| |

Highlights

- To understand the effects of heat therapy on obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), nine obese women with PCOS engaged in hot tub therapy for 8 to 10 weeks and eight obese women with PCOS served as controls.

- Data (height, weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, testosterone levels, vascular function, endothelial function, sympathetic nerve activity, fat biopsy) were collected at the beginning (0 weeks), middle (4-5 weeks), and end (8-10 weeks) of the study.

- The results showed that heat therapy had important effects for cardiovascular and metabolic health including decreases in cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood glucose levels; increased blood vessel function and resilience, decreased activity of the sympathetic nervous system, and decreased inflammation.

It's common knowledge that exercise is good for you. Exercise builds up the strength of your bones and your muscles, including your heart, and it increases the capacity of your lungs and other organs to function. As a result, exercise helps reduce

chronic diseases

such as

obesity,

diabetes,

and

high blood pressure,

to name a few. For many people, exercise is not an enjoyable activity; starting an exercise habit can be difficult and keeping it up even more so.

But what about people for whom exercise isn't a reasonable option? There are many people who might fit this category: anyone with physical injuries, limitations, or disabilities; people suffering from chronic pain; people for whom obesity makes it difficult to engage in regular, sustained physical activity. How might they engage in activity that increases the capacity of their heart and blood vessels to function and decrease the risk of

heart attack

and

stroke?

Brett Romano Ely, a doctoral student at the University of Oregon, along with her advisor Dr. Chris Minson had an idea: the hot tub, or, more formally,

heat therapy.

Dr. Brett Ely first became interested in human physiology as an athlete, a marathon runner who successfully qualified for four U.S. Olympic trials. "I wanted to know how to become a better athlete," Brett explained. "And I wanted to be part of research that can impact physical performance, and health—not just for athletes but for everyone." After receiving her master's degree in nutrition from James Madison University, Brett worked for several years at the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine in the Thermal Mountain and Medicine division, where she worked on projects looking at how heat and dehydration affect the body. Brett wanted to continue studying the effects of heat on the body for her doctorate research. Her advisor, Dr. Chris Minson at the University of Oregon, also had a longstanding interest in heat, and was additionally interested in

cardiovascular

health and women's health. Brett developed a research project that would combine all of these interests, looking at the effects of heat therapy on obese women with

polycystic ovary syndrome

or PCOS.

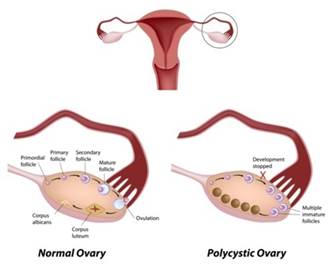

PCOS is an

endocrine

disorder thought to be caused by a variety of factors. One of these factors is over-activity of the

sympathetic nervous system,

the system responsible for our "fight or flight" response in times of stress. PCOS is characterized by irregular periods, elevated levels of

testosterone,

and

polycystic ovaries.

Polycystic ovaries are typically enlarged and may contain

cysts.

They can interfere with regular menstrual function, which is why PCOS is associated with irregular periods. About 15% of women in the U.S. live with PCOS.

Figure 1. Picture of normal and polycystic ovary.

[Source: National Library of Medicine (US). Genetics Home Reference [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): The Library; 2013 Sep 16. [Illustration] Polycystic Ovary Syndrome; [cited 2013 Sep 19]. Available from: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/polycystic-ovary-syndrome.]

In obese women, these symptoms can be more severe. The statistics vary, but studies report that 50 to 80% of women with PCOS are obese. This is because the condition is associated with

insulin resistance

and other

metabolic abnormalities

that make it more likely for women who develop PCOS to be obese. Obesity exacerbates the symptoms of PCOS, which makes it more difficult to exercise and take part in other activities that could improve their health.

At the outset of this research project, Brett spoke with many obese women with PCOS who had negative experiences with medical treatment. Some went to the doctor to be treated for this condition and were simply told to lose weight without being offered any other treatment options. "A lot of the women I talked to had experiences with doctors who told them that PCOS was their fault," recalled Brett. "Given how common this condition is and how limited the treatment options were, I wanted to find a different approach."

