Not all exercise is created equal. Walking does not have the same effects on your body as running, which in turn, is different from lifting weights. We know this intuitively based on the effects of exercise on heart rate, breathing rate, and muscle burn. On a physiological level, types of exercise fundamentally differ in how they make the body use energy. There are two broad classes of exercise based on cellular metabolism:

aerobic

and

anaerobic.

You may have heard the term "aerobic" used to indicate a certain level of ongoing exercise intensity. On a cellular level, aerobic exercise depends on oxygen to transfer energy from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. This is why aerobic exercise is often characterized by an elevated breathing rate and increased depth of breathing—to help increase oxygen intake. The heart responds by increasing heart rate and the heart's strength of contraction—to help deliver blood and the oxygen it carries to your tissues more quickly.

At some point, though, exercise intensity increases to the extent that there is not enough oxygen for your tissues to use. Without sufficient oxygen, cells must rely upon energy stored in the bonds of sugar molecules in cells and transform that into useable energy, when needed, without oxygen. The metabolic pathway responsible for this energy transfer that takes place without oxygen is known as anaerobic metabolism. Physical activity that causes cells to revert to anaerobic metabolic pathways is known as anaerobic exercise. This month we will highlight the work of researchers at Simon Fraser University in Canada who hope to better understand the connections between aerobic and anaerobic exercise, and what those links might mean for exercise performance in mountain ultra-marathons.

Mountain Ultra-Marathons

Michael Rogers was always interested in athletics and exercise. This passion turned into a career as a certified personal trainer where he helped clients attain their fitness and athletic goals. As a personal trainer, Michael was asked all sorts of questions about how and why the body works the way it does. Fascinated by his clients' questions, Michael decided to pursue a master's degree in biomedical

physiology

and

kinesiology

in order to find some answers.

As a graduate student, Michael, under the supervision of Dr. Matthew White at Simon Fraser University, turned his attention to high-performance athletes who participate in what are known as mountain ultra-marathons (marathons longer than the traditional marathon of 26 miles, 385 yards that was run by Philippides in 490 BC, from the Battle of Marathon to Athens to give news of the victory).

Figure 1. View from the top of the first climb of the race

Mountain ultra-marathons are distinguished from other types of marathons by four factors: distance, elevation, environment, and technique. These races are typically at least 50 kilometers (30 miles) long and involve a significant amount of elevation gain and loss. For example, the mountain ultra-marathon called the Knee Knackering North Shore Trail Run features three mountains that participants must go up and over. Changes in temperature and uneven terrain provide additional challenges. The average time for completion of this Knee Knackering North Shore Trail Run, a mountain ultra-marathon is 7-8 hours.

It was evident to Dr. White, Michael, and other members of the White laboratory that all the participants in the mountain ultra-marathon exhibited extraordinary levels of aerobic fitness. Yet some runners performed much better than others on race day. To understand why, Michael examined another key factor of high-intensity exercise: anaerobic metabolic capacity. Michael hypothesized that, given the similarities in aerobic performance amongst mountain ultra-marathon participants, additional factors like anaerobic metabolism might become more critical for distinguishing between the fastest and slowest times.

Time to Experiment

To test this hypothesis, Michael, along with other members of the White lab, recruited ten healthy male athletes who were going to participate in the mountain ultra-marathon. The athletes were identified during training runs and all had agreed to participate in the study on race day and during laboratory sessions. The average age of participants was 47 years.

