Highlights

- Triple negative breast cancer accounts for 10 to 20% of all breast cancers. It primarily affects African American women.

- Triple negative breast cancer does not respond to conventional cancer treatments because it lacks the hormone receptors these drugs target.

- Rosehip extract decreased the growth of triple negative cancer cells and prevented cell migration in vivo. Rosehips worked well by itself and in combination with traditional chemotherapy.

It is amazing to think that a treatment for cancer is already growing in your backyard or local park. New research by Dr. Patrick Martin and colleagues at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University suggests just that. In particular, Dr. Martin has focused on rose hips—the fruit of the rose plant—as a novel source for the treatment and prevention of cancer.

Source: http://gardening.about.com/od/rose1/f/RoseHips.htm

Rosehips

We are surrounded by plants that—without access to a doctor—have developed natural compounds to fight infection and disease. Dr. Martin first learned about rosehips when a colleague asked him to attend a student presentation about research using plant extracts to fight colorectal cancer. This work was being done in the School of Agriculture at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, with the goal of finding medicinal properties in plants that were growing—often unwanted—in the crop fields. “As a cell biologist, I thought this was interesting,” explains Dr. Martin. “But I wanted to know why.”

At the time, Dr. Martin was conducting research on brain cancer. In collaboration with colleagues in the School of Agriculture, Dr. Martin decided to see how rosehips might affect brain cells. He obtained rosehip extract from his colleagues and applied the extract directly to petri dishes filled with growing brain tumor cells. To his surprise, Dr. Martin observed that the rosehip extract halted the growth of brain tumor cells.

Triple negative breast cancer — Few good treatment options

Just as these initial experiments were concluding, Dr. Martin received a grant to research health disparities in breast cancer. His laboratory focused in on a type of breast cancer called

triple negative breast cancer,

or TNBC, a particularly aggressive type of breast cancer. TNBC accounts for an estimated 10 to 20 percent of all breast cancer cases and primarily affects African American women.

Comparison of Triple Negative Breast Cancer cell lines with non-Triple Negative Breast Cancer cell lines.

There are three

hormones

that control the majority of normal breast tissue growth and function:

estrogen,

progesterone,

and

epidermal growth factor.

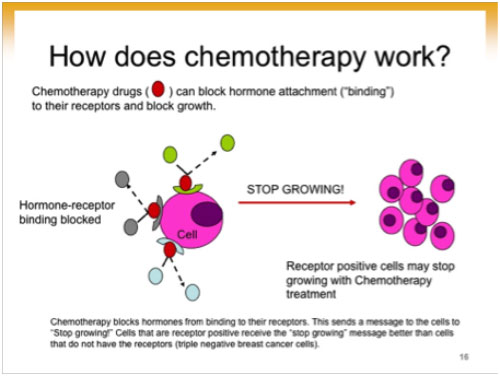

These hormones regulate breast cell function by interacting with specific receptors in breast cells, namely the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and the HER2/neu receptor for epidermal growth factor. In some types of breast cancers, one or more of these receptors may become dysfunctional, causing or allowing unregulated cell growth that results in breast tumors. Many breast cancer treatments target these receptors to restore regulatory function and halt tumor growth.

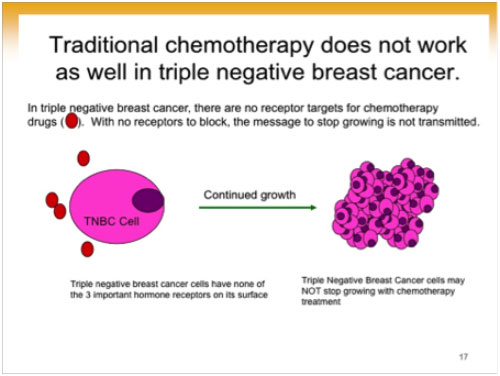

Explanation of how chemotherapy works.

However, unlike typical breast tumor cells, triple negative breast tumor cells lack all three receptors. This is how triple negative breast cancer gets its name. This is also why triple negative breast cancer is so difficult to treat—because it lacks the receptors that most treatments target. For this reason, the standard treatments for breast cancer are much less effective in TNBC. “We are always in need of better treatments for all types of cancers,” explains Dr. Martin. “But the treatment options for TNBC are really minimal. We need to figure out how to fight this disease.”

Explanation of why chemotherapy does not work for triple negative breast cancer.

Having shown that rosehips inhibited the growth of brain tumors, Dr. Martin and his research technician, Patrice Cagle, conducted similar experiments using cancer cells obtained from African American women with TNBC. The first set of experiments tested the rate of cell growth, known as

cell proliferation,

in tumor cells treated with rosehips compared to controls.

The rosehip treatment was prepared by directly mixing the rosehip extract into the

media

of the petri dish for a final concentration of 0.25 to 1.0 mg/ml. The media contains all the nourishment needed for cells to grow. Dr. Martin and Patrice compared the growth of TNBC cells in an untreated environment (control) with TNBC cells grown in media containing the rosehip extract (treated). “Once again we found that rosehips effectively reduced cell growth in tumor cells,” remarks Dr. Martin. On average the researchers observed a fifty percent reduction in cell growth in TNBC cells treated with rosehip extract.

“We showed that rosehips—this common plant that we see all around us—works better than cancer treatments already available. We’re definitely excited about these results.”

