org/blog/asthma-burden-on-black-community

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com