How many students in your class regularly play video games? How many students or teachers play games on their computer, phone, or mobile device? These screen-based games can be used to pass the time, to avoid doing work or homework, for fun, or while hanging out with friends. Of course, too much screen time can negatively impact your health. But video games can also be educational—and even help improve certain health conditions. This month we will explore how specialized video games are improving the lives of young children with vision problems.

The problem with amblyopia

One of the most common vision problems affecting young children is

amblyopia,

also known as lazy eye. Unlike other eye conditions you might be familiar with such as near-sightedness or far-sightedness, amblyopia cannot be corrected with glasses because it is not the result of problems within the eye. Rather, amblyopia occurs when the eyes and the brain don’t work together effectively. This can be the result of improper eye alignment, as in

strabismus

or crossed eye, or clouded vision caused by

cataracts.

Amblyopia can also occur if one eye is more near-sighted or far-sighted than the other, which is called

anisometropia.

Even if the underlying condition is corrected, amblyopia remains because the brain has become accustomed to using one eye more than the other. Scientists call the disfavored eye the lazy or amblyopic eye, while the stronger eye is known as the fellow eye.

If children with amblyopia are left untreated or unsuccessfully treated by the time they reach elementary school, they may do less well academically. This is because amblyopic children often read more slowly, and slower reading can affect performance on timed tests. It is important for parents and educators to be aware of amblyopia in their students so they can make appropriate accommodations, like extra time for tests. In addition, amblyopia can lead to further vision problems later in life, including reduced vision and blindnes. Treating adults does not produce good results. This is why it is so important to test young children and treat them properly.

Would you rather wear a patch or play a game?

The traditional treatment for amblyopia, known as patching, requires the child to wear a patch over the fellow eye for some number of hours per day. Patching treatment strengthens the lazy eye by forcing the brain to process the visual information it transmits. Although patching is generally effective at first, there are a number of problems associated with the treatment, especially for young children. For example, young children often don’t like the patch, so it can be difficult for parents to get their children to wear it. In addition, between 15 and 50 percent of children treated with patching will relapse after a certain period of time. This may occur because patching does not teach the two eyes to work together to process visual information the way the eyes would in children without amblyopia.

Figure 1. Photo of child wearing a patch

Photo courtesy of the National Eye Institute

To address this problem, researchers including Dr. Krista Kelly and Mr. Reed Jost working in the laboratory of Dr. Eileen Birch at the Retina Foundation of the Southwest in Dallas, Texas partnered with Dr. Robert Hess at McGill University, the medical device company Amblyotech and the gaming company Ubisoft to create a specialized video game called Dig Rush to treat amblyopia. The game strengthens the lazy eye and teaches both eyes to work together.

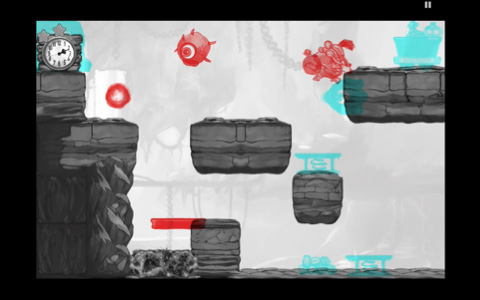

Here’s how it works. Dig Rush features gold miners who must navigate obstacles like fire and monsters to collect enough gold and move up to the next level. Not all objects on the screen are equal, though. The children playing the game wear special glasses that make some elements visible only to the lazy eye, some only to the fellow eye, and some to both eyes together. For example, the miners and monsters appear as very high contrast (i.e., sharp) images, but they are only visible to the lazy eye. Other elements, like gold and fire, are visible only to the fellow eye and are low contrast (i.e., faded or washed out). The amount of contrast in the fellow eye can be increased over time, forcing the two eyes to work more closely together. Finally, background elements are high contrast and seen by both eyes. The game is designed to be effective at strengthening the lazy eye and coordinating eyesight, but also fun and engaging so children will want to play the game.

