| |

Highlights

- Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease believed to be associated with repeated hits to the head.

- Researchers at the CTE Center found that players who started playing football before age 12 years were twice as likely to report problems with behavioral regulation, apathy, and executive functioning, as well as three times as likely to report clinically depressive symptoms. These symptoms began earlier in players who began tackle football before 12 years of age. In another study of deceased tackle football players, for every one year younger the individuals began to play tackle football, the onset of cognitive problems decreased by 2.4 years and the onset of behavioral and mood problems decreased by 2.5 years.

- The findings suggest that starting to play tackle football at a younger age, particularly before age 12 years, may lead to earlier onset of cognitive and emotional symptoms and can have negative consequences on neurobehavioral functioning later in life.

Football fans may have heard of Mike Webster or “Iron Mike,” as he is known in the Professional Football Hall of Fame. Webster took the Pittsburg Steelers to four Superbowl championships between 1974 and 1979, and continued playing for more than a decade, for a total of 17 years with the National Football League (NFL).

Mike Webster died at the age of 50 from a heart attack. However, his brain was neuropathologically examined because he experienced thinking, memory, mood, and behavioral problems during his life. The neuropathological examination revealed evidence of

chronic traumatic encephalopathy

(CTE). Mike Webster is known as the first former NFL player to be diagnosed with CTE.

CTE is a progressive

neurodegenerative

disease believed to be associated with repeated hits to the head. The history of CTE dates back to 1928 when Dr. Harrison Martland used the term “punch-drunk syndrome” to describe a cluster of clinical symptoms in boxers. CTE, however, did not emerge at the forefront of scientific and societal attention until it was linked to participation with American football in 2005.

The

neuropathological

and clinical features of CTE have become increasingly well-defined through the extensive and ongoing research at Boston University CTE Center. Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology and Pathology at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM), directs the Veterans Affairs (VA) – Boston University (BU) – Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) brain bank, where former American football players and other individuals with a history of exposure to repeated head impacts donate their brains after death for scientific research. Dr. Robert Stern, Professor of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Anatomy & Neurobiology at the BUSM, directs the Clinical Research of the BU CTE Center and has an ongoing, seven-year, multisite study devoted to the investigation of the diagnosis, risk factors, and

biomarkers

of CTE in living former tackle football players. Drs. Michael L. Alosco and Jesse Mez are key investigators on the Clinical Research Team at the BU CTE Center who are closely involved and help lead the ongoing clinical and neuropathological studies of CTE and other disorders.

At this time, CTE cannot be diagnosed during life and can only be diagnosed after death through an examination of the brain using criteria developed by Dr. McKee (McKee et al. 2016). In addition to developing methods to diagnose CTE during life, a goal of the BU CTE center is to identify potential risk factors. One risk factor that has been a particular focus of the BU CTE Center is the age that an individual begins to be exposed to repetitive head impacts through contact or collision sports, namely tackle football. Indeed, many individuals begin to play tackle football at a very young age, including as young as 5 years old.

“The child and adolescent brain are extremely fragile,” remarked Dr. Michael Alosco, Assistant Professor of

Neurology

at the Boston University School of Medicine. “Our research suggests that we need to be more careful when exposing young children to repeated head injuries.”

Dr. Alosco is a clinical

neuropsychologist,

with expertise in dementia disorders. He has specific clinical training in the evaluation and assessment of older adults with memory problems. As a neuropsychologist, Dr. Alosco is trained to administer neuropsychological tests that assess thinking, behavior, and mood, and to use that information to assist with diagnosis and planning treatment. His research has been devoted to the investigation of the diagnosis, risk factors, and in vivo biomarkers of neurodegenerative diseases, particularly

Alzheimer’s disease

and CTE. In his role at the CTE Center, Dr. Alosco conducts clinical interviews on the telephone with family members and other caregivers of deceased athletes who donate their brain to the VA-BU-CLF brain bank. He is also closely involved in ongoing studies that examine the clinical presentation and in vivo biomarkers of CTE in living tackle football players.

The Developing Brain and CTE

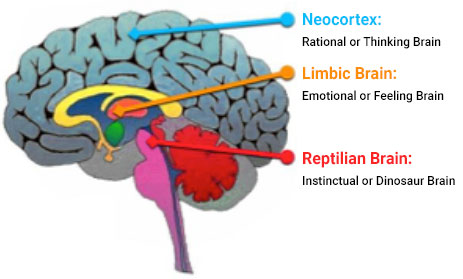

To better understand the research conducted by Dr. Alosco and the CTE Center research team, let’s begin with background on the developing brain and CTE. From an evolutionary perspective, the brain can be divided into three sections: the reptilian brain, the limbic brain, and the neocortex.