Heat therapy is a relatively new field of science and medicine that has developed over the past two decades. The purpose is to use heat—such as a hot tub, sauna, or steam bath—to improve different health outcomes. Small initial studies in humans have been successful at using heat therapy to control

blood sugar

levels (Hooper, 1999) and improve blood vessel function (Brunt et al. 2016). These

clinical trials

are supported by evidence from previous studies in animals that demonstrate the effects of heat therapy on cardiovascular health (Horowitz, 2002).

In the study Brett developed, nine obese women with PCOS engaged in 30 hours of hot tub therapy over the course of 8-10 weeks, while another eight obese women with PCOS served as time controls and did not undergo heat therapy. The average age of participants was 26 years. The women submerged themselves in the hot tub set at 104.5 degrees Fahrenheit for one-hour sessions in which they relaxed, listened to podcasts, or watched TV. Brett, along with a large team of fellow graduate students and undergraduate research assistants, made sure the participants were well hydrated, and their heart rate and body temperature were monitored throughout the exposure.

To understand how heat therapy would impact the participants, Brett took a variety of samples and measurements at the beginning (0 weeks), middle (4-5 weeks), and end (8-10 weeks) of the study. At each time point, the participants came into the laboratory for measurement of height, weight, and blood pressure. Blood samples were taken to measure

cholesterol,

sugar, and testosterone levels. In addition, the following four tests were performed:

-

Oral

glucose

tolerance test. All participants (n=17) took part in this test to see whether their glucose tolerance improved over time. Participants fasted for 12 hours, then drank a glucose beverage. Their blood glucose and insulin were monitored for 2 hours. This test is often given to pregnant women to test for gestational diabetes, or to people suspected of developing type 2 diabetes.

Figure 2. Brett Ely using ultrasound to take images of blood vessels to measure wall thickness.

Photo courtesy of Damian Foley.

-

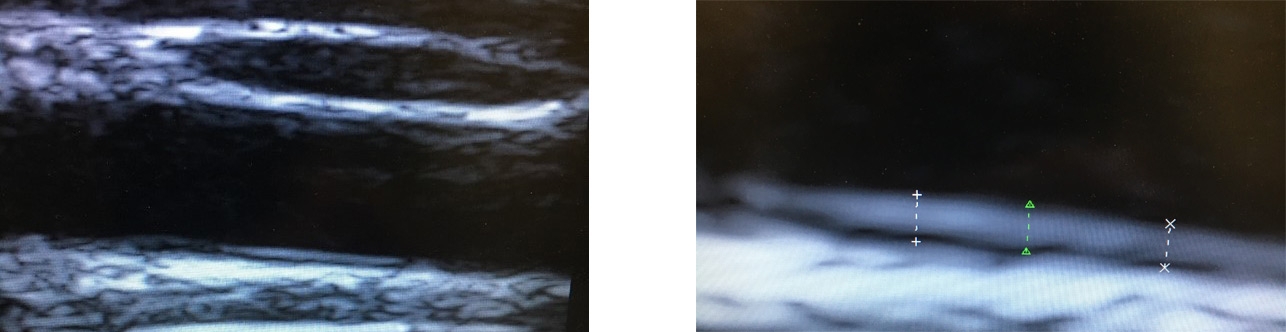

Vascular

function study. Brett used

ultrasound

(the same technique used to take images of babies in the womb) to image the blood vessels of the participants at the beginning, middle, and end of the study to measure the thickness of the inner two layers of blood vessels, called

intima media thickness.

Thicker lining indicates mineral and fat deposits that can contribute to heart disease and other conditions. Brett wanted to measure whether the thickness of the blood vessel lining changed over the course of the study.

Figure 3. Ultrasound image of the carotid artery (left), zoomed in to measure wall thickness (right). Photo courtesy of Brett Ely.

-

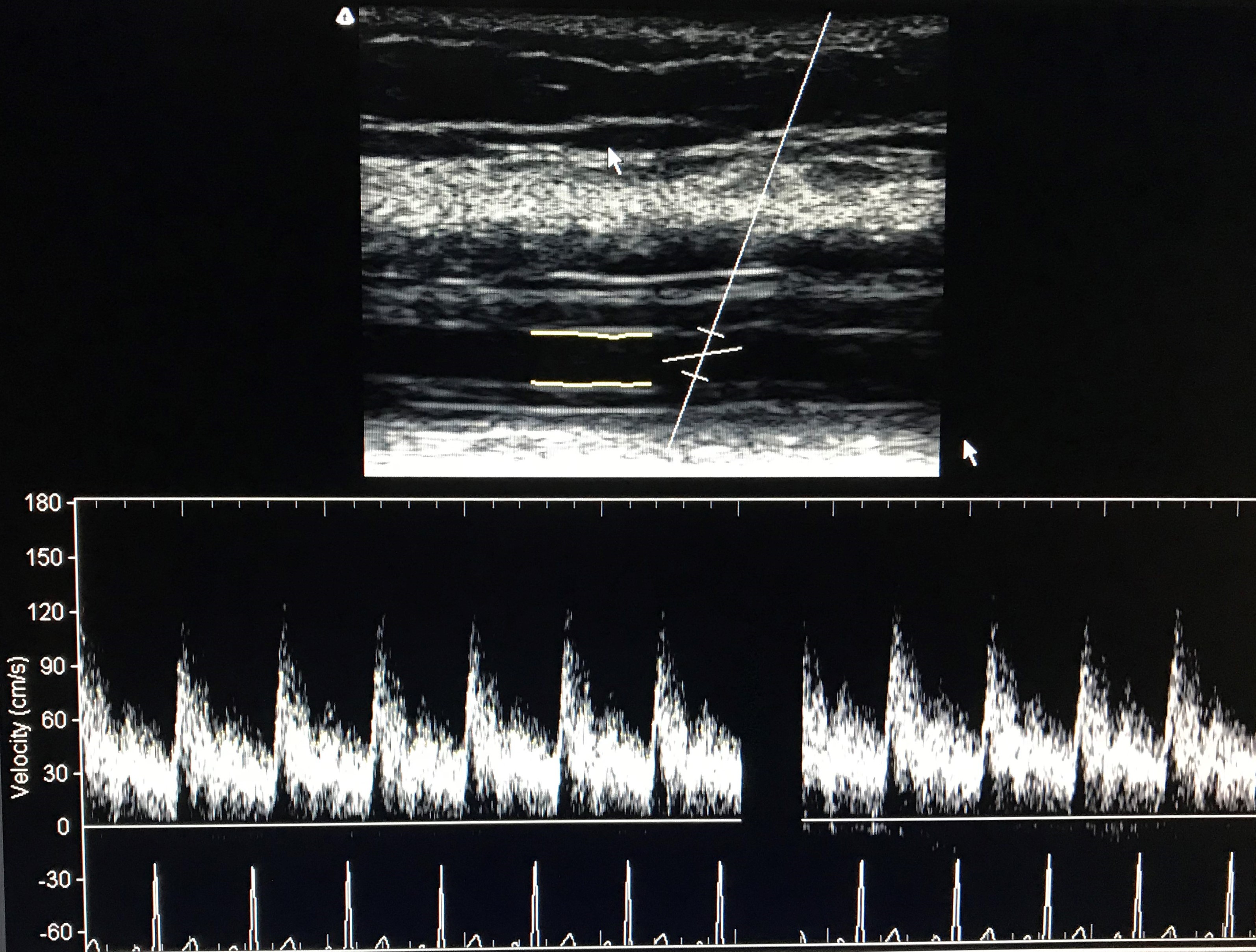

Endothelial function study. Brett also wanted to understand how the ability of the participants' blood vessels to adapt to stress changed over time. Women with PCOS are at higher risk of dying due to heart attack or stroke. There was no way to measure the likelihood of such events in this study, but one substitute test is to see how the blood vessels respond to stress. This is done by temporarily blocking one of the blood vessels on the arm and seeing how the blood vessel responds.

Figure 4. Ultrasound image of the brachial artery during an endothelial function study. Blood vessels respond to changes in blood flow by increasing or decreasing diameter, which can be measured with ultrasound. Photo courtesy of Brett Ely.

-

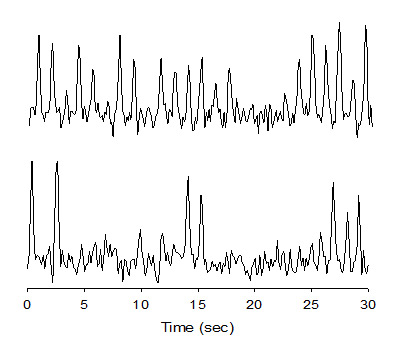

Muscle sympathetic nerve activity. In people with obesity and women with PCOS, the sympathetic nervous system is overactive. This is part of the reason that both of these conditions elevate the risk for cardiovascular disease. Sympathetic nervous system activity can be observed directly by inserting a tiny

microelectrode,

like a small needle, into the nerve that runs behind the knee. The microelectrode records the electrical activity of the nerve and can measure how active it is.

Figure 5. Brett placing an electrode to record nerve activity. Since the electrical activity of the nerve is being measured, electrical noise from lights can interfere, so this technique is done in the dark using a headlamp. Photo courtesy of Damian Foley.

In addition, a

subcutaneous fat

biopsy

was taken at the beginning and end of the study. During this procedure, a small amount of tissue was taken from the abdominal region to test for different markers related to

inflammation.

Brett wanted to know how these markers changed over the course of the study to understand what cellular changes might be driving the changes observed over the course of treatment.

After analyzing all the results, Brett had some remarkable findings:

Blood pressure and fasting sugar levels dropped significantly from the elevated range to the normal range. Cholesterol levels and markers of inflammation in the blood also dropped over the course of the study. Eight of nine subjects who underwent heat therapy changed risk category: from pre-diabetic or impaired to normal blood glucose response. Arterial stiffness decreased, indicating improved cardiovascular health. Endothelial function increased, suggesting that if a participant had a heart attack or stroke she would be more likely to survive it. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity decreased by 40%. -

In addition, more than half of participants reported that they had resumed normal menstrual cycles. Recall that irregular periods is a common symptom of PCOS, so the fact that periods resumed normally shows that heat therapy significantly improved the condition. Testosterone levels also decreased, another indication that heat may have impacted PCOS symptomology.

Figure 6. Example nerve recordings at the beginning (top) and end (bottom) of the study. Sharp deflections represent nerve 'bursts', and lower burst activity represents a healthier cardiovascular profile. Photo courtesy of Brett Ely.

To better understand these results, Brett turned to the subcutaneous tissue samples taken at the beginning and end of the study. She compared the levels of different markers of inflammation and insulin signaling between the samples from the beginning of the study with those taken at the end of the study. The results showed significant increases in insulin signaling markers and decreases in inflammatory markers in post-study tissue samples compared with pre-tissue samples.

Based on these preliminary findings, Brett concluded that heat therapy had important effects for cardiovascular and metabolic health including decreased cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood glucose levels; increased blood vessel function and resilience, and decreased activity of the sympathetic nervous system along with decreased inflammation. Importantly for these women who also had PCOS, menstrual activity resumed and testosterone levels decreased.

It is still unclear how long these results will last after the end of the study period. Brett has heard from participants that they maintained regular menstrual cycles for up to a year after the treatment finished. However, the participants have not returned to the laboratory so there is no way to know their current response. In future research, Brett plans to conduct longer studies that will gather data over longer periods of time. Brett hypothesizes that after an intensive 8-week treatment where participants went to the hot tub 3-4 times per week, they may only need to continue 1-2 times per week to maintain their initial gains.

Does this mean that hanging out in the hot tub can replace exercise? "Absolutely not," cautioned Brett. "Heat therapy and exercise are two separate things." Exercise has a significant benefit of calorie burn and potential weight loss that hot tub bathing does not. On the other hand, heat therapy reduced blood pressure by an average of 10 mmHg. In most exercise studies, blood pressure reductions are on the order of 3-5 mmHg. Heat therapy might offer some additional or added benefits to a regular exercise schedule.

