|

Have you ever heard of Leonardo da Vinci? If not, perhaps you've heard of the Mona Lisa? It's one of his most famous works. Indeed, Leonardo da Vinci painted and sculpted himself a prominent place in history during his lifetime in Renaissance Italy, in the mid-fifteenth to mid-sixteenth centuries. But did you know that da Vinci was also a scientist and inventor? That's right!

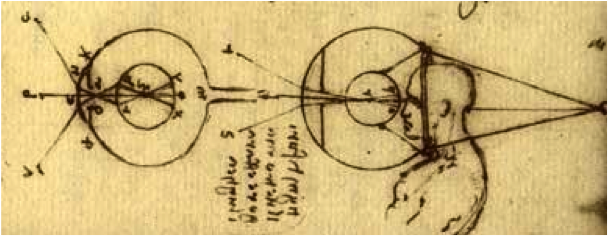

Leonardo da Vinci is widely credited with developing the first idea for a contact lens in the early 1500's, a device placed into the eye that would correct vision much like

modern contact lenses.

Fig. 1 - da Vinci drawings of the eye

http://www.zhax.net/twc/contactLens.html

At the time, da Vinci was more interested in changing perspectives for his artistic endeavors, but the contact lens idea was taken up time and again until German scientists created the first modern lens in the late 1800's. Today over 30 million Americans use contact lenses on a regular basis, according to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Recently, researchers have been developing uses for contact lenses that do more than just correct vision: they treat diseases of the eye and improve outcomes after eye surgery. This month, we'll learn about these lenses of the future.

Dr. Joseph Ciolino, an

ophthalmologist

at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, and his mentor Dr. Daniel S. Kohane, director of the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery at Boston Children's Hospital, are developing a contact lens that can release drugs to treat eye problems. "Researchers have been trying for years to develop contact lenses for drug delivery," explains Dr. Kohane. "We thought we could make it work." The key concept was to develop a contact lens that would release a useful amount of drug at a constant rate for days to weeks.

The key concept was to develop a contact lens that would release a useful amount of drug at a constant rate for days to weeks.

"We wanted to develop a better treatment for eye patients that would increase

compliance

and be more effective," comments Dr. Ciolino. He sees lots of patients with eye problems. This means that he prescribes many kinds of eye drops on a daily basis.

Approximately 90 percent of all eye medications are given as eye drops.

"Right now, eye drops are the most effective treatment we have for many patients," explains Dr. Ciolino.

But eye drops may not be the most ideal method for medication delivery. Even applied exactly as prescribed, eye drops are inefficient. Only about one to seven percent of the medication is actually absorbed by the eye.

The rest of the medication is diluted by tears and blinking.

And that's if everything is done correctly, which is not necessarily the case. Although putting in eye drops once or twice a day sounds manageable, imagine if you had to put them in three or four times a day. What if they had to be put in every hour, to reduce inflammation after recovering from eye surgery? What if once a day you had to put in several different types of eye drops at a time? "The biggest problem with these treatable conditions is

non-compliance,"

remarks Dr. Ciolino. "Patients aren't following the doctor's orders."

If you have a minor condition such as

dry eye

and forget to put your eye drops in, it's not a big deal. But much more serious conditions are treated with eye drops, as well, and forgetting can be really bad.

Glaucoma

is a good example. Glaucoma is an eye condition in which eye pressure increases, putting increased pressure against the

optic nerve.

There are several reasons this can happen. The most common is poor fluid circulation in the front of the eye. If the condition goes untreated, it can result in permanent loss of vision. Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of blindness worldwide, according to the

World Health Organization.

Although older people are generally at greater risk for developing glaucoma, it can develop at any age. The Glaucoma Research Foundation estimates that about

one in every ten thousand babies in the U.S. is born with glaucoma.

There is no cure for glaucoma, but early detection and treatment can prevent vision loss in many cases. "That's why it's so important to go to your eye doctor for regular check-ups," adds Dr. Ciolino. In severe cases, surgery may be necessary, but the first line of treatment is always eye drops. After surgery, eye drops will still be necessary to control eye pressure.

Contact lenses for drug delivery present particular challenges for researchers. First, they can't interfere with the patient's vision. Second, the medication in the contact lens needs to be delivered slowly over a long time at a constant rate. A standard contact lens can absorb some drug and release it, but unfortunately it releases the medication very quickly. "Most diseases, though, would be better treated by smaller doses of medication at timed intervals," explains Dr. Ciolino. "We had our work cut out for us."

