| |

How many of you packed a peanut butter sandwich today? Perhaps sweetened with jam, jelly, or Marshmallow Fluff®? According to the National Peanut Board,

an American child will eat an estimated 1,500 peanut butter and jelly sandwiches before graduating high school.

That's a lot of peanuts!

It is important to note that peanuts are also the leading food allergen in the United States and can cause severe allergic reactions in some children and adults. There is an entire field of research focused on food allergies and treatment options. This month, though, we will take a look at the potential health benefits of America's number one snack nut - the peanut.

Peanuts

Image from https://www.healthtap.com/topics/canola-oil-peanut-allergy

One serving of peanuts is one ounce, which is about the amount you would grab if you took a handful of peanuts for a snack. Peanuts are high in fat and calories and should therefore be eaten only in moderation. Nevertheless, they are generally considered to be a healthy food because of the types of fat they contain: lots of

unsaturated fats,

minimal

saturated fat,

zero

trans fats,

and no dietary cholesterol. One serving of peanuts provides 161 calories and contains:

7.3 grams of protein and 14 grams of fat. That 14 grams of total fat includes 6.9 grams

monounsaturated fat,

4.5 grams

polyunsaturated fat,

1.9 grams saturated fat.

You may be familiar with these different types of fats. They are required by law to be printed on every nutrition label. So what's the difference?

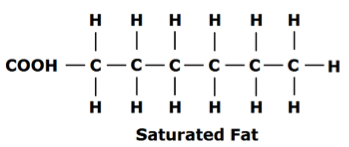

On a chemical level, all fats are chains of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. The particular size, shape, and bonding structure of the chains determines how readily they can be used by our bodies. Saturated fats are chains of carbon atoms attached to as many hydrogen atoms as possible-the carbon is fully saturated with hydrogen.

Chemical structure of saturated fat

[https://encrypted-tbn3.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcRUsOctz6PV0EnQjpl5iBk9Qed-od7jUY91IT-Mpcpjf1waRRYT7VvZurA]

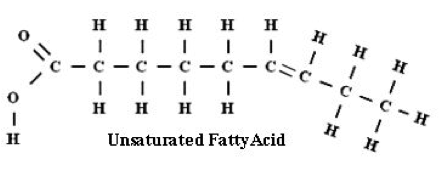

Unsaturated fats, on the other hand, are chains of carbon atoms with at least one less hydrogen atom - the carbon is not fully saturated with hydrogen. Monounsaturated fats have one less hydrogen atom than saturated fats, while polyunsaturated fats have at least two fewer hydrogen atoms.

Chemical structure of unsaturated fat

[https://grubfirst.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/unsaturated_fat.jpg]

Different food sources will generally provide different types of fats. Saturated fats are solid at room temperature and are generally found in animal products such as meat and dairy. In contrast, unsaturated fats are liquid at room temperature and are more prominent in fish and plant-based foods.

Natural trans fats are not harmful. They are found in some animal products such as dairy products, beef and lamb. In contrast, artificial trans fats are a byproduct of food processing and are rarely found in natural food sources. They are solid at room temperature and are used because foods made with them are less likely to spoil. In other words, these foods can stay on the grocery shelf a long time. Artificial trans fats in particular are damaging to our bodies because they cause inflammation and raise the levels of a specific type of cholesterol called low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, which contributes to heart (cardiovascular) disease. We will discuss fats and cholesterol next.

All fats - saturated and unsaturated - are necessary for life because they are the core component of cell membranes. Yet fat molecules are particularly difficult for our bodies to digest because they do not dissolve in blood or water. In order to transport fat molecules throughout the bloodstream, our bodies produce protein-covered particles that bind to the fat to form

lipoproteins.

There are three main types of lipoproteins:

high-density lipoproteins (HDL),

low-density lipoproteins (LDL),

and

triglycerides.

Both high-density and low-density lipoproteins transport

cholesterol,

a type of fatty acid. Low-density lipoproteins transport cholesterol from the liver, where it is produced, throughout the bloodstream to the rest of the body. High-density lipoproteins gather cholesterol from around the body and bring it back to the liver for disposal. Triglycerides are found in

chylomicrons

and very low-density lipoproteins, which are lipoproteins that transport dietary fats.

When we consume fats as part of our diet, the molecules are broken down into smaller pieces and utilized for a variety of purposes. Fat molecules may become LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, or converted into other lipids. How the body uses dietary fats depends on the type of fat.

Unsaturated fats decrease LDL cholesterol in the blood stream and, compared with dietary carbohydrate, they increase HDL cholesterol and decrease triglycerides. In contrast, saturated and trans fats increase LDL cholesterol. We do need some LDL cholesterol, but excess can harden into plaque that narrows blood vessels and cause blockages over time. They also stimulate

endothelial cells,

the cells that line the blood vessels, to release

inflammatory molecules

that can damage the ability of endothelial cells to protect our blood vessels.

Current nutrition science recommends a diet low in saturated fats and high in unsaturated fats. Nutrition scientists recommend that artificial trans fats be avoided entirely because they potently increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Over two decades of nutrition research has shown that peanuts in particular, eaten as part of a healthy diet, can help reduce the risk of heart disease,

diabetes

and

cancer,

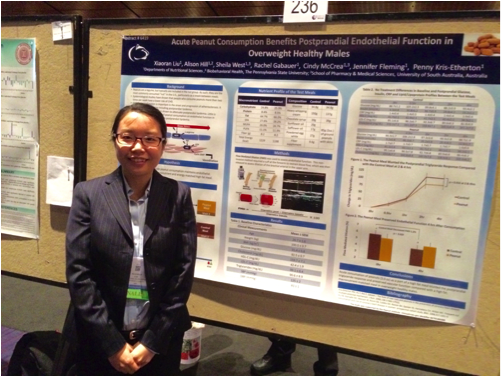

among other illnesses. Xiaoran Liu, a PhD graduate student working in the laboratory of Dr. Kris-Etherton at Pennsylvania State University, wanted to know why.