Figure 2. Screenshot of Dig Rush

Photo courtesy of Ubisoft

Quicker and better results

In order to test the effectiveness of Dig Rush at treating amblyopia compared to the traditional patching method, Dr. Krista Kelly and her colleagues conducted a

clinical trial

with 28 children between the ages of 4 and 10 years. All of the children had been diagnosed with amblyopia by a pediatric ophthalmologist and had worn glasses, if needed, for at least 8 weeks. Half were randomly assigned to be treated with the traditional patching treatment and half with the experimental Dig Rush game. At their initial visit, children in the patching group were provided with a box of disposable eye patches and asked to wear a patch for two hours per day, seven days per week for two weeks, a total of 28 treatment hours. During their initial visit, children in the Dig Rush group were trained how to play the game and given an iPad with the game to take home with them. They were asked to play the game one hour per day, five days per week for two weeks, a total of 10 treatment hours.

Dig Rush treated amblyopia better and more efficiently than the traditional patching method.

Researchers tested the vision of all participants at their initial visit, and again after two weeks. At the two-week visit, every child took the game home for the next two weeks, including those who patched first. The results of the study showed that Dig Rush treated amblyopia better and more efficiently than the traditional patching method. Specifically, the Dig Rush children showed twice the improvement in their vision compared with the patched children at two weeks. This improvement occurred in less than half the required treatment time — hours for Dig Rush compared with 28 hours patching over the same two-week time period. Vision in children who patched caught up to those who had the game since the beginning. “These results are very encouraging,” Dr. Kelly commented. “It seems that Dig Rush can help us improve the vision of many more children affected by amblyopia.”

The researchers report that 39% of the children recovered normal vision in just 4 short weeks, which is very promising. While they did not follow the children after treatment, their lab has shown that the vision improvement with the previous Tetris game was retained for up to 12 months after the treatment ended.

Next steps for amblyopia research at the Retina Foundation of the Southwest include a larger clinical trial that follows more children over a longer period of time and adapting the treatment method used in the game to movies and cartoons that are appropriate for treatment of younger amblyopic children. “The earlier we start treatment,” concludes Dr. Kelly, “the better the outcomes for children.”

Dr. Krista Kelly is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Retina Foundation of the Southwest in Dallas, Texas. She was always interested in science, and she decided to specialize in the development of the visual system due to her own vision problems growing up. When not in the laboratory, Dr. Kelly enjoys dodgeball, camping, and hiking.

Mr. Reed Jost is a Research Associate at the Retina Foundation and has been involved in a number of studies, including new methods of screening for strabismus and amblyopia, and a novel treatment for amblyopia. He received his Master of Science from the University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth, Texas and is an avid golfer.

Dr. Eileen Birch has been the Director of the Pediatric Vision Lab at the Retina Foundation of the Southwest for over 30 years. Her research has led to the discovery that

docosahexaenoic acid (DHA),

a fatty acid found in foods like fish, is important for vision development. Her research has been instrumental in helping children with cataracts and amblyopia see. In her spare time, Dr. Birch enjoys travelling and spending time at her lake house.

Dr. Robert Hess is the Director of the McGill Vision Research Unit at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec. His research has focused on amblyopia and amblyopia treatment for over 30 years.

For More Information:

- Kelly, K., et al. 2016. “Binocular iPad Game vs Patching for Treatment of Amblyopia in Children: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA Ophthalmology, E1-E7

- Li, S., et al. 2014. “A Binocular iPad Treatment for Amblyopic Children.” Eye, 28:1246-53.

- Birch, E. 2013. “Amblyopia and Binocular Vision.” Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 33: 67-84.

To Learn More:

- Retina Foundation of the Southwest.

http://retinafoundation.org/

- Amblyotech.

http://www.amblyotech.com/

- National Eye Institute.

https://nei.nih.gov/health/amblyopia

- American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus.

https://aapos.org/terms/conditions/21

- Vision for Kids.

http://www.visionforkids.org/index.htm

- Prevent Blindness.

http://www.preventblindness.org/amblyopia-lazy-eye

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com