|

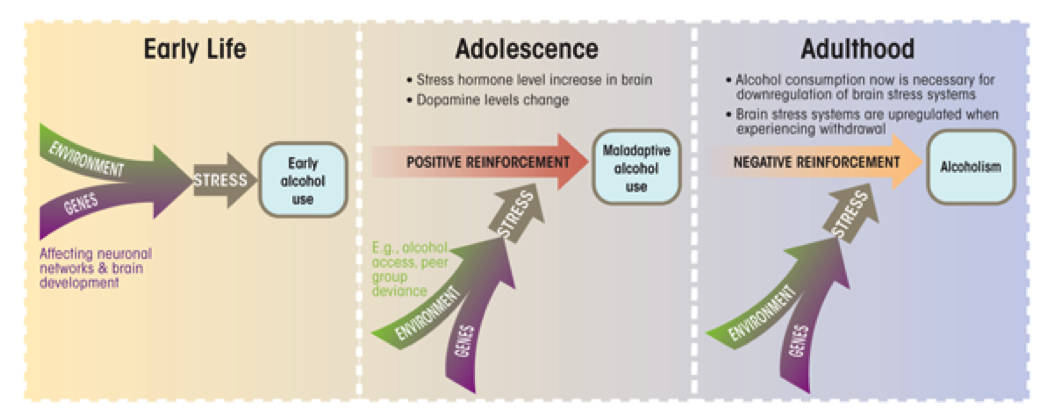

Although federal law prohibits the consumption of alcohol by anyone under the age of twenty-one, adolescents and young adults sometimes choose to drink. According to the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,

22.7 percent of adolescents between the ages of 12 and 20 reported drinking alcohol.

You have likely learned about the risks of alcohol at home or in school. It is important to understand these risks now because the consequences can be long-lasting. Research has shown that

regular alcohol use during the teenage years can increase the risk of alcohol dependency later in life.

Alcohol dependence and alcoholism, known by researchers as

alcohol use disorders or AUDs,

are our focus this month.

Source: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov

Alcohol Use and Abuse

AUDs (Alcohol Use Disorders), like other substance abuse disorders, are considered to be a form of

mental illness.

They are categorized ranging from mild to severe based on eleven criteria developed by the American Psychiatric Association. These criteria include cravings for alcohol; drinking alcohol more than you intend or want to; problems with family or friends as a result of drinking; and trouble at school or work

as a result of drinking.

The development of alcoholism is complex, likely involving a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental influence. So treatment options are multifaceted and must be personalized. Treatments for AUDs range from peer support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous and individual and group therapy to hospital-based residential treatment centers and medication-assisted treatments. More information about alcohol, alcohol abuse, and treatments for AUDs can be found in the links provided in the "To Learn More" section at the end of this article.

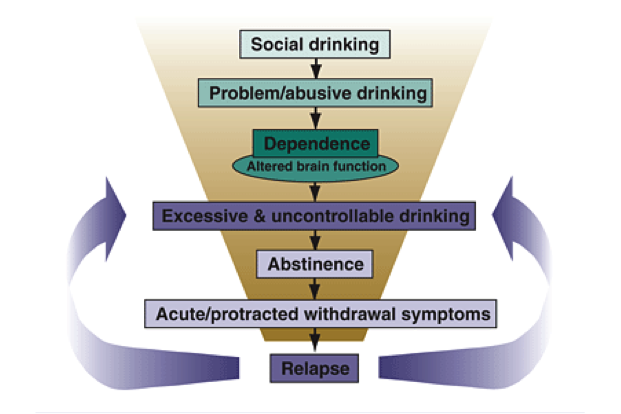

Despite ongoing treatment, people with AUDs may experience periods of relapse, characterized by a return to drug use. Specific triggers for relapse behavior vary greatly from person to person but include stress, exposure to environmental cues associated with use, and exposure to the drug itself.

AUDs as well as other substance abuse disorders are considered chronic because the tendency to think about or want drugs is always present. Despite ongoing treatment, people with AUDs may experience periods of relapse, characterized by a return to drug use.

