| |

Highlights

Researchers developed a model to study the connection between air quality and mental health in adolescents. The model accounted for air quality, weather, and information on each neighborhood such as the number of vehicles, amount of greenspace, schools, household income, health insurance coverage, and education level. The researchers found that levels of particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns (PM2.5), which are considered “safe” by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), were related to increased risk for all types of acute psychiatric emergency department visits including for depressive episodes, mood disorders, and behavioral problems. The strongest relationship was between air pollution and thoughts of or attempts at suicide. When specifics of each neighborhood were considered, the strong correlation found between PM2.5 and risk of emergency room visits for suicide was true only for patients who lived in under-resourced neighborhoods with high rates of poverty, low rates of educational attainment, low health insurance coverage rates, and high rates of vacant housing.

Did you know that air quality can affect your health? Many studies have shown a connection between air quality and health conditions like

asthma

and

allergies.

New research by Dr. Cole Brokamp and colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital suggests that there may also be a connection between air quality and

mental health.

Pollution in the Air

Air is all around us. It’s mostly composed of nitrogen (78%) and oxygen (21%), with much smaller amounts of

argon,

carbon dioxide, and other gases. Especially in the last 100 years, though, air has also become a major site of pollution. Sources of this air pollution include transportation (cars, trucks, planes), agriculture, power plants, and oil refineries, among others.

Common air pollutants include

nitrogen dioxide,

ozone,

and

particulate matter.

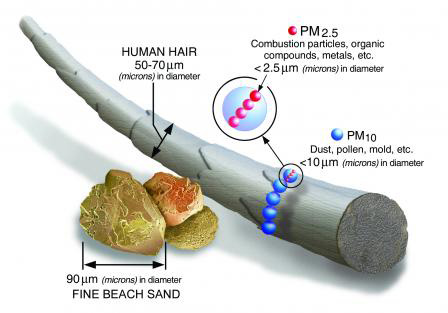

Particulate matter (PM) is a broad term used to describe particles found in the air, and it is usually classified by size, such as PM2.5.

Figure 1. Relative sizes of particulate matter

[Source: https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics]

At very high concentrations, like when smoke is emitted from fires or industrial sites, particulate matter is visible to the human eye. Most particulate matter, though, is microscopic and invisible.

Air pollution can be very dangerous because you don’t know or feel what you are breathing in and how it might affect your health. For this reason, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is tasked with regulating and monitoring air pollution across the United States. At specific locations across the country, the EPA has sites that regularly test air quality for the most common air pollutants, including particulate matter.

For health research, levels of PM2.5 are most concerning because these small particles can easily enter the body and cause health problems. To monitor particulate matter, researchers use an air filter to weigh the amount of matter captured in one cubic meter of air. The

EPA

defines a safe level of PM2.5 as 35 micrograms over a 24-hour period, which is about the weight of one human eyelash.

EPA air quality testing is a good start for understanding pollution in the air, but it doesn’t go far enough. Air pollution varies widely based on neighborhood, and people living in close proximity to each other can still be exposed to different amounts of particulate matter. This is why Dr. Brokamp and colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital wanted to create a model that could estimate air pollution at the neighborhood level across Hamilton County, where most of their patients live. Hamilton County includes the city of Cincinnati and surrounding area and towns.

Modeling Air Pollution

To create this model, Dr. Brokamp and colleagues began with publicly available air quality data from the EPA. The researchers then added information that would improve the model by including the number of trucks on the roads at given times in each neighborhood, the amount of greenspace in each neighborhood, optical data from satellites about how translucent the air is, and weather variables like temperature and humidity. All this information was inputted into computer systems to create a model that would predict air pollution at the neighborhood level across Cincinnati and surrounding Hamilton County.

The researchers tested this model of air pollution over and over in different neighborhoods in the county. First, they used it to predict air pollution levels in places where the exact number was known. Once the model was validated, the researchers used the model to estimate air pollution levels in sites without exact data.

Air Pollution, Asthma, and Mental Health

Dr. Brokamp and his colleagues were interested in using this model of air pollution to study the connections between air pollution levels and health. In particular, the researchers were interested in how the mental health of the population might be affected by air pollution. “We know that increased air pollution can cause flare-ups in physical diseases like asthma and allergies,” commented Dr. Brokamp. “We wanted to see if there might be a similar connection between air pollution and flare-ups of mental health disorders.”