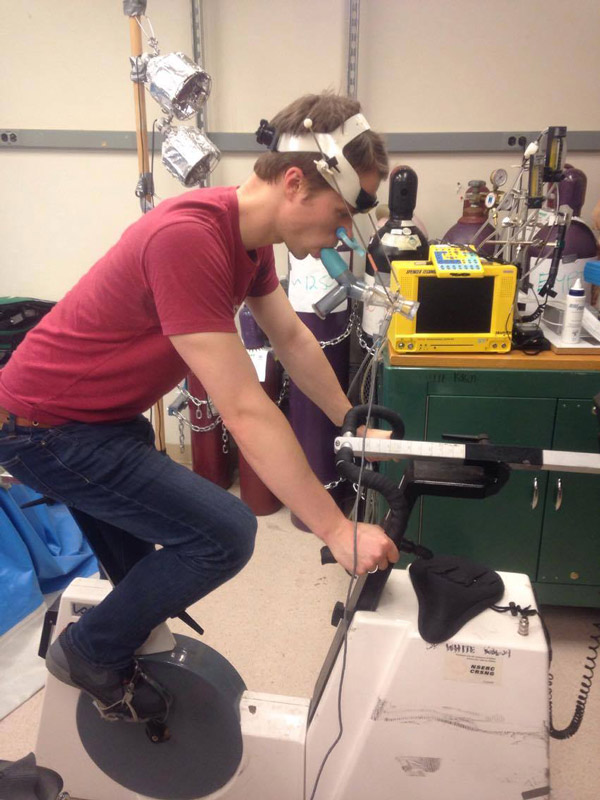

Figure 2. Michael Rogers participating in the Wingate anaerobic test in the laboratory

Before or after race day, all participants came to the laboratory on two occasions, once to measure aerobic capacity, indicated by maximum oxygen consumption, and once to measure anaerobic capacity, indicated by maximum power output. Aerobic capacity was measured on a treadmill exercise in which participants were instructed to run as fast as possible for as long as possible. Anaerobic capacity, on the other hand, was measured by a minute-long test on a stationary bicycle. The participants warmed up for the first thirty seconds before pedaling at maximum power for thirty seconds against high resistance. Michael took an average of the power output observed during the thirty seconds of maximum power and controlled for body weight to get a measure of anaerobic metabolic capacity that could be used for comparison.

In the final stage of the experiment, Michael and his colleagues arrived early on race day to equip participants with heart and GPS monitors. Heart rate was recorded for the duration of the race and participants were ranked according to finishing speed.

Figure 3. Heart rate and GPS monitor

Back in the laboratory, it was time to analyze the data. Michael wanted to know which of the aerobic and anaerobic measures they had gathered best predicted the outcome of the race. For these elite runners, all with high aerobic capacities, their anaerobic capacity, as measured on a stationary bicycle in the laboratory, was the best predictor of athletic success in the 50 km mountain ultra-marathon. Indeed, data recorded by heart monitors on race day showed heart rates well above the threshold at which anaerobic metabolism usually kicks in, helping to confirm this analysis.

Michael is quick to emphasize that this study does not discount the significance of aerobic fitness and each of his participants already had a high aerobic capacity. Indeed, aerobic capacity is very important for the success in any endurance event. Rather, it indicates the potential importance of anaerobic fitness, which is not often considered as a major factor in ultramarathon athletic performance. Based on these findings, Michael recommends including anaerobic fitness training into your regular aerobic exercise training.

In future experiments, Michael is planning to conduct a study that compares the performance of mountain ultra-marathoners who have received additional anaerobic training to those who have not. The results of this study may provide insight into the importance of anaerobic training—or not. "I'm very excited to continue this research," Michael comments.

Michael Rogers is a Master's student at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada, working on a project to identify the role of anaerobic fitness in the performance of ultramarathon runners. When not studying or researching, Michael continues to work as a certified personal trainer and participates in a variety of activities on campus including the personal training club and Korean culture club at SFU. His supervisor is Dr. Matthew White, Associate Professor of Biomedical Physiology and Kinesiology at Simon Fraser University.

For More Information:

- Press release from Experimental Biology 2016: http://www.the-aps.org/mm/hp/Audiences/Public-Press/2016/12.html

To Learn More:

Mountain Ultra-Marathons

- Do more uphill sprints! Higher anaerobic fitness gives edge to mountain ultra-marathon runners.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160403200401.htm

- Knee Knackering North Shore Trail Run website.

http://www.kneeknacker.com/

- Dr. Matthew White lab.

https://www.sfu.ca/bpk/people/faculty_directory/white.html

Exercise and Physical Fitness

- American College of Sports Medicine Fit Society.

http://www.acsm.org/public-information/fit

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com