In follow-up experiments, Dr. Martin and Patrice tested the ability of TNBC cells to move from one location to another, known as

cell migration.

In humans, this process is called

metastasis,

when cancer spreads to other parts of the body like the lungs, bones or brain. Inhibiting metastasis is critical to treating all types of cancers.

To measure cell migration in the laboratory, Dr. Martin and Patrice first placed the tumor cells in an untreated petri dish and allowed the cells to grow until they completely filled the petri dish. The researchers then created a “wound” by scraping away a line of cells directly through the petri dish. Cell migration was measured by how rapidly the remaining cells migrated to fill the “wound”.

In the control experiments, the TNBC cells exhibited a nearly one hundred percent migration rate—within hours the researchers observed new growth and within 24 hours the “wound” was no longer visible. “Wounds” treated with rosehip extract, however, were completely different. The researchers tested several concentrations of rosehip extract, with the greatest concentration leading to a thirty percent decrease in cell migration.

Next, Dr. Martin and Patrice compared these results to similar experiments performed using currently available treatments for breast cancer. They compared the results of rosehips alone with a common chemotherapy for breast cancer called

doxorubicin,

and both rosehips and doxorubicin in combination. They found a) the rosehip extract worked well all by itself and, b) rosehips and doxorubicin decreased cell proliferation and migration in TNBC tumor cells.

Referring to the first result, Dr. Martin said “we showed that rosehips—this common plant that we see all around us—works better than cancer treatments already available. We’re definitely excited about these results.”

The second result suggests that rosehip extract might be beneficial when added to current breast cancer treatments.

In many types of cancer, the signaling pathways go into overdrive, telling the cells to keep growing even when they shouldn’t be. Dr. Martin thinks rosehips stops this errant communication before it gets to the nucleus, thereby preventing cell growth.

Dr. Martin remarks “there is still much more research to be done before rosehips becomes a common treatment at the hospital.” The next step is to try similar experiments in mouse models of breast cancer. Experiments are also underway to better understand how rosehips are affecting cancer cells. Dr. Martin hypothesizes that rosehips interfere with cell signaling pathways known to promote cell growth in TNBC, called

mitogen-activated protein kinases

(MAP kinase) and

protein kinase B.

In many types of cancer, the signaling pathways go into overdrive, telling the cells to keep growing even when they shouldn’t be. Dr. Martin thinks rosehips stops this errant communication before it gets to the nucleus, thereby preventing cell growth.

The use of readily available plant extracts to treat aggressive cancers is one important aspect of Dr. Martin’s research. “I was trained as a cell biologist,” explains Dr. Martin. “I was skeptical that this could really work.” Rosehips are high in vitamin C and are a common ingredient in teas and other herbal remedies around the world.

Dr. Martin’s research is unique for two other reasons. First, Dr. Martin highlights the fact that North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College is first and foremost an educational institution. “We are not known as a high class research institution,” comments Dr. Martin. “But we are doing high class research with undergraduate students, even high school students. Not only are we doing high class research, we are also training the next generation of scientists.” In fact, Patrice Cagle, the research technician working with Dr. Martin on these experiments, is now a doctoral student in his laboratory.

Finally, Dr. Martin emphasizes that this research was conducted to address health disparities in breast cancer. Triple negative breast cancer affects primarily African American women, and the available treatments are known to be less effective against the disease. This research was conducted by African Americans for African Americans. “We need more scientists of color addressing the needs of their communities,” concludes Dr. Martin. “I am proud to be a part of this research community.”

Dr. Patrick Martin is Associate Professor of Biology at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Greensboro, NC. His research focuses on the molecular biology of brain and breast cancer and the effects of natural products. Dr. Martin received his Ph.D. in cell biology from the University of Virginia, the first African American to do so. When not in the laboratory, Dr. Martin enjoys spending time with his family, grilling and boating.

Patrice Cagle is a doctoral student in Dr. Martin’s laboratory. Patrice loves relaxing and spending time with her family and her cat. She loves to read, and write poems and is a member of the Writer’s Group of the Triad (WGOT). She has recently published a memoir entitled “My Sustainer.” During her spare time, Patrice enjoys giving back to her community and is very involved in her church, where she teaches children’s church, sings in multiple choirs, and is an advisor for the youth. She is passionate about bringing awareness of the impact of breast cancer in African American women and was the guest speaker at a local church during their breast cancer awareness service. She has volunteered for numerous organizations combatting abuse and domestic violence such as Family Services of the Piedmont and Exhale Victim Alliance. Patrice also enjoys volunteering to feed the homeless in her local community as well as her church community.

For More Information:

- Cagle P, Coburn T, Shofoluwe A, Martin P. Rosehip (Rosa canina) extracts prevent cell proliferation and migration in triple negative breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 2015;29:629.14

To Learn More:

Triple Negative Breast Cancer

- Triple Negative Breast Cancer Foundation. http://www.tnbcfoundation.org/understandingtnbc.htm

- American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/detailedguide/breast-cancer-classifying

- Breastcancer.org. http://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/diagnosis/trip_neg

- Black Women’s Health Imperative. http://www.bwhi.org/issues-and-resources/black-women-and-breast-cancer/

Health Disparities and Cancer

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/healthdisparities/basic_info/index.htm

- National Cancer Institute. http://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/crchd/cancer-health-disparities-fact-sheet

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. http://www.cancer.net/research-and-advocacy/health-disparities-and-cancer

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |