| |

Highlights

Drinking water is important when exercising because it helps with the circulation of blood, temperature regulation, and removal of toxins from the body, among other functions. These researchers measured real-world hiking performance and physiological measures such as heart rate, respiratory rate, body temperature, aerobic capacity (maximal oxygen consumption) and amount of fluid consumed in HOT (estimated average temperature of 105 degrees Fahrenheit) and MODERATE (estimated average temperature of 68 degrees Fahrenheit) environments. The findings indicate that while participants drink more fluid and sweat more in HOT compared to MODERATE temperatures, they still did not bring enough fluid to replace the fluid that was lost about 60% of the time. It felt harder for participants to hike in HOT conditions and participants had reduced athletic performance and aerobic capacity in HOT conditions compared with MODERATE ones. This research indicates the importance of increasing the amount of water you drink when you are engaged in physical activity, especially in hotter environments.

How much water do you drink each day? Water is so important because it helps with the circulation of blood, temperature regulation, and removal of toxins from the body, among other functions. The exact recommendations for daily water intake vary from person to person and depend on factors such as activity level, climate, and gender.

It is commonly recommended that school-age children, adolescents, and adults drink six to eight glasses of water per day. However, studies have shown that more than half of children and adolescents in the United States are not drinking enough water on a daily basis. Even in mild cases, dehydration can impact cognitive functioning and athletic performance.

New research by Dr. Floris Wardenaar, Assistant Professor of Nutrition, and colleagues at the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University’s Tempe and Downtown Phoenix campuses shows that hikers often don’t bring enough water or have a good sense of their water intake needs. This is an important reminder that anyone engaging in physical activity needs to be drinking even more than you think.

Figure 1. Trail sign indicating heat and water needs

[Source: Image courtesy of Dr. Floris Wardenaar]

Dr. Floris Wardenaar is a sports nutritionist who studies how food and beverage consumption affect athletic performance. As a competitive cyclist and nutrition consultant for national teams in his native Netherlands, Dr. Wardenaar has experienced first-hand the difference that food and drink can make.

When he moved to Arizona from the Netherlands, Dr. Wardenaar and his family took up hiking as a new hobby, and Dr. Wardenaar quickly noticed that some hikers came less prepared for excursions than others. In fact, more than 200 rescues occur each year on the iconic Camelback Mountain in Phoenix. One-quarter of these rescues occur because the hikers did not bring enough water.

Dr. Wardenaar decided to combine his passion for hiking and his experience in sports nutrition to better understand water consumption among hikers in the Phoenix area. He created an experiment that would allow him to observe water consumption and its effects on the body among volunteer hikers recruited on the campus of Arizona State University.

To be eligible to participate in the experiment, volunteers needed to spend at least six months of the year in a hot desert climate like Arizona. People who used tobacco, took medication that might interfere with their hydration status, were pregnant, or reported drinking more than 21 alcoholic beverages per week were not eligible to participate.

The experiment included two separate trials to account for changes in climatic conditions. Arizona has a dry desert climate, which means that conditions can change drastically depending on your surroundings. It can feel 10 degrees hotter while hiking on exposed rock than one might have expected at the base of the hike because the sun beats down, there is no shade, and almost no humidity in the air. You can suddenly become overwhelmed with thirst, especially for tourists who may not be used to Arizona weather.

The first hiking day occurred during the summer under HOT conditions, with an estimated average temperature of 105 degrees Fahrenheit (that feels hotter once you start hiking). The second hiking day occurred during the fall under MODERATE conditions, with an estimated average temperature of 68 degrees Fahrenheit.

The hiking experiment took place at Tempe Butte in Tempe, right near the Arizona State University campus. The total hiking distance was about four miles, achieved by climbing Tempe Butte four times. Dr. Wardenaar hypothesized that participants would need to work harder and drink more water (or become more dehydrated) under HOT conditions compared with MODERATE conditions.

