Highlights

The Lothian Birth Cohorts of 1921 and 1936 are a rich source of data that researchers are using to better understand the aging process, including cognitive decline and dementia. These researchers used the Lothian Birth Cohort to study the connections between lifetime exposure to air pollution and cognitive decline. This was the first-time researchers have been able to create historical models to estimate the levels of air pollution in the years before air pollution data were monitored and collected. Future research into the connections between air pollution and cognitive decline will focus on improving the methods of historical modeling of air pollution and expanding the research to include several different kinds of air pollution.

Imagine that all 11-year-old children in the entire country are called to take an intelligence test on the same day. The country wants to understand the distribution of intelligence amongst its children, and almost everyone participates. This has only happened one place in the world as far as we know: in Scotland, in 1932 and 1947.

Figure 1. Map of Scotland, United Kingdom, and Europe

[Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scotland#/media/File:Scotland_in_the_UK_and_Europe.svg]

In 1932, the Scottish Council for Research in Education decided to administer an intelligence test called the

Scottish Mental Survey

to better understand the distribution of intelligence amongst Scottish children. All children who were born in 1921 sat for the same exam nationwide on June 1, 1932. A total of 87,498 children took the exam.

Figure 2. Cover of the Scottish Mental Survey as given in 1932

[Source: https://www.ed.ac.uk/lothian-birth-cohorts/history/scottish-mental-survey-1932]

Fifteen years later, concerned that the average intelligence of the next generation was dropping, Scotland called all children born in 1936 to take the same exam. This time 70,805 children participated on June 4, 1947.

Figure 3. A group of 11-year-old Scottish children who sat for the Scottish Mental Survey in 1947

[Source: https://www.ed.ac.uk/lothian-birth-cohorts/history/the-scottish-mental-survey-1947]

Both exams showed the same distribution of intelligence amongst 11-year-old Scottish children, disproving the hypothesis that overall intelligence was decreasing amongst Scottish youth. The results were filed away and forgotten for decades.

Birth of the Lothian Cohort

In the late 1990s, Scottish researchers Ian Deary and Lawrence Whalley discovered the long-forgotten data from the Scottish Mental Surveys of 1932 and 1947 in storage at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. “This was a huge treasure trove of data just waiting to be used,” commented Dr. Tom Russ, a researcher and psychiatrist at the University of Edinburgh specializing in

dementia

and

cognitive decline.

Immediately the researchers realized the rich potential of this data for understanding brain changes over time. They set out to contact all participants who were still alive and willing to engage in follow-up with the researchers.

Of the original 87,498 children who took the Scottish Mental Survey in 1932, a total of 1,091 adults agreed to participate in the research study when they were 70 years old.

Figure 4. Members of the Lothian Birth Cohort

[Source: https://www.ed.ac.uk/lothian-birth-cohorts]

This involved a complete medical exam, a series of cognitive tests including the same test taken at age 11, and questionnaires on a range of topics including personality, quality of life, and diet. This group of adults became known as the Lothian Birth Cohort of 1921, named for Lothian county surrounding the Scottish capital of Edinburgh.

Dementia and Geographical Variation

The main purpose of the long-term research project involving the Lothian Birth Cohorts of 1921 and 1936 is to better understand the factors that contribute to ‘normal’ cognitive aging as well as cognitive decline and dementia. Dementia is a class of disorders characterized by decreased cognitive function that impacts a person’s life. An estimated 47 million people across the globe were diagnosed with dementia in 2015 with approximately 10 million people newly

diagnosed each year.

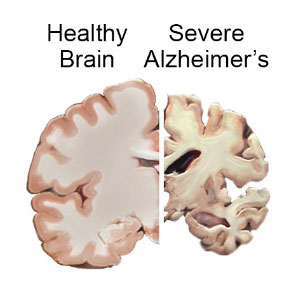

The most common form of dementia is caused by

Alzheimer’s disease,

where memory is most affected. Alzheimer’s disease affects the brain in predictable ways both in terms of symptoms and the appearance of the brain in imaging studies.

Figure 5. Normal brain compared to brain with Alzheimer’s disease

[Source: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet]

Known risk factors for the development of Alzheimer’s dementia and other forms of dementia include lower levels of schooling in early life, high blood pressure, and obesity. Research has shown that about one third of the risk for dementia is explained by these risk factors and another third by genetic risk factors. The remaining third of risk is still unknown. There is some evidence that environmental factors including exposure to air pollution over a lifetime can contribute to cognitive decline. However, this has been a difficult area to research because of poor air pollution data.

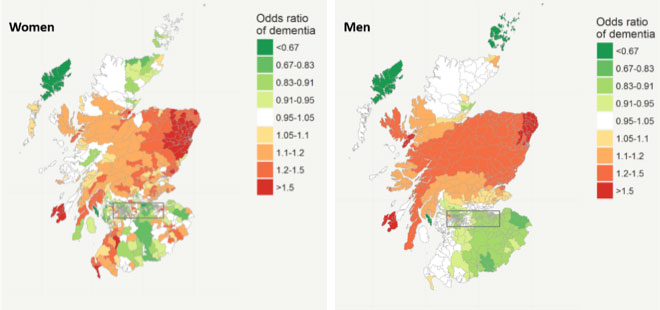

The first research involving the Lothian Birth Cohort and the Scottish Mental Survey was published in 2007. One finding to emerge from this research of particular interest to Dr. Russ was a pattern of geographical variation in dementia. People who lived in the north of Scotland had increased risk of developing dementia compared with those who lived in southern Scotland. This was a surprising finding for Dr. Russ because it was distinct from the usual geographical patterns.

Figure 6. The likelihood of developing dementia based on where you live for women and men, with green (odds ratio <1) indicating decreased risk of dementia and red (odds ratio >1) indicating increased risk of dementia

[Source: Image courtesy of Dr. Russ]

Scotland is the northernmost nation of the United Kingdom. Two-thirds of the population lives in the center portion of Scotland near the big cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh, and the northern areas are much more sparsely populated. Previous studies have shown that people who live in the western part of Scotland tend to be much less healthy and die younger than people who live in the east. Yet the Scottish Mental Survey data showed nothing of the usual east-west trend and seemed to indicate that those in the sparsely populated northern part of the country were more at risk for dementia than those in the south. “This was a puzzle that I really wanted to try to wrap my head around,” recalled Dr. Russ.

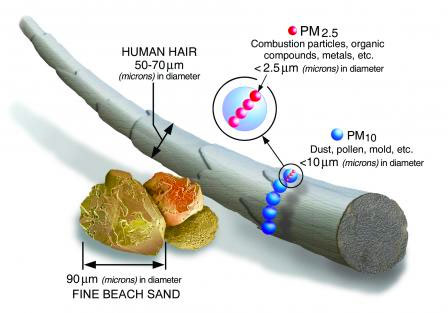

Patterns of geographical variation like those seen in the Lothian Birth Cohort can be related to numerous environmental factors including pesticides, vitamin D exposure, and air pollution. Dr. Russ decided to focus first on air pollution because it is the environmental variable that has been the most studied. In particular, Dr. Russ focused on fine

particulate matter

under 2.5 micrograms known as PM2.5.

Figure 7. Size comparisons of particulate matter

[Source: https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics]

Most of the research into air pollution has focused on acute exposure. For example, in February 2020, What A Year highlighted the work of Dr. Brokamp and colleagues who found a connection between poor air quality and increased hospitalizations due to mental health crises in adolescents. In the model of air pollution Dr. Brokamp developed, air pollution was measured one day, two days, and one week prior to hospitalization. In contrast, Dr. Russ wanted to know how exposure to air pollution over the course of a lifetime could impact cognitive status. This was difficult to model because modern air pollution data goes back only about 30 years.

Modeling Air Pollution of the Past

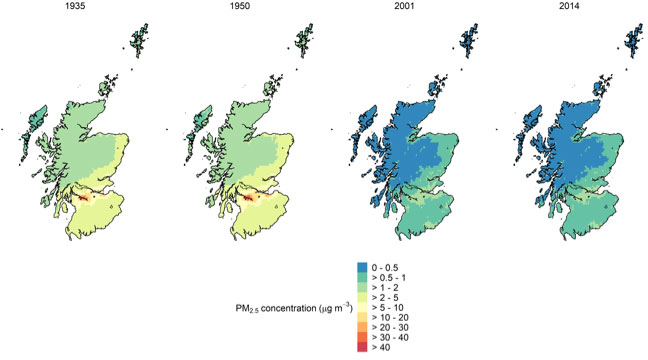

In order to develop a model of air pollution over the course of a lifetime, Dr. Russ and colleagues used modern meteorological (weather) data to create estimates of air pollution in the years prior to data collection. To begin, the researchers considered the different historical factors that might have affected air pollution, including population size, factory locations, and historical meteorological data. With this information, the researchers then looked at more recent meteorological data to find a more recent year with similar weather patterns. The air pollution data from that year could then be used as an estimate. For example, in 1935, the weather patterns in Europe were similar to that of 2011, so the researchers used the air pollution data from 2011 as an estimate for the air pollution in Europe (including Scotland) in 1935. A similar process was used for the years 1950, 1970, 1980, and 1990.