Mental health disorder

is an umbrella term used to describe a wide range of conditions, including

depression,

anxiety,

and other

mood disorders.

These are all conditions that can be treated and managed with a combination of

psychotherapy,

medications, and, if necessary, hospitalization and

residential treatment.

Just like with many physical conditions, the severity of mental health disorders can vary over time. In other words, some days may be better than others.

For this research, Dr. Brokamp and colleagues hypothesized that some mental health disorders might cause symptoms in a similar way to asthma. Asthma is a

chronic

condition where patients have heightened levels of

inflammation

in the airways. On some days, the asthma might be well controlled, and the person with asthma goes about life normally. Sometimes, though, the symptoms might worsen, due to activity level, environmental conditions, or other factors, leading to an

asthma attack.

For many mental health disorders, the experience of the condition has similarities to asthma. Although mental health disorders are not always chronic in the same way as asthma, they usually last for a prolonged amount of time. On some days, the condition is well controlled, through medications, therapy, and other treatment methods. For a variety of reasons, though, the symptoms can get worse, causing an

acute psychiatric episode.

An acute psychiatric episode for a child or adolescent might look like a severe depressive episode, aggression or behavioral problems,

panic attacks,

and thinking about or attempting suicide.

Air pollution is known to both lead to the development of asthma in children and to cause acute asthma attacks. For this reason, Dr. Brokamp and colleagues wanted to investigate whether air pollution might also be a contributing factor in acute psychiatric episodes.

Air Pollution and Mental Health Studies

To investigate this potential connection, Dr. Brokamp used the health records of patients who came into the emergency room at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital for an acute psychiatric episode between 2011 and 2015. Only patients who lived within Hamilton County were included in this study because the air pollution model was only validated within this area.

Figure 2. GIF of different air pollution estimates for one month in Hamilton County

[Source: http://colebrokamp-dropbox.s3.amazonaws.com/Hamilton_June_2010_PM25.gif]

The researchers found a total of 13,176 acute psychiatric episodes that met the inclusion criteria, representing 6,812 individual patients. Of these patients, 64% had only one emergency room visit for an acute psychiatric episode over the study period; 18% had two visits; and 18% had three or more visits. The average age at the time of the emergency room visit was 14.4 years. The most common reasons for the emergency room visit were depressive episodes, other mood disorders, and behavioral problems.

For each patient in the study, Dr. Brokamp and his colleagues used the air pollution model to estimate the amount of air pollution in the neighborhood where the patient lived on the day they came into the hospital; one day, two days, and one week before they came into the hospital; and one week after they came into the hospital. In this way, the researchers determined if the air pollution had increased prior to the emergency room visit.

In the first study, Dr. Brokamp and his colleagues wanted to know whether there was a connection between increased air pollution and acute psychiatric episodes. They found that levels of PM2.5 considered “safe” by the EPA were related to increased risk for all types of acute psychiatric emergency department visits including for depressive episodes, mood disorders, and behavioral problems.

Next, the researchers wanted to dig deeper, to see if there was a stronger connection between certain types of psychiatric episodes than others. They found the strongest relationship to be between air pollution and

suicidality—

either thoughts of or attempts at suicide. An increase of PM2.5 by 10 micrograms/cubic meter doubled the risk of a patient coming to the emergency room for suicidality. “These results were really surprising,” remarked Dr. Brokamp. “This is the strongest effect of air pollution that we’ve seen in any study to date.”

It is important to note that the increases that Dr. Brokamp and colleagues are measuring are still under the EPA’s legally safe limit for PM2.5. As Dr. Brokamp concludes, “I don’t believe there is such a thing as a safe level of air pollution.”

Unequal Air

The results of this study further emphasize what many communities already know: we don’t all breathe the same air. Families and communities don’t choose to be next to highways and industrial facilities, both known causes of air pollution and PM2.5 emissions. In fact, it’s just the opposite. Families with more money will choose to live farther from sources of pollution, meaning that it is the poorest families, often families of color, who live in closest proximity to pollution.

This also means that air pollution is only one of many challenges these communities are dealing with. In general, families living in more polluted areas also typically have access to worse schools, fewer green spaces, and fewer economic resources. This reflects political decisions made at the local, state, and federal level to invest in some communities (largely white and wealthier) more than others (largely people of color and poorer).

