| |

Highlights

Teeth can tell researchers clues about our lives. These researchers hypothesized that stressful moments in one’s life might leave behind a record in the teeth, such as through stress lines in the teeth enamel or changes in enamel density, enamel volume, and pulp volume.

Several experiments were conducted to investigate this hypothesis. Results of one analysis showed the width of the neonatal line (a major stress line occurring around the time of birth) in baby teeth can indicate stressful experiences of the mother during pregnancy. A second analysis showed that enamel density and enamel volume were correlated with reported mental health symptoms.

In ongoing follow-up experiments, these researchers are studying the teeth of children who were in utero or recently born in April 2013 in Boston to see if the stress of the Boston Marathon Bombing can be found in their teeth.

February is National Children’s Dental Health Month, a month dedicated to raising awareness about the importance of children’s oral health. This year’s theme is “Brush, Floss, Smile.”

Figure 1. The theme of National Children’s Dental Health Month 2023 is “Brush, Floss, Smile.”

[Source: https://www.ada.org/resources/community-initiatives/national-childrens-dental-health-month]

Did you know that your teeth are the strongest part of your body? Teeth are so strong, in fact, that they last long after the rest of our bodies have decomposed. This is why

anthropologists,

archaeologists,

and other researchers who specialize in learning about our ancestors often turn to teeth for clues. Teeth can show the approximate age of a person. They can also tell us a lot about an ancient person’s diet and life circumstances. New research by Dr. Erin Dunn, Dr. Rebecca Mountain, and colleagues shows that baby teeth can reveal clues about a mother’s life experiences during pregnancy and possibly indicate risk factors for a child’s future mental health outcomes.

The Life of Teeth

Although most babies are born without erupted teeth visible in the mouth, tooth development actually begins during pregnancy.

Primary teeth,

commonly known as baby teeth, start to form around six weeks of

gestational age,

and

permanent teeth

begin to develop at about 20 weeks of gestational age. Both baby and permanent teeth typically remain under the gums until after a child is born.

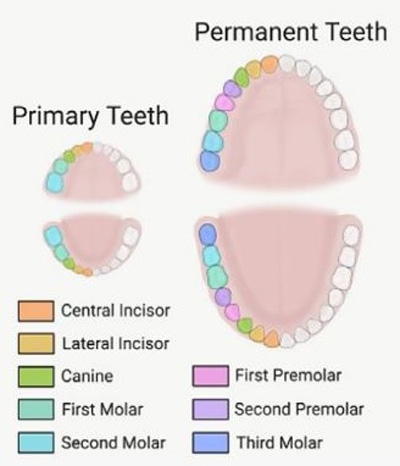

Baby teeth usually erupt, or become visible above the gum line, between 6 to 12 months of age. Most children have a total of 20 baby teeth, 10 on the upper jaw and 10 on the lower jaw. At around six years of age, baby teeth will start to fall out and be replaced by permanent teeth. Adults typically have 32 teeth, 16 on the upper jaw and 16 on the lower jaw.

As you can see in your own mouth, not all teeth are alike.

Figure 2. Types of teeth in children (primary teeth) and adults (permanent teeth).

[Source: Davis et al. 2020, Figure 1d]

There are four different types of human teeth that serve different functions and are located in different parts of the mouth.

- Incisors: A set of permanent teeth has eight total incisors, four on top and four on the bottom. These are the smaller front teeth that help you bite into food. Incisors are typically the first baby teeth to appear.

- Canines: A set of permanent teeth has four total canines, one on each side of the four incisors, two on the top and two on the bottom. These are the long pointy teeth that are good for tearing food apart. They usually emerge after the incisors, between the ages of 16 and 20 months.

- Premolars: A set of permanent teeth has eight total premolars, two next to each canine. These teeth have a flat surface that is good for grinding smaller pieces of food.

- Molars: A set of permanent teeth has 12 total molars, three next to the premolars. These are the largest, strongest teeth used to grind food into small pieces to swallow. Molars are further subdivided based on when they emerge in the mouth. Four molars come in around age six (first molars), four molars come in around age 12 (second molars), and the final molars (third molars or wisdom teeth), come in in the later teenage years and sometimes not at all.