This is why Brett suggests that heat therapy and exercise can complement one another. For example, sustained regular exercise was not possible for many of the participants in the heat therapy study due to limitations caused by excess weight or low fitness. Over time, though, heat therapy might be able to ease the transition into exercise as the participants build their cardiovascular capacity. A participant might walk for 10 minutes and then stay in the hot tub for 50 minutes. Over time, walking can increase and heat therapy can decrease, so they are walking 50 minutes and bathing 10 minutes.

Another application of this research in Dr. Minson's lab is seen with patients recovering from spinal cord injuries. People with spinal cord injuries can't get the benefits of exercise due to mobility limitations, but they can still see health improvements through heat therapy. Moreover, research into elite athletes has shown that heat acclimation can improve their performance (Lorenzo et al. 2010). "I don't see exercise and heat in competition with one another," concludes Brett. "I see them as both important ways to work towards improved health." In future work, Brett plans to explore how combining heat therapy and exercise would work in practice.

Brett Romano Ely conducted this work for her doctoral degree on the topic of heat therapy for obese women with PCOS between 2012 and 2018 at University of Oregon in the Department of Human Physiology. Her advisor was Dr. Chris Minson, the Singer Endowed Professor of Human Physiology at the University of Oregon. Brett received her doctorate in 2018 and has accepted a position as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sport and Movement Science at Salem State University in Salem, MA. Dr. Ely became interested in human physiology as a way to improve her own athletic performance as a marathon runner, and she continues to enjoy running when not working in the laboratory. In addition, Dr. Ely enjoys cooking and baking, hiking, camping, and being active and outdoors.

For More Information:

- Ely, BR. et al. "Heat Therapy Decreases Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Improves Insulin Signaling in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome." 2018. https://www.fasebj.org/doi/abs/10.1096/fasebj.2018.32.1_supplement.853.10

- Ely, B. et al. 2018. "Meta-inflammation and cardiometabolic disease in obesity: Can heat therapy help?" Temperature, 5(1): 9-21.

- Brunt, V.E. et al. 2016. "Passive heat therapy improves endothelial function, arterial stiffness and blood pressure in sedentary humans." Journal of Physiology, 594:5329-5342. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1113/JP272453

- Lorenzo, S. et al. 2010. "Heat acclimation improves exercise performance." Journal of Applied Physiology, 109:1140-1147.

- Horowitz, M. 2002. "From molecular and cellular to integrative heat defense during exposure to chronic heat." Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular and Integrative Physiology, 131:475-483.

- Hooper, PL. 1999. "Hot-tub therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus." New England Journal of Medicine, 341:924-925.

To Learn More:

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

- U.S. Office of Women's Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/polycystic-ovary-syndrome

- National Women's Health Network. https://nwhn.org/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos/

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMHT0024506/

- "When Missed Periods are a Metabolic Problem." https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/06/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos/396116/

Obesity

- American Heart Association. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/WeightManagement/Obesity/Obesity-Information_UCM_307908_Article.jsp#.W0Kxq6dKg2w

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/

- World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/obesity/en/

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |

|

|

Brett Ely, Chris Minson, and Samantha Bryan after receiving awards at the 2017 ACSM Northwest conference for their work on heat therapy and PCOS.