For this reason, Dr. Brokamp and colleagues looked not only at neighborhood levels of air pollution but also the level of investment at the neighborhood level. Investment levels were determined using previous research conducted by Dr. Brokamp that included variables such as household income, health insurance coverage, and education level. This information came from the 2015 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The strong correlation Dr. Brokamp found between PM2.5 increase and risk of emergency room visits for suicidality was much stronger for patients who lived in neighborhoods with low levels of investment (worse schools, limited green space and economic resources). However, for patients who lived in high investment neighborhoods (better schools, more green space and economic resources), increased air pollution did not increase their risk of an acute psychiatric episode as much.

In other words, these results show that even if those living in low investment neighborhoods breathed the same concentrations of air pollution than those living in high investment neighborhoods, they would still be at a higher risk of psychiatric exacerbations.

Future work

Dr. Brokamp is quick to point out the limitations of this study. First, this type of study is known as an

observational study.

This means that the researchers are observing data from events that have not been randomly assigned. Unlike in a clinical trial, it is not ethically feasible to randomly expose human subjects to high and low levels of air pollution. One of the advantages of this type of study is that it can be conducted relatively quickly and inexpensively. One major disadvantage, though, is that it can be difficult to draw clear causal conclusions because other factors that co-vary with air pollution might also co-vary with increased risk of psychiatric exacerbations. Some of these factors, such as weather and holidays, were accounted for in the statistical model, but other unknown and unmeasured factors could also be present.

In the current study, it was not possible to ask patients about stressors in their lives, or about what they think was the cause of their visit to the emergency room.

Racism,

poverty,

and challenges at school or at home can all play a role in worsening an underlying condition – be it asthma or a mental illness.

In future work, Dr. Brokamp would like to dive more deeply into the experiences of individual patients. This could mean giving patients a survey to learn more about them from their own perspectives. It could also mean taking blood samples from patients to measure markers of stress and inflammation.

It is important to remember that this is the very first study to find a relationship between air pollution and mental illness. “This means that it is way too soon to give any sort of recommendations based on the results,” says Dr. Brokamp. Instead, Dr. Brokamp wants to focus on the broader picture, on the ways that the environment affects our health.

There is a large body of research showing how air pollution causes worse health outcomes. Some of these conditions can be treated or managed by doctors, but the real solutions lie in limiting air pollution, and all types of pollution. “What if we could prevent asthma and the development of worse mental health by creating public policies informed by scientific research?” asks Dr. Brokamp. Taken together with many other studies on the effects of air pollution, the results from this research show that public policy may be the best medicine.

Dr. Cole Brokamp is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati, which is affiliated with Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Dr. Brokamp studies the effects of air pollution and other neighborhood-level variables and how they affect the health of children and adolescents. When not in the laboratory, Dr. Brokamp enjoys playing the keyboard, attending sporting events at the University of Cincinnati, and spending time with his family.

For More Information:

- Brokamp, C. 2019. “Pediatric Psychiatric Emergency Department Utilization and Fine Particulate Matter: A Case-Crossover Study.” Environmental Health Perspectives, 127:97006-097006.

- Brokamp, C. et al. 2018. Predicting Daily Urban Fine Particulate Matter Concentrations Using Random Forest. Environmental Science & Technology. 52 (7): 4173-4179. https://colebrokamp-website.s3.amazonaws.com/publications/Brokamp_EST_2018_onlineaheadofprint.pdf

To Learn More:

Air Pollution and Health

- Air Pollution. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/air-pollution/index.cfm

- Clean Air Act Overview. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/air-pollution-current-and-future-challenges

- Air Pollution. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/airpollution/ambient/health-impacts/en/

- Health Impacts of Air Pollution. Environmental Defense Fund.https://www.edf.org/health/health-impacts-air-pollution

- Ambient (outdoor) air pollution. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health

- Particulate Matter Pollution.https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics

Child and Adolescent Mental Health

- Mental Disorders. TeenMentalHealth.org. http://teenmentalhealth.org/learn/mental-disorders/

- Child and Adolescent Mental Health. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/child-and-adolescent-mental-health/index.shtml

- Mental Health in Adolescents. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/adolescent-development/mental-health/index.html

- Adolescent Mental Health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |

|

|

Dr. Cole Brokamp

Dr. Andrew Beck

Dr. Jeffrey Strawn

Dr. Patrick Ryan

Sign Up for our Monthly Announcement!

...or  subscribe to all of our stories! subscribe to all of our stories!

What A Year! is a project of the Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research.

|

|