Figure 1. Picture of the brain

[Source: https://tinyurl.com/yak3wrfx]

The reptilian brain includes the brainstem and cerebellum. It is responsible for controlling our most basic functions like breathing, heart rate, hunger, and sleep. This part of the brain is fully developed by the time an infant is born. The limbic brain helps process emotions and respond to stress. It develops over time. The neocortex is responsible for our most complex cognitive functions. It is the newest part of the human brain, from an evolutionary perspective. This part of the brain is responsible for problem-solving, critical thinking, interpreting senses and emotions, and creativity. The most critical time for the development of the neocortex is between ages 5 and 12 years, although scientists believe that some aspects of the neocortex are not fully developed until the mid-20s.

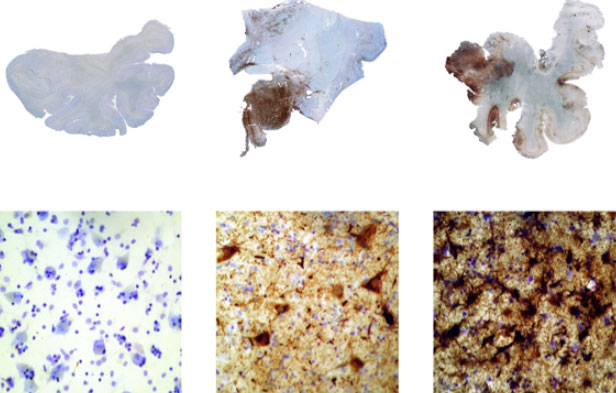

CTE is unique and unlike any other disease in terms of how it appears in the brain. Researchers have developed criteria for the diagnosis of CTE, but a diagnosis can only be confirmed after death through examination of brain tissue under a microscope. The ability to diagnose CTE before death through the use of various biomarkers is an area of ongoing research.

CTE is characterized by the misfolding of a protein called tau. In normal brains, tau protein helps stabilize cell structures, but in CTE and other neurodegenerative diseases, the protein misfolds and starts to form clumps in the brain, causing the death of brain cells. Over time, the brain tissue starts to shrink, and the openings in the brain become larger. CTE is often accompanied by psychological and cognitive symptoms including rage, aggression, depression, and other changes in mood and thinking that get progressively worse over time.

Figure 2. The medial temporal lobe from three individuals. The figure on the left is normal. The brown shows the abnormal tau protein seen in CTE.

[Photo courtesy of Dr. Ann McKee http://www.bu.edu/cte/about/frequently-asked-questions/]

Linking Football and CTE

Utilizing the VA – BU – CLF brain bank, CTE researchers led by Dr. Ann McKee neuropathologically diagnosed CTE in 177 of 202 or 87% of brains donated to the brain bank. Of the 177 participants diagnosed with CTE, 3 out of 14 were former high school players (21%), 48 out of 53 played at the college level (91%), 9 out of 14 played semi-professionally (64%), 7 out of 8 played in the Canadian Football League (88%), and 110 out of 111 played in the NFL (99%).

While the neuropathology of CTE has become well-defined over the years, risk factors and the overall clinical presentation of CTE remain less well understood. Much of the research at the CTE Center is focused on identifying risk factors for CTE or other long-term consequences related to repeated hits to the head. One risk factor of interest is the age of first exposure to football. This is because the young brain is constantly developing, particularly before the age of 12 years, and repeated hits to the head might interfere with normal brain development and increase an individual’s vulnerability to later-life cognitive, behavior, and mood problems. Research outside of BU has found that a single season of youth football can lead to changes in the white matter of the brain (Bahrami et al. 2016). Previous studies at the CTE Center have shown that former NFL players who started playing football before age 12 had greater cognitive impairments, as well as worse white matter integrity of the corpus callosum later in life than those who first started playing football after age 12.

Age of First Exposure to Football and CTE

Dr. Alosco and the CTE Center research team sought to expand the findings in former NFL players to include football players who played at all levels (i.e., high school, college, and professional). This group of participants was from the Longitudinal Examination to Gather Evidence of Neurodegenerative Disease or LEGEND study. The LEGEND study includes current and former players of

contact sports

and non-contact sports across the U.S. The researchers examined 214 former high school, college, and professional football players from the LEGEND study. All the participants were male and did not participate in other contact sports aside from football at either the high school, college, or professional level. Participants completed a series of telephone and online tests annually to understand behavior, mood, and

cognition,

as well as demographic history, athletic history, and medical history. Cognitive tests included:

- Brief Test of Adult Cognition, a 20-minute cognition assessment administered over the phone.

- Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function - Adult Version, a self-reported questionnaire asking about

executive function

and

behavioral regulation.

- Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, a self-reported 20-minute survey of

depressive symptoms.

- Apathy Evaluation Scale, a self-reported survey of

apathy,

or loss of pleasure in things.

Like in the previous study, Dr. Alosco and the CTE Center research team divided the sample into participants who started playing football before age 12 years and those who started at 12 years or older. They found that players who started playing football before age 12 were twice as likely to report problems with behavioral regulation, apathy, and executive functioning, as well as three times as likely to report clinically depressive symptoms. These findings were independent of the total number of years the participants played football or at what level they played. Results remained even when the age cutoff was not used. This study provided further evidence that starting to play football before age 12 years can have negative consequences on neurobehavioral functioning later in life.