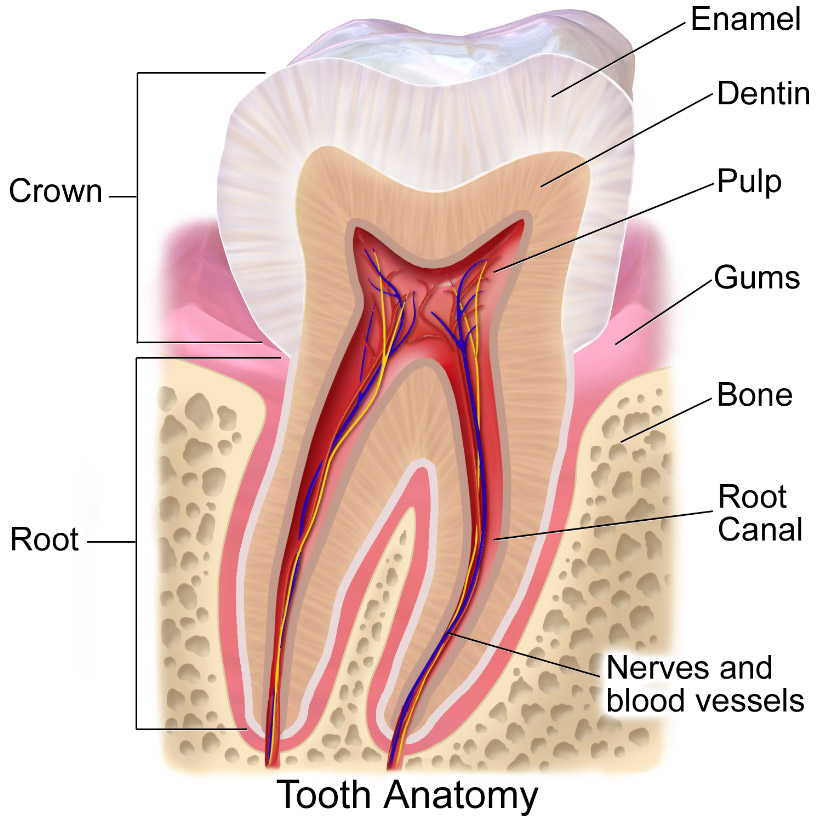

Each of our teeth consists of four parts. The innermost part of the tooth is the root, which connects the tooth to the jaw. The pulp is the soft inside of the tooth that contains nerves and blood vessels. Dentin is the layer that surrounds the pulp and is the main part of the tooth. The dentin is surrounded by enamel, which is the outer layer of the tooth. Enamel is the hardest substance in the human body. This is the white part of your teeth that you brush (ideally twice a day!).

Figure 3. Anatomy of the human tooth.

[Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tooth_enamel]

Since enamel can last for hundreds or thousands of years, sometimes teeth are the only remains of ancient life that archaeologists can find.

Figure 4. Remains of ancient human teeth.

[Source: Prof. Israel Hershkovitz, Tel Aviv University. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fossil_Qesem_teeth.jpg]

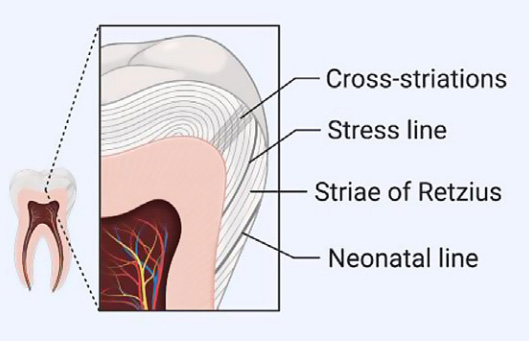

Teeth can provide a wealth of information because of the unique way they are formed. Teeth develop in incremental layers, with enamel layers being deposited consistently on a daily, and weekly basis, leaving behind growth lines. Does that sound familiar? These growth lines are similar to the rings of a tree that mark its age.

Just as one can look at the size of the rings on a tree to identify years of more growth or less, the width or color of growth lines in tooth enamel can also indicate times of stress. Researchers have found that thicker or darker growth lines in teeth, often called “stress lines”, can be indicators of dietary stress or scarcity in the food supply. One of the most prominent growth lines in baby teeth is called the neonatal line, which forms right around the time of birth. The neonatal line can be used to differentiate between the parts of the tooth that formed during pregnancy from the parts of the tooth formed after birth. Previous studies have shown that a thicker neonatal line could indicate increased stress right around the time of birth.