Figure 2. Hiking Tempe Butte in Tempe, AZ

[Source: Image courtesy of Dr. Floris Wardenaar]

The day prior to the hike, all participants swallowed a

telemetric capsule

that would allow the researchers to consistently measure

core body temperature

for the duration of the hike. Participants were asked to eat a specific breakfast of cereal with low-fat or soy milk to standardize food intake before the hike. They were also instructed to drink only water between breakfast and the start of the hike and to avoid consuming caffeine.

When participants arrived at the start of the hiking experiment, researchers measured their

metabolic rate,

body weight, core temperature, and heart rate at baseline.

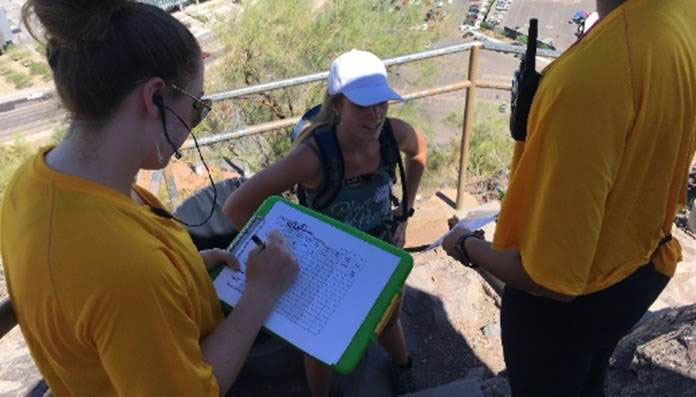

Figure 3. Study participant gets checked in by the research team prior to hiking

[Source: Image courtesy of Dr. Floris Wardenaar]

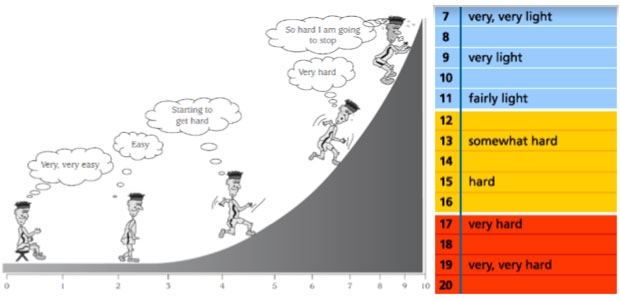

Researchers also asked participants to rank their perceived

exertion

level on a scale of 6 (no exertion) to 20 (maximal exertion), as pictured below.

Figure 4. Eston-Parfitt perceived exertion scale

[Source: Image courtesy of Dr. Floris Wardenaar]

Participants were instructed to bring their own food and as much water as they thought they would need for the duration of the hike, which the researchers also measured. More water, known as rescue water, was available to participants every time they descended Tempe Butte and came back to the research base. If participants ran out of water, they could ask the staff for more. This gave the researchers information about whether participants had brought enough water for themselves and allowed participants to continue with the study. All food and drink brought by participants was weighed before and after the hike to determine how much had been consumed.

Throughout the hike, the researchers measured heart rate, breathing rate, and activity level using a chest strap that participants wore for the duration of the hike. The researchers monitored core temperature using the telemetric capsule the participants had swallowed the night before. Participants were asked to maintain a “brisk” hiking pace without running. Every time the hikers returned to the base of the hike, they were asked to rate their perceived exertion on the same scale shown in Figure 4.

At the end of the hike, researchers measured body weight and participants rated their exertion one final time. Participants provided a first urine sample immediately following the hike and a second urine sample the day after the hike. Urine samples were used to indicate hydration status of each participant.

The first day of hiking in HOT conditions began with twelve participants, seven men and five women. Participants were between the ages of 18 and 40, with an average age of 22 years. Four of the twelve hikers did not finish the total length of the experimental hike that consisted of summiting Tempe Butte four times. Two hikers withdrew after summiting the peak one time, one hiker withdrew after the third time summitting, and one hiker withdrew during the final climb. Three of these hikers did not return to complete the experiment in the fall. A total of nine participants, seven men and two women, completed both hiking trials.

Once both hiking trials had taken place, it was time to analyze the data. Dr. Wardenaar was able to measure athletic performance using the steepness of the climb up Tempe Butte, heart rate, and oxygen consumption. He found that athletic performance was impaired by 11% and aerobic capacity (maximal oxygen consumption) reduced by 7% due to HOT conditions compared with MODERATE conditions. Core temperature was higher in all participants under HOT conditions, as was hiking time. Ratings of perceived exertion were 18% higher under HOT conditions when compared with MODERATE conditions.

In terms of food and beverage intake, water consumption was significantly higher on the HOT day than the MODERATE day. The researchers also noted less urine output on the HOT day. Food consumption was about the same on both days. Seven of the 12 hikers did not bring enough water to maintain their hydration status on the HOT day and four out of nine hikers did not bring enough water to maintain hydration status on the MODERATE day. Despite the rescue water provided by the research team, 10 of 12 hikers on the HOT day and six of nine hikers on the MODERATE day did not drink enough water to make up for sweat loss.

The findings from this initial experiment show that, just as many people don’t drink enough water on a daily basis, many hikers do not correctly anticipate the amount of water they will need while hiking. To further investigate water consumption behavior in hikers, Dr. Wardenaar is planning follow-up studies at trailheads in the greater Phoenix area. At the trailhead, interested participants will have their baseline measurements taken (heart rate, breathing rate, core body temperature, metabolism) and be shown an educational video about hydration needs. Participants will also be offered more water if they decide they want to carry more water than they brought for the hike. “Our goal is to better understand water consumption among hikers in order to support hiker awareness and promote hiker safety,” concluded Dr. Wardenaar.

Dr. Wardenaar also notes that water needs are personal and vary from person to person. “The only way to know how much water you need to be drinking is to monitor your fluid intake and urine output and adjust accordingly. You know that you are well-hydrated when your urine comes out clear or pale yellow.”

Dr. Wardenaar reminds us it is important to increase the amount of water you drink when you are engaged in physical activity or in hotter environments. “Each of us are scientists when it comes to our own bodies,” remarked Dr. Wardenaar. “Make a hypothesis, test it out, see what happens, and learn from it!”

Dr. Floris Wardenaar is an Assistant Professor of Nutrition in the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona. Dr. Wardenaar is a sports nutritionist whose research focuses on how food and beverage consumption impact athletic performance. He is also an avid hiker and biker who enjoys spending time with his family, especially outdoors.

For More Information:

- Linsell, J. et al. 2020. “Hiking Time Trial Performance in the Heat with Real-Time Observation of Heat Strain, Hydration Status and Fluid Intake Behavior.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11). https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/11/4086/htm

- Olzinski, S. et al. 2019. “Hydration Status and Fluid Needs of Division I Female Collegiate Athletes Exercising Indoors and Outdoors.” .? Sports7, 155; doi:10.3390/sports7070155.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6681079/

To Learn More:

Hydration

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/data-statistics/plain-water-the-healthier-choice.html

- TeamUSA.https://www.teamusa.org/USA-Triathlon/News/Blogs/Youth-Tips/2018/April/24/How-Much-Water-Do-Youth-Athletes-Need

- The Sports Institute.https://thesportsinstitute.com/hydration-in-the-heat-for-young-athletes/

Hiking Preparedness

- American Hiking Society.https://americanhiking.org/resources/10essentials/

- National Park Service.https://www.nps.gov/articles/hiking-safety.htm

Sports Medicine

- Sports Medicine Today.https://www.sportsmedtoday.com/

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |

|

|

Dr. Floris and his research team at the base of Tempe Butte. Research team members from left to right:

Row 1 (back): Dr. Floris Wardenaar, Darya Youssefi, Katie Pesek, Simran Bakta, Jay Chan, Rebecca Mrotek.

Row 2 (front): Maryam Nalbandian, Kayla Boeckman, Emily Pelham, Josh Linsell. [Source: Image courtesy of Dr. Floris Wardenaar]

https://www.abc15.com/news/region-southeast-valley/tempe/arizona-state-university-studying-effects-of-heat-on-athletic-performance

Sign Up for our Monthly Announcement!

...or  subscribe to all of our stories! subscribe to all of our stories!

What A Year! is a project of the Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research.

|

|