Next, Dr. Alosco and the CTE Center research team sought to examine the relationship between age of first exposure to football and CTE pathology and clinical severity. To do this, they utilized brains from the VA-BU-CLF brain bank, since CTE can only be diagnosed after death. Specifically, the sample included 211 tackle football players who had been diagnosed with CTE and 35 who did not have CTE but many of whom frequently had other types of brain diseases. Dr. Alosco and the CTE Center research team conducted interviews with family members of the deceased players to obtain cognitive, psychological, and medical history, including the age of onset of any cognitive and behavioral or mood changes. In their analysis, the researchers found that the age of first exposure to tackle football was not associated with the severity of CTE pathology. However, the age of first exposure to football was significantly related to the onset of symptoms. Specifically, those who began tackle football before age 12 years had an earlier onset of cognitive, behavior, and mood symptoms by an average of 13 years. Every one year younger that the individuals began to play tackle football predicted earlier onset of cognitive problems by 2.4 years and behavioral and mood problems by 2.5 years. These findings were again independent of the total number of years of football played. Findings suggested that starting to play tackle football at a younger age, particularly before age 12 years, may lead to earlier onset of cognitive and emotional symptoms among athletes who were diagnosed with CTE and other brain diseases after death.

Similar studies (McKee et al. 2009; Bieniek et al. 2015; Ling et al. 2017) done by researchers around the country have found evidence of CTE in players of other contact and collision sports, like soccer and hockey. In these sports, the repeated hits to the head that can occur in specific positions may have long-term consequences.

Much more research is needed to better understand the development of CTE over time, and how the age of first exposure to contact sports may affect long-term cognitive function. In the future, Dr. Alosco and the CTE Center research team are hoping to launch studies that track players over time, from the time they first start playing a sport until later on in life. These studies take many years to complete, but they will provide a better picture of the relationship between contact sports, repeated hits to the head, age of first exposure to each sport, and the development and progression of CTE. In addition, Dr. Alosco and his colleagues are actively searching for risk factors and biomarkers of CTE that would allow for a diagnosis of the disease before death, potentially opening up treatment options.

Dr. Michael Alosco is an Assistant Professor of Neurology at Boston University where he works with the Boston University Alzheimer’s Disease Center and CTE Center. Dr. Alosco is a clinical neuropsychologist specializing in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and CTE. When not in the laboratory, Dr. Alosco enjoys spending time with his family, running, and golfing.

For More Information:

- Alosco, M. et al. 2018. “Age of first exposure to tackle football and chronic traumatic encephalopathy.” Annals of Neurology, 83: 886-901.

- Alosco, M. et al. 2017. “Age of first exposure to American football and long-term neuropsychiatric and cognitive outcomes.” Translational Psychiatry, 7: 1-8.

- Mez, J. et al. 2017. “Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of American football.” Journal of the American Medical Association, 318(4): 360-370.

- Ling H, et al. 2017. “Mixed pathologies including chronic traumatic encephalopathy account for dementia in retired association football (soccer) players.” Acta Neuropathologica, 133:337-352.

- Alosco, M. et al. 2016. “Repetitive head impact exposure and later-life plasma total tau in former National Football League players.” Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 7:33-40.

- McKee AC, et al. 2016. “The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy.” Acta Neuropathologica, 131:75–86.

- Bahrami N, et al. 2016. “Subconcussive head impact exposure and white matter tract changes over a single season of youth football.” Radiology, 281:919-926.

- Stamm, J. et al. 2015. “Age of first exposure to football and later-life cognitive impairment in former NFL players.” Neurology, 84: 1114-1119.

- Bieniek KF, et al. 2015. “Chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology in a neurodegenerative disorders brain bank." Acta Neuropathologica,130:877-89.

- McKee AC, et al. 2009. “Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury.” Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 68:709-735.

To Learn More:

- Boston University CTE Center. https://www.bu.edu/cte/

- Concussion Legacy Foundation. https://concussionfoundation.org/CTE-resources/what-is-CTE

- Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chronic-traumatic-encephalopathy/symptoms-causes/syc-20370921

- Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/related_conditions/chronic-traumatic-encephalopathy-(cte)

- HEADS UP at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/index.html and https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/CDC-CTE-ProvidersFactSheet-508.pdf

- Three brains in one. http://psycheducation.org/brain-tours/3-brains-in-one-brain/

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |

|

|

Dr. Mike Alosco

Dr. Jesse Mez

Dr. Ann McKee

Dr. Robert Stern

Pictures From: BU CTE Center website, http://www.bu.edu/cte/about/

Sign Up for our Monthly Announcement!

...or  subscribe to all of our stories! subscribe to all of our stories!

What A Year! is a project of the Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research.

|

|