Figure 5. Layers of enamel including neonatal line.

[Source: Davis et al. 2020, Figure 1c]

Although researchers who study past human populations use teeth as indicators of experiences that have already happened, Dr. Dunn, Dr. Mountain, and colleagues wanted to know whether teeth could also be used to predict future risk of mental health disorders. They hypothesized that evidence of stressful or traumatic childhood experiences, a major risk factor for mental health issues, might be found in the layers of teeth enamel.

The Predictive Possibilities of Teeth

Dr. Erin Dunn’s research focuses on early childhood experiences and how they can impact future mental health outcomes. In particular, Dr. Dunn is interested in the timing of these early childhood experiences and finding specific time windows in which they are most impactful. However, much of the research in this field has relied on the memories of individuals and their parents to recall traumatic events and the specific time periods when these events occurred. These methods are not ideal because they rely on memory, which can often be inaccurate, and they can require participants to revisit events they might prefer not to remember. In addition, researchers do not have a way to measure the level of stress of a particular event that happened in the past.

Given the challenges of memory-based methodology, Dr. Dunn was looking for more objective measures of early childhood experiences. She aims to develop interventions for mental health disorders early in life before symptoms even emerge or become severe. She was excited to learn that anthropologists and archaeologists use adult permanent teeth as sources of information about ancient peoples and wondered whether baby teeth might also reveal information about a child’s formative years.

Dr. Rebecca Mountain learned that Dr. Dunn was planning research into early life stress and baby teeth and was eager to join the project as a postdoctoral research fellow in Dr. Dunn’s laboratory. Dr. Mountain had completed her Ph.D. in archaeology where her research focused on how stress affects bone loss in past populations. She was excited to use her expertise to consider how stress could affect teeth and bone development in living populations. Together, Dr. Dunn, Dr. Mountain, and colleagues designed an experiment to test the hypothesis that baby teeth could provide clues about the future mental health of a child.

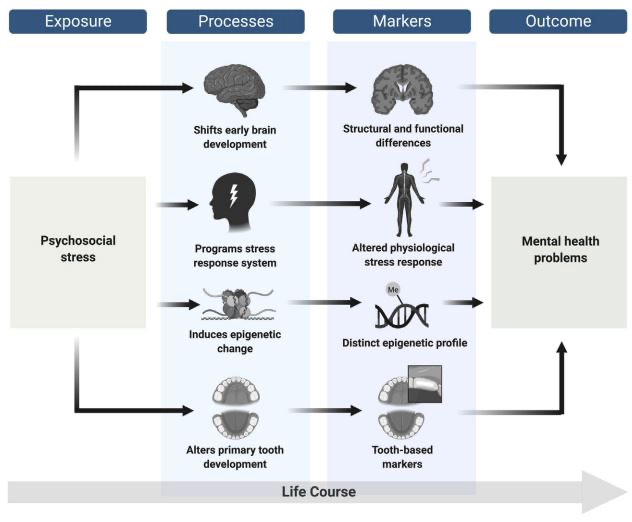

In a project led by Kathryn Davis, a former research coordinator in Dr. Dunn’s lab and current Ph.D. student at Boston University, these researchers developed a conceptual model to lay out their hypotheses for how teeth might be used as

biomarkers

for past experiences and future mental health outcomes. The model is called the Teeth Encoding Experiences and Transforming Health model, or TEETH for short.

Figure 6. Teeth Encoding Experiences and Transforming Health conceptual model.

[Source: Davis et al. 2020, Figure 2]

The model has since been supported by data analyses from two longitudinal studies: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children and the Peers and Wellness Study.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) in the United Kingdom recruited pregnant mothers with delivery dates between April 1, 1991 and December 31, 1992. A total of 14,541 pregnant mothers were enrolled during this time period. The study was later extended so the total cohort includes 14,901 children and their mothers.

In addition to many other variables, the ALSPAC study included four measures of lifetime experiences of the mother: stressful life events, medical history, neighborhood satisfaction, and social support.

- Stressful life events: The researchers asked about stressful events that occurred during pregnancy including the death of a partner, the death of a child, or the death of a friend or relative. Mothers were asked about these life events at 18 weeks of pregnancy and at eight weeks after birth.

- Medical History: When mothers were 12 weeks pregnant, they were asked about 24 medical and psychiatric conditions they might have experienced over the course of their lives. Drs. Dunn and Mountain were interested in the responses to the question about whether the mother had ever experienced severe

depression

or any psychological problems.

- Neighborhood satisfaction: When mothers were eight weeks pregnant, they filled out questionnaires about the safety and cleanliness of their neighborhood.

- Social support: Mothers were asked about their levels of social support when they were 12 weeks pregnant and eight weeks after delivery.

In addition to the questionnaires, the mothers were also asked to provide samples of baby teeth that had fallen out of their children’s mouths. ALSPAC collected a total of 4,168 baby teeth from children ages 5 to 7 years. Most of these teeth were smaller incisors, which can be hard to analyze. For this study, Drs. Dunn, Mountain, and colleagues used 70 larger canine teeth from 70 children participants in ALSPAC.

Drs. Dunn and Mountain, as well as colleagues Yiwen Zhu, a former data analyst in Dr. Dunn’s lab and current Ph.D. student at Harvard University, and Dr. Felicitas Bidlack from the Forsyth Institute, hypothesized that the teeth of children whose mothers had reported stressful life events during pregnancy would have thicker neonatal lines. The results showed thicker neonatal lines in children born to mothers who reported having experienced depression or psychiatric problems in the past or who experienced depression or anxiety when they were 32 weeks pregnant compared to children whose mothers were not exposed to these stressors.

In addition, children whose mothers reported increased social support had thinner neonatal lines, indicating that social support, known to be a protective factor against depression, may be helpful in offsetting some of the negative impacts of stressful events. Overall, these findings support the researchers’ hypothesis that the neonatal line of baby teeth can indicate stressful experiences of the mother during pregnancy.

The Peers and Wellness Study

The Peers and Wellness Study (PAWS) is a longitudinal study of school-aged children in California public schools. The purpose of the study was to better understand how family environment, social environment, and biological responses impact the physical and mental health of children. The initial study included 338 kindergarteners ages five and six years who participated from 2003-2005 in the San Francisco Bay area.

Participants completed a variety of tasks including emotional and cognitive challenges as directed by the researchers. Before, during, and after the tasks, the researchers measured breathing rate and cortisol levels, among other physiological measurements. In addition, participants and their parents were asked to complete questionnaires to assess mental health symptoms. Parents filled out the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire, which asks about the child’s physical health, recreational activities, social experiences, and behavior. Children completed the Berkeley Puppet Interview, which uses puppets to ask about a child’s experiences and preferences.

|

Iggy: I have lots of friends.

Ziggy: I don't have lots of friends.

Iggy: How about you? |

|

Ziggy: My parents' fights are about me.

Iggy: My parents' fights are not about me.

Ziggy: How about your parents? |

Figure 7. Examples of the Berkeley Puppet Interview with puppets Iggy and Ziggy interacting with a child.

[Source: https://dslab.uoregon.edu/about/berkeley-puppet-interview/]

From 2004 to 2006, a dental study was added to PAWS. This study collected baby teeth donated by a subset of participants who had lost a tooth during the nine months of their first grade school year. The donated teeth were all incisors, which are usually the first teeth to fall out. All donated teeth included in the study did not have any cavities or any other major deformities.

Drs. Dunn, Mountain, and colleagues used a three-dimensional imaging approach called

micro-CT

that uses x-rays to visualize and analyze the teeth. Measurements included enamel density and enamel volume. They performed statistical analyses to determine whether these tooth measures were correlated with any mental health symptoms reported in the questionnaires.

The results showed that lower enamel volume was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms, whereas higher enamel density was associated with higher levels of these symptoms. These results provide additional support for the TEETH conceptual model, and the researchers hope that future studies will expand these findings.

Ongoing and Future Work

Results from data analyses of both the ALSPAC and PAWS studies demonstrate the potential for baby teeth to be used as biomarkers in future studies. In order to continue this research, Dr. Dunn is currently leading a study called Stories Teeth Record of Newborn Growth (STRONG). For this study, Dr. Dunn recruited women who were pregnant or had children up to one year of age at the time of the Boston Marathon Bombing on April 15, 2013.

The Boston Marathon Bombing was an attack that took place on the day of the Boston Marathon in 2013 in Boston, MA. The perpetrators who planted the bombs were not captured for several days after the event, and residents of some Boston area neighborhoods were asked to stay indoors until they were captured. “This was a very stressful time for those of us living in Boston,” explained Dr. Dunn. “We want to know whether we can see evidence of that stress in the teeth of children who were in utero or born around that time.”

The researchers have finished enrollment of over 250 women in the study. Participants send the researchers baby teeth their children have lost. When the researchers receive a tooth, they send the child badges and a book called “The Science Tooth Fairy” that explains the purpose of the research. “We are excited to start analyzing the data and see what the results show,” concluded Dr. Dunn.

Dr. Erin Dunn is Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Associate Investigator in the Center for Genomic Medicine at Mass General Research Institute. Her research focuses on how early childhood events can influence mental health outcomes later in life. Children and families know her as the Science Tooth Fairy. When not in the laboratory, Dr. Dunn enjoys running, reading, and trying new restaurants. If you have questions or want to learn more about her research, you can email her at edunn2@mgh.harvard.edu.

Dr. Rebecca Mountain is currently a postdoctoral research fellow in the laboratory of Dr. Katherine Motyl at the MaineHealth Institute for Research. Her research examines how psychological stress, such as social isolation and loneliness, affects bone development and risk for osteoporosis. Previously, Dr. Mountain completed a postdoctoral research fellowship in the laboratory of Dr. Erin Dunn, where she participated in the research project described here. When not in the laboratory, Dr. Mountain enjoys gardening, hiking, making quilts, drawing, and baking, among other hobbies.

For More Information:

- Dunn, E. et al. 2022. “Association Between Measures Derived From Children’s Primary Exfoliated Teeth and Psychopathology Symptoms: Results From a Community-Based Study.” Frontiers in Dental Medicine, Vol 3, Article 803364. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdmed.2022.803364/full

- Mountain, R. et al. 2021. “Association of Maternal Stress and Social Support During Pregnancy With Growth Marks in Children’s Primary Tooth Enamel.” JAMA Network Open, 4(11). https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2785880

- Davis, K. et al. 2020. “Teeth as Potential New Tools to Measure Early-Life Adversity and Subsequent Mental Health Risk: An Interdisciplinary Review and Conceptual Model.” Biological Psychiatry, 87(6): 502-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31858984/

To Learn More:

- Dunn Lab. https://www.thedunnlab.com/

- The Stories Teeth Record of Newborn Growth (STRONG) Study. https://rally.massgeneralbrigham.org/study/strong

- Lazar, K. “The tooth fairy is calling: Boston researchers seeking baby teeth for health study.” Boston Globe, 7 Mar. 2022. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/03/07/metro/tooth-fairy-is-calling-boston-researchers-seeking-baby-teeth-health-study/

- Gower, T. “Baby teeth may be window to child’s risk of mental health disorders.” Harvard Gazette, 9 Nov. 2021. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2021/11/baby-teeth-may-help-identify-kids-at-risk-for-mental-disorders/?utm_source=SilverpopMailing&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Daily%20Gazette%2020211110

- Lazar, K. “Can kids’ teeth reveal emotional trauma? A new study suggests yes.” 17 Dec. 2019. https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2019/12/17/science-tooth-fairy-proposes-screening-children-teeth-for-hints-future-mental-health-problems/vqtIOh9345B9R8iGYOBYlO/story.html?event=event12

- Mouth Healthy, from the American Dental Association. https://www.mouthhealthy.org/

- Your Child’s Teeth. https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(18)30788-8/fulltext

- Your Children’s Teeth. Education and Resources for Parents. https://www.mychildrensteeth.org/resources-for-parents/

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |

|

|

Dr. Rebecca Mountain

Dr. Erin Dunn

Members of Dr. Dunn’s laboratory: Top row left to right: Madison Bigler, Nitasha Siddique, Mona Le Luyer, Alexandre Lussier Bottom row left to right: Alison Hoffnagle, Samantha Stoll, Erin Dunn, Simone Lussier, Grace Burke

Sign Up for our Monthly Announcement!

...or  subscribe to all of our stories! subscribe to all of our stories!

What A Year! is a project of the Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research.

|

|