Specific triggers for relapse behavior vary greatly from person to person but include stress, exposure to environmental cues associated with use, and exposure to the drug itself.

Stress triggers are strong emotions or traumatic events that cause a person to crave alcohol. Environmental triggers refer to familiar sights and sounds that remind the person of times when they used to drink. Exposure triggers refer to brief drug-use lapses, such as social drinking situations, where a person may think "just one drink won't hurt me". People may react more or less strongly to different triggers. Individuals needs to figure out what factors trigger a

relapse

for them, so they can be avoided. Relapse prevention is a critical component of any AUD treatment plan.

Source: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov

Men, Women and Alcohol

In recent decades, more and more women have joined their male counterparts in recreational drug and alcohol use. Many more women have developed AUDs. Amongst the adolescent population (12-17 years), 385,000 females and 311,000 males were diagnosed with an AUD in 2013.

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 16.6 million American adults over age 18 (seven percent of the population) were diagnosed with an AUD in 2013.

This included 10.8 million men (9.4% of the male population) and 5.8 million women (4.7% of the female population).

As these numbers indicate, the adult population with AUDs contains nearly twice as many men as women. Indeed, drug and alcohol use and abuse are still commonly considered to be largely a man's problem. Until the 1970s, men were the primary consumers of drugs and alcohol, and also their primary abusers. As a result, most of the established treatments for AUDs have been developed for men.

In recent decades, as more and more women have joined their male counterparts in recreational drug and alcohol use, many more women have developed AUDs. Amongst the adolescent population (12-17 years), 385,000 females and 311,000 males were diagnosed with an AUD in 2013.

These numbers represent 3.2% of adolescent females and 2.5% of adolescent males.

Although the ratio of males to females with AUDs in adolescence does not necessarily reflect what they will be in adulthood, the numbers indicate that the population of women with AUDs is growing, especially in the youngest group of alcohol users. The treatments offered to women with AUDs, though, reflect the needs of male patients and do not necessarily take into account differences between men and women with respect to external stressors and internal physiology. Drs. Mary Torregrossa and Megan Bertholomey want to change that.

Dr. Mary Torregrossa is an Assistant Professor of

Psychiatry

at the University of Pittsburgh and Dr. Megan Bertholomey is a postdoctoral fellow working with Dr. Torregrossa in her laboratory. Together they have completed a novel study comparing male-female differences with regards to alcohol drinking and seeking behavior. "There's a lot of anecdotal evidence from the human world and some data from the rodent world to suggest that males and females behave differently when it comes to alcohol consumption," explains Dr. Torregrossa. "However, variations in alcohol-related behavior as a function of sex are greatly understudied, and there is much we still need to learn about vulnerability to alcohol craving in females."