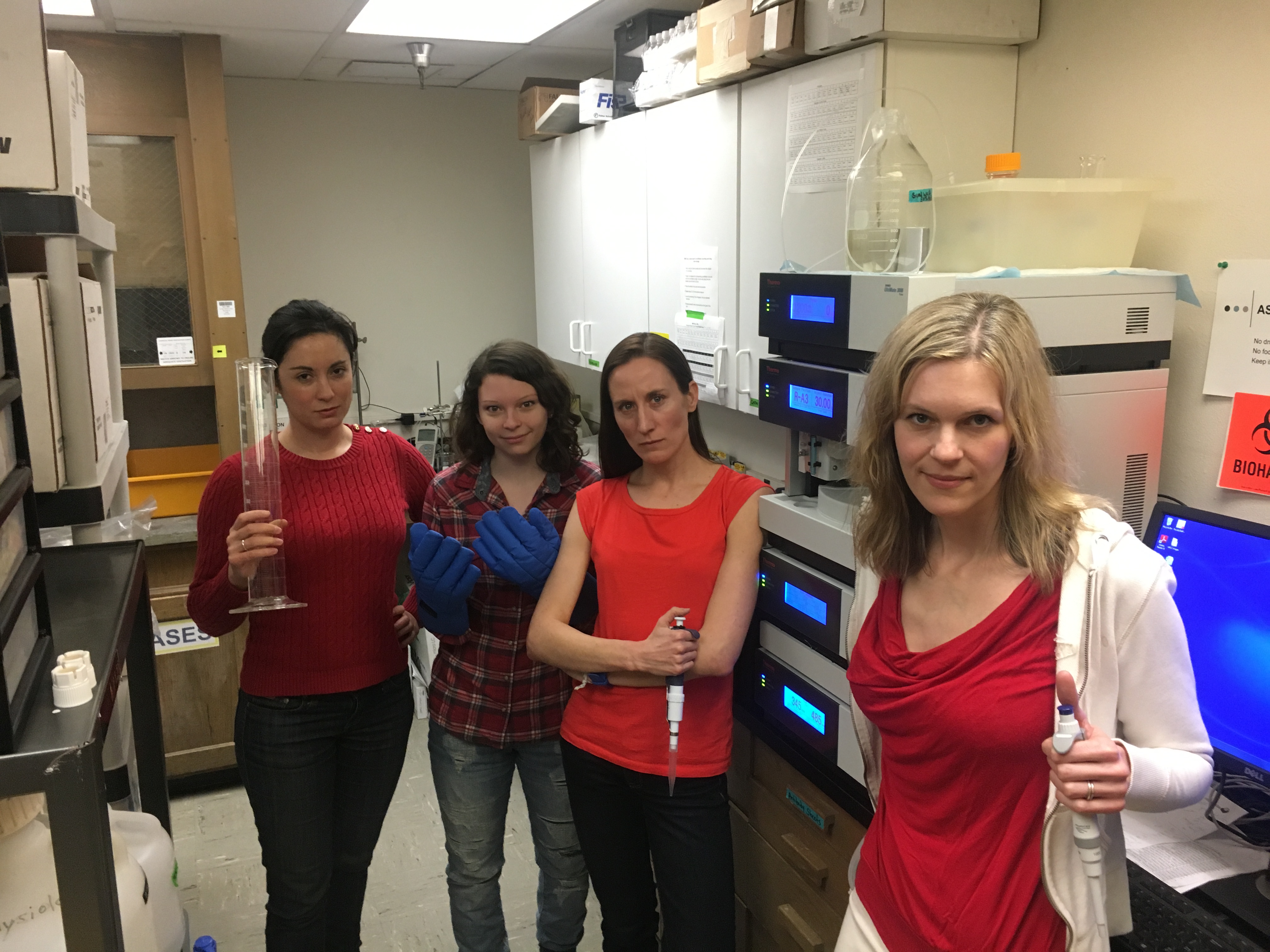

Elise Wright, Emily Larson, Brett Ely, and Karen Needham on International Womens' Day.

Brett Ely running the 2016 U.S. Olympic Team Trials Marathon. Photo courtesy of Saltyrunning.com.

Minson Lab at 2017 ACSM Northwest conference. From left: Samantha Bryan, Brett Ely, Michael Francisco, Lindy Comrada, Chris Minson, Elise Wright, Emily Larson, Cameron Colbert.

Minson Lab at the ACSM Northwest conference, 2015. Top, from left: Michael Francisco, Jared Steele, Andrew Jeckell, Chris Minson. Middle: Lindy Comrada, Brett Ely, Vienna Brunt, Taylor Eymann. Bottom row: Kaitlin Livingston, Matthew Howard.

Sign Up for our Monthly Announcement!

...or  subscribe to all of our stories! subscribe to all of our stories!

What A Year! is a project of the Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research.

|

|