To understand how peanuts might differ from other types of nuts and seeds, Dr. Xiaoran Liu began in the kitchen. She created two milkshakes with the same nutrient profiles including the same amounts of saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. The only difference was the peanut content. The peanut meal contained 85 grams of ground peanuts with skins. The control meal contained 20 grams sunflower oil, 17 grams safflower oil, 27 grams powdered egg white, and 9.6 grams fiber supplement, a mixture carefully developed by Dr. Liu and her colleagues to match the nutritional profile of the peanuts.

Fifteen overweight men between the ages of 20 and 50 were invited to the laboratory once per week for two weeks and challenged to drink a large, high-fat milkshake for lunch. The first week the participants randomly received either the peanut meal or the control meal. The second week they received whichever meal they had not yet consumed. There was at least one week break between each visit.

Each week Dr. Xiaoran Liu and her team took one blood sample before each meal, which served as the control. Dr. Liu took four additional blood samples at 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 2 hours and 4 hours after the participant had finished the milkshake. The blood samples were used to measure blood sugar, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides and C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker.

In addition to the blood samples, Dr. Xiaoran Liu and her team measured the rate of blood flow four hours after the participants finished the milkshake. When blood vessels become inflamed, as they do after eating a high-fat meal, they tend to constrict. The constriction of blood vessels, known as

vasoconstriction,

makes it more difficult for oxygen and other nutrients to move throughout the bloodstream. If peanuts indeed protected against the inflammatory response to lots of fat molecules, Dr. Xiaoran Liu expected to see differences in vasoconstriction.

Ultrasound of arterial width as measured by flow mediated dilation.

To measure vasoconstriction (and the opposite,

vasodilation),

Dr. Xiaoran Liu used a test called flow-mediated dilation or FMD. FMD is a non-invasive procedure similar to getting your blood pressure taken. A cuff is placed on the upper arm to restrain blood flow in the upper arm for six minutes. When the cuff is released, the researchers measure the vascular dilation in the brachial artery of the upper arm.

Dr. Xiaoran Liu and her team observed no significant differences between the two meals in any of the blood tests at baseline, 30 minutes post-meal, and 60 minutes post-meal. At two and four hours post-meal, however, the researchers observed a significant decrease in triglyceride levels in the participants who had consumed the peanut meal compared with the control meal. There was no difference between any other biomarkers tested. The participants who had consumed the peanut meal prevented vasoconstriction and maintained vasodilation, preserving blood flow and allowing for greater uptake of triglycerides.

Since hormone cycles influence some of the chemical markers tested, Dr. Xiaoran Liu conducted this initial study with only male patients. She believes the same results would be found in women.

Dr. Xiaoran Liu hypothesizes that peanut consumption has beneficial effects, in part, because peanuts contain

arginine,

an

amino acid.

Arginine is converted to nitrous oxide, which promotes increased blood flow. The presence of this molecule may therefore counteract some of the inflammation that occurs after eating a high-fat meal. Future work will explore the role of arginine in the inflammatory process. In addition to peanuts, some tree nuts such as walnuts and pecans also contain arginine. Follow-up experiments are needed to compare peanuts to other tree nuts containing arginine.

For now, Dr. Xiaoran Liu's research confirms previous nutritional findings that peanuts can have beneficial health effects when eaten as part of a balanced diet. Peanuts can be part of a heart healthy diet, and consumed frequently. Just remember, peanuts are high in fat and calories, and are best eaten in small amounts as a replacement for other calorie dense foods.

Peanuts, anyone?

Dr. Xiaoran Liu was a graduate student who received her PhD in the laboratory of Dr. Penny Kris-Etherton in the Department of Nutritional Sciences at the Pennsylvania State University. This research was part of her PhD thesis. Dr. Xiaoran Liu plans to continue her postdoctoral training in clinical nutrition and dietary interventions. Outside of the laboratory she takes care of her horse and is an avid horseback rider and amateur photographer.

For More Information:

- Liu X, Hill A, West S, Gabauer R, McCrea C, Fleming J, Kris-Etherton. Acute peanut consumption benefits postprandial endothelial function in overweight healthy males. Experimental Biology 2015. Poster #6419.

To Learn More:

- Nutrition and Healthy Eating. Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/fat/art-20045550

- Digestion and Absorption of Fats. http://courses.washington.edu/conj/bess/fats/fats.html

- Trans fats. American Heart Association. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/NutritionCenter/HealthyEating/Trans-Fats_UCM_301120_Article.jsp

- Good vs. Bad Cholesterol. American Heart Association. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Cholesterol/AboutCholesterol/Good-vs-Bad-Cholesterol_UCM_305561_Article.jsp

- Nuts and Your Heart: Eating Nuts for Heart Health. Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/nuts/art-20046635

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |

|

|

Dr. Xiaoran Liu presenting the research results in a poster session at the Experiment Biology Conference in Boston.

Student Rachel Gabauer, an undergraduate student who assisted Dr. Xiaoran Liu with the peanut study.

When not in the lab, Dr. Xiaoran Liu can be found caring for and riding her horse.

Peanuts aren't nuts and other neat trivia

Sign Up for our Monthly Announcement!

...or  subscribe to all of our stories! subscribe to all of our stories!

What A Year! is a project of the Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research.

|

|