The Research

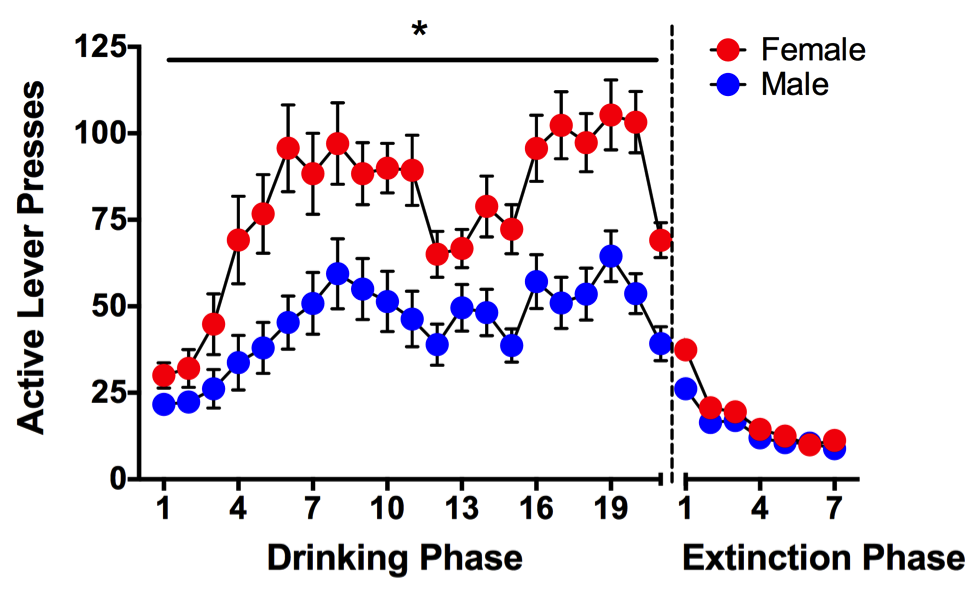

Drs. Torregrossa and Bertholomey used an established rodent model to study alcohol behavior. They studied males and females at the same time in order to compare male-female differences. The experimental protocol lasted about six weeks with three distinct phases designed to mirror the development of AUDs in humans: the drinking phase, the extinction phase, and the reinstatement phase.

Drinking Phase: To begin the drinking phase, the rats were taught to self-administer ethanol, the form of alcohol people consume, by pressing a lever accessible in a testing chamber. When the lever was pressed, the rats received ethanol as well as a light signal (visual cue) and tone (auditory cue) designed to create a familiar drinking environment for the rats. The lever was linked to a computerized data processing system that monitored how often it was pressed.

A rat in an operant box with the cue light on.

The drinking phase began at age 70 days, roughly the equivalent of college-age humans. The lever allowing access to ethanol was available for one hour every day for twenty days. During this time, the researchers recorded the number of times the lever was pressed by male and female rats (in separate chambers) and the amount of ethanol consumed. By the end of the drinking phase, the rats exhibited substantial ethanol-motivated behavior, actively consuming large quantities in the allotted one-hour window.

Extinction Phase: Once the rats had successfully acquired stable ethanol drinking, they underwent approximately seven additional sessions that were exactly the same, but lacked either ethanol or audiovisual cues. This is known as the extinction phase because the lever-pressing behavior that used to give the rats ethanol is extinguished. This phase models periods of abstinence in people with AUDs.

For the first few sessions, the rats continued to press the lever in the hopes of receiving ethanol, although this behavior did not result in either audiovisual cues or ethanol. Over time, the rats learned that lever pressing no longer resulted in the delivery of ethanol and stopped pressing it so frequently. The extinction phase ended when the rats no longer showed interest in the lever, defined as less than twenty responses over two days. The typical extinction phase lasted about one week.

Key Observation: In the first two phases of this experiment, Drs. Torregrossa and Bertholomey made a key observation: they found that female rats consistently drank more ethanol than their male counterparts during any one-hour session. Although the female rats tended to drink more, they exhibited the same behaviors as the male rats in the extinction phase. Despite the increased drinking, they were able to stop just as quickly.

This graph shows active lever presses during the drinking and extinction phases. The * symbol shows that female rats responded more for ethanol than male rats in the drinking phase. However, females quickly dropped to male levels of responding in the extinction phase.

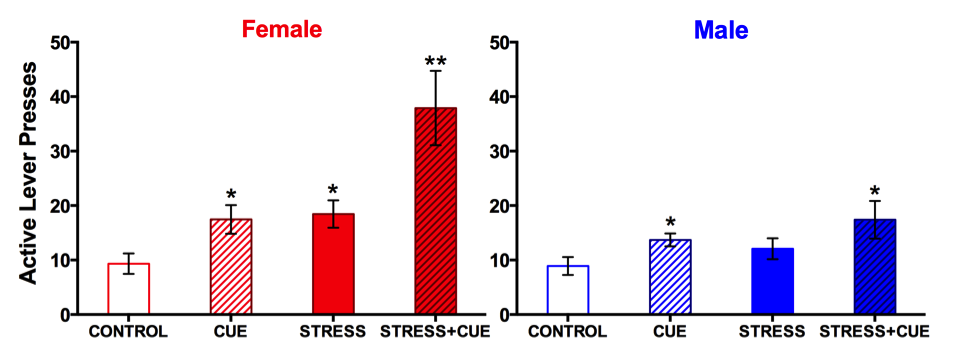

Reinstatement Phase: The third and final phase of the experimental protocol began as soon as the extinction phase ended. This is known as the reinstatement phase because stimuli are introduced into the environment that can lead to the reinstatement of the lever pressing behavior, even though the rats are still not receiving ethanol. This happens because even though the rats have learned that lever pressing is no longer resulting in access to ethanol, certain stimuli can trigger memories of ethanol drinking, causing a craving-like response. Similar types of stimuli have the potential to increase the risk of relapse in humans with AUDs attempting to maintain abstinence.

The researchers divided the rats into four groups of different combinations of stimuli. In the control group, rats had no exposure to any stimuli, and their session was identical to the extinction sessions. The second group was the CUE group, in which the rats received the audiovisual cues. In the final two experimental groups, the rats were injected with the drug yohimbine 10 minutes prior to beginning the reinstatement session. Yohimbine induces a stress response in rats by stimulating a series of chemical signals in the body that leads to the release of the hormone corticosterone, similar to the stress hormone

cortisol

in humans. The STRESS experimental group was given yohimbine alone; the STRESS + CUE group was given yohimbine as well as the audiovisual cues. Both groups of male and female rats received each of these treatments in random order.

During the reinstatement phase, each group of rats was allowed to press the lever for a single one-hour session, as in the extinction phase of the experiment, except that they were exposed to the craving-inducing stimuli. Their behavior was observed during this time. Each reinstatement session was followed by 2-3 extinction sessions to ensure that extinction criteria were met before re-testing.

This graph shows active lever presses during a reinstatement test in male and female rats exposed to various stimuli (listed below the bars) after their ethanol-motivated behavior had been extinguished. The * symbol shows that rats in that group pressed significantly more than the control group, while the ** symbol shows that rats in the group pressed significantly more than the other treatment groups. Female rats showed higher active lever presses following cue and stress exposure separately, and even greater presses following STRESS + CUE exposure together. In contrast, males only showed higher active lever presses following cue exposure, and to a lesser degree than the females.

Relapsing Rats

How did the rats respond to these stimuli? Drs. Torregrossa and Bertholomey observed that the control rats-both males and females-maintained low levels of lever pressing similar to what was exhibited during the extinction phase. Without exposure to the stress-inducing drug or to the audiovisual cue that was previously associated with ethanol, they hardly pressed the lever.

Recovering alcoholics are constantly exposed to external cues that remind them of the times when they used to drink: familiar sights and sounds, familiar bars, restaurants, or other environments-these are all huge factors that cause craving in recovering alcoholics which can lead to relapse.

But this is not the world we live in. Recovering alcoholics are constantly exposed to external cues that remind them of the times when they used to drink: familiar sights and sounds, familiar bars, restaurants, or other environments - these are all huge factors that cause craving in recovering alcoholics which can lead to relapse. Indeed, the researchers observed that when rats were presented with the audiovisual cues, they were more likely to show ethanol-craving behavior. This was true for both males and females.

Stress is another common relapse trigger for recovering alcoholics. This was the point in the study where the male and female rats began to respond differently. The researchers observed that female STRESS rats immediately began to press the lever that used to result in ethanol delivery, showing a robust reinstatement response. The male STRESS rats showed no such response.

The results were even more pronounced for the STRESS + CUE rats that were feeling stressed while being exposed to the cues associated with drinking. In this group (STRESS + CUE), female rats pressed more than twice as much as male rats with the same treatment, showing a much greater craving response.

The researchers were not surprised by their results. "We know that men and women respond differently to stress and that women are, in general, more vulnerable," explains Dr. Torregrossa. "We also know from previous studies of rat behavior and cocaine use that female rats are more susceptible to addictive behaviors when exposed to stress."

With this study, Drs. Torregrossa and Bertholomey provided scientific evidence that female rats who drink significant amounts of alcohol are more vulnerable to relapse when exposed to stress, especially in the presence of alcohol-paired cues. We can hypothesize, then, that the same might be true for women recovering from AUDs. "We hope that our findings in female rats can inform treatment and support for alcohol-dependent women," adds Dr. Bertholomey. "That is one of our goals."

Research on Alcohol and Adolescence

Drs. Torregrossa and Bertholomey continued their research to investigate the relationship between stress and alcohol in follow-up experiments. There is a large body of evidence from both the human and animal worlds that exposure to stress during adolescence can increase the risk for alcohol dependency. To test this hypothesis in rats, the researchers conducted a second study with an additional stressor phase from ages day 30 to 50. This is about the equivalent of ages ten to sixteen years in humans.

During the stressor phase, the adolescent rats were given corticosterone, the rat stress hormone, in their drinking water. The rats were then left alone between ages day 50 and 70, when the ethanol drinking phase began. Once again, female rats drank much more ethanol than male rats, replicating the findings of the previous experiment. In addition, female rats exposed to chronic stress in adolescence showed even greater drinking than non-stressed females. In the reinstatement phase, which used similar methods as the previous experiment, the effects of adolescent stress were remarkable. "The female rats were much more sensitive to yohimbine in producing the craving response than the males," explains Dr. Bertholomey. "And female rats exposed to adolescent stress in particular showed higher craving responses after exposure to the audiovisual cue."

In their research, Drs. Torregrossa and Bertholomey have taken a valuable step in a growing field of research into the relationship between stress and alcohol use, with particular attention to male-female differences. Future work will investigate brain pathways that drive these behaviors and include

stress hormones,

estrogen

and

gonadal hormones

and the

dopamine

system. Some of these pathways between stress and alcohol drinking have been mapped out for other drugs-but only in males. The researchers plan to do complementary research for females.

Such research would monitor brain function during these experiments to identify what parts of the brain are most active in each part of the experiment. At the end of the experiment, brain tissue would be studied to identify molecular and genetic markers for further research. The influence of sex hormone cycles is also an important area for further research. "It's a very exciting time," comments Dr. Bertholomey. "Ultimately our goal is to help more people get better by developing more effective treatments for AUDs," concludes Dr. Torregrossa. "This is one step in the right direction."

Lessons to highlight from this research are 1) there are real differences between men in women with regards to alcohol use (how many drinks you have) and behavior (the factors that drive you to drink or crave alcohol) and 2) adolescence is a defining time in our lives and brain development, which means that traumatic events or stressful environments during these years can shape how we respond to drugs and alcohol in the future. Consider this before use.

There are two important lessons from this research for current adolescents, especially as you begin to be exposed to drugs and alcohol. First, be aware that there are real differences between men in women with regards to alcohol use and behavior. This is not just in terms of the number of drinks you can tolerate, but in the external and internal factors that drive you to drink or crave alcohol in the first place. A second, related message is that adolescence is a defining time in our lives and our brain development. Traumatic events or stressful environments during these formative years can shape how we respond to drugs and alcohol in the future. It is worth considering that response now-before use.

Dr. Torregrossa is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. When not in the laboratory, she enjoys spending time with her family and two young children.

Dr. Bertholomey is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Dr. Torregrossa?s laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh. When not in the lab she enjoys craft beer, music, festivals, good food, seeing her friends and exploring the art and culture in Pittsburgh.

For More Information:

- Bertholomey, M. and M. Torregrossa. 2015. "Female rats are more sensitive to enhanced reinstatement of alcohol following exposure to both alcohol related cues and yohimbine." FASEB J, 29:1Suppl 1019.8 http://www.fasebj.org/content/29/1_Supplement/1019.8.abstract?sid=2477

- Torregrossa, M., M. Xie, and J. Taylor. 2012. "Chronic corticosterone exposure during adolescence reduces impulsive action but increases impulsive choice and sensitivity to yohimbine in male Sprague-Dawley rats." Neuropsychopharmachology, 37: 1656-70.

- Feltenstein, M., A. Henderson, and R. See. 2011. "Enhancement of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by yohimbine: sex differences and the role of the estrous cycle." Psychopharmacology, 216: 53-62.

To Learn More:

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-use-disorders

http://rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/WhatsTheHarm/WhatAreSymptomsOfAnAlcoholUseDisorder.asp

- American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/alcohol-disorders.aspx

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. https://ncadd.org/learn-about-alcohol/overview

- Recovery.org. http://www.recovery.org/topics/alcohol-and-drug-addiction-recovery/

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |