| |

Stress can be brought on by any physiological or environmental disturbance that disrupts our physical or mental balance. Stress can be a good thing, keeping us motivated and energized, as in stress from sports or mental activities like completing school projects under short deadlines.

Every person’s body responds to stress in different ways, but we all share a classic stress response characterized by (1) increased blood pressure, (2) tense muscles, (3) reduced sensitivity to pain and (4) reduced appetite. You may also experience difficulty sleeping or mood changes. These symptoms occur as the result of increased levels of stress

hormones

produced by the

adrenal glands

, part of the

endocrine system

located above the kidneys.

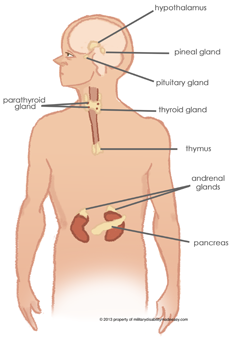

The endocrine system. Note the adrenal glands above the kidneys.

The Endocrine System.

Usually, once the disturbance that caused the stress ends, the body returns to equilibrium and the symptoms of stress subside. Sometimes, however, the stress does not let up. In cases of prolonged stress, these physiological changes can actually become permanent. That results in a variety of adverse consequences including reduced

immune

function and mental illness. For example, the battlefield is one of the most stressful places on earth, and soldiers often return with physiological changes that affect their physical and mental health. Similarly, in space it is well documented that astronauts return to earth with compromised immune systems.

In cases of prolonged stress, these physiological changes can actually become permanent, resulting in a variety of adverse consequences including reduced immune function and mental illness.

Yet in both cases, the connections between external stress and the physiological changes that accompany them are often unclear. New research by Dr. Rasha Hammamieh and a team of scientists at the U.S. Army Center for Environmental Health Research has jump-started our understanding of stress and its consequences—both on earth and in space. These findings could have important implications for anyone familiar with stress.

Ranger Training … Not For The Fainthearted

The first part of the study began some years ago with research assessing immune function under battlefield-like conditions. The research included soldiers participating in the army ranger training program known as Ranger Assessment and Selection Program, or RASP for short. This is an incredibly challenging program: soldiers experience hunger, sleep deprivation and a variety of other physical and mental stressors in preparation for their deployment. The research team took blood samples from thirty soldiers before they started the program, and again after completion. The before and after blood samples were searched for specific genes that might have been expressed differently as a result of this stressful experience. Complex computer programs allowed the researchers to examine gene and protein expression across the entire

genome

in the same experiment.

Army Rangers

“Hunting for genes can be like looking for a needle in a haystack,” explains Dr. Marti Jett, Director of the Integrative Systems Biology Program at the U.S. Army Center for Environmental Health Research. That’s because each cell in the human body contains tens of thousands of genes. Quantifying the expression of that many genes would have been an unthinkable task even a decade ago. It is now possible with the development of complex computer programs. These programs generate an enormous amount of data that researchers sift through to find meaning. The researchers found that 1,400 genes associated with the immune response were much less expressed after RASP than before.

These results provide further evidence that prolonged stress affects the immune system by altering the expression of the genes involved. “How or why this happens still remains a mystery,” Dr. Jett remarks. Future research on earth will focus on how severe stress and the body’s responses to it can result in mental illnesses like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

And In Space

Astronaut Rex Walheim onboard the shuttle.

To further understand this connection between stress and the immune response, Dr. Hammamieh’s experiments were selected to be sent to space. In these experiments, the researchers challenged human cells with a bacterial pathogen and evaluated the ability of the cells to respond to this pathogen. The pathogen they chose was the toxin lipopolysaccharaide, or LPS, a common pathogen from the cell wall of some types of infectious bacteria. LPS activates the human immune system and stimulates the immune response. It also inhibits wound healing and, if left untreated, can cause severe sepsis.

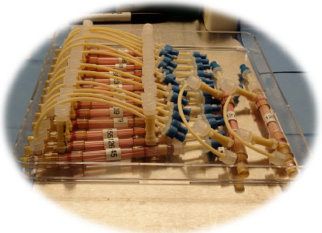

The cells were grown in a container called a bioreactor that was sent to space with four human astronauts on the Atlantis orbiter in 2011. The researchers had designed the experiment so it could be initiated by the astronauts simply by pressing a button on the bioreactor that would inject the pathogen into the cells. The exact same experiments were conducted both on earth and in space so the researchers could compare the results.

Bioreactors used to incubate the cells used in the experiment

Back On Earth … A Surprising Similarity

Once the Atlantis landed and the cells were back on earth, the researchers collected the samples and analyzed gene expression profiles in space compared to the ground. The aim of the study was to determine the effect of microgravity on host immune responses to the toxin. The researchers used the same computer programs as they had in previous experiments on the battlefield on earth. Surprisingly, their results were quite similar. Many of the same immune response genes that were significantly less expressed after the RASP were also significantly less expressed after the trip to space. These findings provide further evidence that the particular genes identified in these experiments in battle and in space play important roles in immune function and how it is affected by prolonged stress.

Dr. Marti Jett is Director of the Integrative Systems Biology Program at the U.S. Army Center for Environmental Health Research. The program takes a holistic, multidisciplinary approach to research. Their team includes biologists, chemists, biochemists, mathematicians, and engineers who work together to solve complex problems.

Dr. Rasha Hammamieh is the Deputy Director of the Integrative Systems Biology Program who led the research conducting experiments in space. Dr. Jett is an avid gardener who enjoys spending time with her family when not in the laboratory. Dr. Hammamieh is a soccer and basketball mom who spends her free time with her family, often watching her kids’ sports games.

To Learn More:

- Hammamieh, R. et al. 2012. "A Mouse Model of Social Defeat Stress Simulating Aspects of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder" Behavioural Brain Research, 235(1):55-66.

- Muhie, S. et al. 2012. “Transcriptome characterization of immune suppression from battlefield-like stress.” Genes and Immunity, p.1-16.

- Santos WJ, Waddy E, Chakraborty N, Gautam A, Hoke A, Jett M, Hammamieh R. Pan-omic Approaches to Study the Effect of Microgravity on Skin Endothelial Cells Submitted to Endotoxic Insult. The FASEB Journal. 2013;27:773.2.

- Valiyaveettil M, Alamneh YA, Miller SA, Hammamieh R, Arun P, Wang Y, Wei Y, Oguntayo S, Long JB, Nambiar MP. 2013. Modulation of cholinergic pathways and inflammatory mediators in blast-induced traumatic brain injury. Chem Biol Interact 203:371-375.

For More Information:

- Stress. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/stress.html

- McLeod SA. 2010. Stress and the Immune System - Simply Psychology. http://www.simplypsychology.org/stress-immune.html

- Space. http://www.nasa.gov/

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |

|

|

Left to right, top: Marti Jett, Aarti Gautam, Edward Waddy, William Santos, Allison Hoke and Stacy-Ann Miller. Bottom: Sima Marshall, Rasha Hammamieh and Nabarun Chakraborty

Amazing footage of Space Shuttle Atlantis on its final voyage.

Stephen Colbert interviews the crew of Atlantis, including Col. Rex Walheim.

Great Science Sites

NIH | High School

NIH | Middle School

ACS | Science for Kids

SciAm | Blog

Sign Up for our Monthly Announcement!

...or  subscribe to all of our stories! subscribe to all of our stories!

What A Year! is a project of the Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research.

|

|