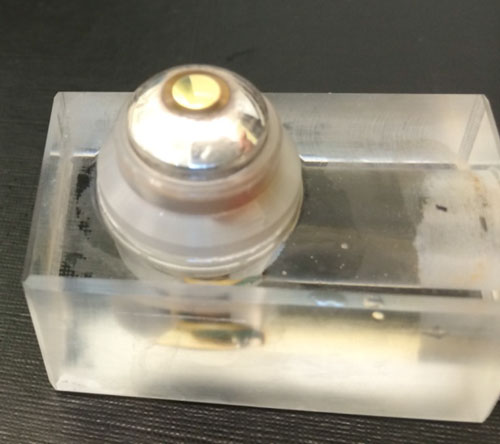

Drs. Kohane and Ciolino developed a sandwich-like design for the contact lens. On the inside is the medication attached to a polymer; the one they have used so far is called polylactic-co-glycolic-acid or PLGA. PLGA only lets out a certain amount of medication at a time. The thicker the layer of PLGA, the more slowly the medicine will leak out into the eye; less medication results in slower release of the medication. This is how the researchers are able to control the rate of drug delivery. The drug-polymer films were then surrounded by a clear gel called methafilcon that is commonly used to make contact lenses.

Fig. 2 - The drug-eluting contact lens.

To test their design, Dr. Ciolino and Dr. Kohane first placed the medicated contact lens in fluid that mimics the fluid that bathes the eye. They tested their design using

ciprofloxacin,

a common topical

antibiotic.

They changed the solution every day and measured the amount of medication that had leaked into the fluid. The research team refined the design of the contact lens several times using the information obtained from their experiments.

Fig. 3 - The contact lens on a device that measures oxygen permeability.

To test whether the medication was effective, Dr. Kohane and Dr. Ciolino introduced the bacteria

Staphylococcus aureus

into the fluid. You may know S. aureus as the cause of many bacterial infections including

boils,

pneumonia,

some types of

food poisoning

and eye infections. Eye infections caused by S. aureus can be treated with ciprofloxacin, applied in the form of eye drops. If the medicated contact lens containing ciprofloxacin was effective, the researchers hypothesized that the S. aureus bacteria in the fluid would be killed. This is exactly what happened. "These results showed that our design was effective in the laboratory," explained Dr. Kohane.

When the design seemed correct, they were able to apply the contact lenses to the eyes of rabbits, which are commonly used to test contact lenses. Using this method, Drs. Ciolino and Kohane optimized the rate of drug delivery, and the lens can now release a steady stream of drug for thirty days.

Building on this model, Drs. Ciolino and Kohane have now shown that they can also deliver

latanoprost,

a common drug to treat glaucoma, in the same way. "We now know that our contact lens can deliver a steady stream of glaucoma medication for thirty days," concludes Dr. Kohane. "The next step is to determine whether the medication is effective at treating eye disease."

The contact lenses could also be used in animals with eye conditions, to improve veterinary care.

Drs. Ciolino and Kohane believe their medicated contact lens could be a platform to deliver many different types of drugs. "Glaucoma,

corneal ulcers,

eye infections, all of these conditions that we now treat with eye drops could benefit from these contact lenses," explains Dr. Ciolino. "Not to mention patients recovering from eye surgery." The contact lenses could also be used in animals with eye conditions to improve veterinary care.

Dr. Joseph Ciolino is an ophthalmologist at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston, MA specializing in diseases of the cornea. He regularly sees patients, in addition to his time in the laboratory developing medicated contact lenses with Dr. Kohane. He says of Dr. Kohane: "Dan was an excellent mentor in my life. It's always good to have a good mentor." When not in the laboratory or the clinic, Dr. Ciolino enjoys hiking, skiing and spending time with his family.

Dr. Daniel Kohane is a pediatric intensive care doctor and anesthesiologist and is Professor of Anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, a Senior Associate in Pediatric Critical Care and Director of the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery at Boston Children's Hospital. His research focuses on improving drug delivery systems for a variety of conditions. Together with Dr. Ciolino, he has developed a new model for a medicated contact lens. Dr. Kohane was mentored by Dr. Robert Langer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, MA, who he describes as "the guru of drug delivery and biomaterials." When not in the laboratory or the clinic, Dr. Kohane enjoys spending time with his family. His hobbies include martial arts and reading Greek and Roman classics.

To Learn More:

- Ciolino, J. et al. 2014. "In vivo performance of a drug-eluting contact lens to treat glaucoma for a month." Biomaterials, 35(1): 432-9

- Ciolino, J. et al. 2009. "A drug-eluting contact lens." Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 50(7): 3346-52.

For More Information:

- Kohane Laboratory: http://aneswebout.tch.harvard.edu/sites/kohane/

Glaucoma

- National Eye Institute. http://nei.nih.gov/glaucoma

- Glaucoma Research Foundation. http://www.glaucoma.org/glaucoma

- The Glaucoma Foundation. http://www.glaucomafoundation.org

Other Eye Diseases

- Laser Eye Surgery Hub. https://www.lasereyesurgeryhub.co.uk/

- World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/blindness/causes/priority/en

Written by Rebecca Kranz with Andrea Gwosdow, PhD at www.gwosdow.com

HOME | ABOUT | ARCHIVES | TEACHERS | LINKS | CONTACT

All content on this site is © Massachusetts

Society for Medical Research or others. Please read our copyright

statement — it is important. |