Figure 8. Models of PM2.5 concentration in 1935, 1950, 2001, and 2014, showing a decrease in PM2.5 concentration between 1950 and 2001

[Source: Image courtesy of Edward Carnell]

This study included 572 participants in the Lothian Birth Cohort for whom the researchers were able to obtain addresses (called residential history) over the course of their lives. The average number of residences for participants was 11 locations, with a range from 6 to 27 moves. The researchers used results from the Scottish Mental Survey (now called the Moray House Test) taken at ages 11, 70, 76, and 79 years. In addition to air pollution exposure, other variables the researchers considered included test results at age 11, occupation (an indication of socioeconomic status), smoking status, and gender.

The major finding of this study is that participants who were exposed to higher levels of air pollution in 1935 (when their mothers were pregnant with them) had greater decreases in cognition at age 70 than those who were exposed to lower levels of air pollution. “This is a really important finding because it shows the possibility of a connection between lifetime air pollution exposure and cognition,” explained Dr. Russ. There has been no research conducted on the long-term effects of air pollution because no one has been able to measure it. The changes Dr. Russ and his team observed between ages 11 and 70 years show that there is more research that needs to be done in this area. “Now that we know this is possible, it gives us the guidance we need to do further research with better, more detailed modeling.”

The Future

There are three key areas of research that Dr. Russ and his colleagues plan to explore in future research on air pollution and cognitive decline.

- When in life does exposure to air pollution have the most impact? It may be the case that the relationship between dementia and air pollution is a matter of straight-forward accumulation, meaning that the more exposure over the course of a lifetime the greater the risk. However, for many conditions exposure can be more damaging at certain points in time, such as during early childhood or adolescence. Dr. Russ and colleagues want to better understand whether all air pollution is equal in terms of dementia risk and whether air pollution at certain times in life can be more damaging.

- Which pollutant or group of pollutants causes the most dementia risk? For this study, Dr. Russ and colleagues focused on the pollutant PM2.5 because it has been the most studied. They wanted to see if this type of historical modeling of air pollution was possible. Future research will include other air pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide.

- Are there certain types of dementia that are associated with air pollution exposure than others?

Specific next steps for the research include repeating the study with improved modeling of air pollution and other pollutants in addition to PM2.5.

It is important to note that not everyone will experience cognitive decline or dementia in old age. Just as there are risk factors for developing cognitive problems, there are ways to decrease risk and promote brain health. Just as Dr. Russ studies cognitive decline, he also studies what is known as

cognitive reserve.

Cognitive Reserve and You

Cognitive reserve refers to the protective factors that help the brain become more resilient to cognitive changes. Many of the activities that promote protective factors are things you can start doing right now or you might already be doing, like eating a healthy diet filled with fruits, vegetables and whole grains, getting regular exercise, and not smoking. These lifestyle habits are not just for your brain – they protect your heart, your lungs, and your whole body.

Perhaps the best way to protect your growing brain against future cognitive decline is staying in school. Research shows that educational achievement when you’re young is one of the best ways to protect your brain in the future. As Dr. Russ concludes, “the bottom line is that dementia is not inevitable, and you are never too young to start protecting your brain.”

Dr. Tom Russ is a Consultant Psychiatrist in the UK National Health Service and Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturer at the Alzheimer Scotland Dementia Research Centre and Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. As a trainee psychiatrist, Dr. Russ worked in adolescent psychiatry at the Tavistock Clinic in London, where he became interested in how our experiences as young people affect us as we age. With the support of mentors, Dr. Russ trained in geriatric psychiatry and continues to work as a practicing clinician and researcher. When not in the laboratory, Dr. Russ enjoys reading, going to the movies, and spending time with his family.

For More Information:

- Russ, T. et al. 2021. “Life Course Air Pollution Exposure and Cognitive Decline: Modelled Historical Air Pollution Data and the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 79(3): 1063-74. https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-alzheimers-disease/jad200910

- Russ, T. et al. 2019. “Air pollution and brain health: defining the research agenda.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 32(2): 97-104. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30543549/

- Deary, I. et al. 2007. “The Lothian Birth Cohort 1936: a study to examine influences on cognitive ageing from age 11 to age 70 and beyond.” BMC Geriatrics, 7:28. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2222601/.

- Deary, Whalley, and Starr. 2009. A Lifetime of Intelligence: Follow-up Studies of the Scottish Mental Surveys of 1932 and 1947. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/4318049

To Learn More:

Dementia

- National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-dementia-symptoms-types-and-diagnosis

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/dementia/index.html

- World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia

Air Pollution and Health

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/air-pollution/index.cfm

- Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/air-pollution-current-and-future-challenges

- World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/airpollution/ambient/health-impacts/en/

- Environmental Defense Fund. https://www.edf.org/health/health-impacts-air-pollution

Lothian Birth Cohort

- University of Edinburgh. https://www.ed.ac.uk/lothian-birth-cohorts

- National Museums Scotland. https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/science-and-technology/made-in-scotland-changing-the-world/scottish-science-innovations/the-lothian-birth-cohort/

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |